Clinical Reasoning, as a means to an end, for the development of Self Actualisation as a primary care Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist

by Martin Krause (1999-2008)

The science of navigation can be taught, the art of navigation needs to be learnt through experience.

Art is about the experience of questioning conventional paradigms.

The conundrum for health professions is that 'statistically' we work within a 95% confidence interval. Hence, when working with human bodies we are invariably working on the edge of the unknown. By using a structured reasoning approach we can eliminate variables from a list of probabilities, eventually defining the essence of the clinical picture. Hereby the umbrella diagnosis which incorporates everything but means nothing (eg Non-specific low back pain) is eliminated.

These pages present a structure and a process to the art of learning clinical reasoning. It will encourage the reader to interpret all findings, be curious of why some things work and others don't, and why some things work most of the time but not all of the time. It will also endeavor to provide a navigational chart of learning whereby the clinician can excel whilst standing on the shoulders of clinical research giants.

Experts don't store answers, rather they store key facts and strategies which help them gain those answers. Hereby, they use long term memory that has taken at least 10 years (10000 hours) of concentrated effort using metacognitive and reflective thinking strategies. Experts tend to recruit larger areas of the brain for information processing thereby increasing their RAM capacity. Neurons that fire together, wire together. This leaves the short term memory free for processing novel stimuli.

Expert opinion lies on the lowest rung of the Evidence Based Practice (EBP) hierarchy. However, the process of Practice Based Evidence (PBE) should form an integral part of every treatment strategy and hereby provide a catalyst for EBP. One form of consensus decision making is the Delphi approach whereby several experts are asked an opinion about a presentation. During a second round, the experts are shown all other opinions and then asked to rank those opinions. The objective is to use several rounds of questions and answers to narrow down the opinions to those which are most likely or more probably. The following is a summary of the processes needed clinically to develop ones clinical opinion expertise and how interaction with the client and other professions can lead to an optimised management strategy and hence treatment outcome. Hereby, Dogma is reduced and many avenues of thought are accommodated.

"fish live in the sea, therefore all things in the sea are fish"

One of the crucial ingredients of successful education is the ability to learn from mistakes. Structured clinical reasoning should limit those mistakes to within a margin of safety. Unstructured reasoning, in a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.

"it ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you should know for sure that just ain't so"

(Mark Twain)

"Liberate your mind and only then will you find your freedom"

(Malcom X)

Table of Contents

Mind Maps - clinical examples

Treatment as a product of systematic assessment and reasoning

Introduction

Clinical reasoning is the process by which the Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist assesses the client's dysfunction. Titled Australasian Musculoskeletal Physiotherapists are trained in the superior clinical reasoning skills required for independent self-directed reasoning. The cognitive and meta-cognitive skills required for clinical reasoning may lead to expertise if applied clinically for at least 10 years. This process not only allows the clinician to recognize their limitations, moreover it empowers the clinician to know how to plug any gaps in their knowledge by either researching a particular topic and/or attending post-graduate training courses (self directed learning). These skills are founded under the umbrella of life long learning (the 3 L's).

It is important for the clinician to

- Identify and prioritise professional and personal goals they want to achieve in a set time frame.

- Recognise the key components of effective goal setting.

- Clearly define goals based on their organisational role.

- Motivate themselves and their team to attain their goals.

- Identify key obstacles to achieving individual and team goals.

- Create action steps to accomplish individual and team goals.

- Develop techniques to ensure follow through.

Hereby, the clinician can try to optimise the environment in which they wish to thrive.

However, Taylor (1979, 1986, 1987) described 4 phases of development which include

- detachment

- divergence

- engagement

- convergence

and associated transition points that result in

- disconfirmation - major discrepancy between expectations and experience

- disorientation - confusion and a crisis of confidence

- naming the problem - without blaming self or others

- exploration - open ended exploration with a gathering of insights, confidence and satisfaction

- reflection

- reorientation - a major insight with a simultaneous new approach to learning/teaching/treatment

- sharing the discovery

- equilibrium - new approach is elaborated, refined and applied

Clinical Reasoning is analogous to travelers on a highway. Some are the drivers, others are the passengers. Through experiential learning, the passengers curiosity and confidence can be aroused to become a driver. All the travellers must obey the same road rules, yet they all have a different skill set. The road rules are the consensus of professional practice, whereas the skill set reflects experiential clinical learning. The highway represents the algorithmic structure of assessment, inductive and deductive reasoning. This highway becomes a freeway once these algorithms are rehearsed and automated from frequently repeated subjective and physical examinations. Similar to highways linking towns, the examination links historic events and involvement of body structures, which have either precipitated or have become involved with the current dysfunction. Once the travellers arrive in the town, they experience a more complicated maze of streets with innumerable possibilities. Similarly, as the clinician hones-in on the precise nature of the problem, the experienced clinician uses a more nebulas reasoning process, which may resemble 'fuzzy logic' whereby they recognize clinical patterns based on their unique past experiences or they recognize a novel clinical reasoning experience, which will require inductive as well as deductive reasoning. Similarly, the travellers in the town can use more cumbersome roads to get to their destination or they may know a more optimal route based on examination of the street directory, previous learning, as well as asking local people for advice. In particular, the experienced clinician has the wisdom to acknowledge their own limitations and thereby know when to ask specialists for advice and refer their clients to them. However, there are many clinicians who can become trapped by their own biases, which certainly can help their specific group of clients. Yet, have they had the skills to recognize where treatment hadn't been optimal? Have they contributed to the client ending up on an orbital freeway, unable to get off and explore the town and hence alternative possibilities for reaching their destination through novel management of their condition?

Proofs

- What is proof?

- is a correct argument which establishes the truth of a clinical reasoning statement

- starts with assumptions called hypotheses

- is a sequence of correct musculoskeletal physiotherapeutic steps

- ends in a conclusion

- The purpose of proof

- to convince : proof helps you decide if and why a statement is true or false

- to understand : proof helps you decide how and why all the different assumptions play a part in the result

- to communicate : musculoskeletal physiotherapists use proofs to debate ideas with one another

- to organise : proofs help you organise your thoughts

- to discover new clinical pictures : by carefully examining each step of a proof, musculoskeletal physiotherapists discover new musculoskeletal physiotherapy

- Advice of writing proofs

- state what you are proving 'working hypothesis'.

- include enough detail to make your proof easy to check

- your proof should be written in good English -

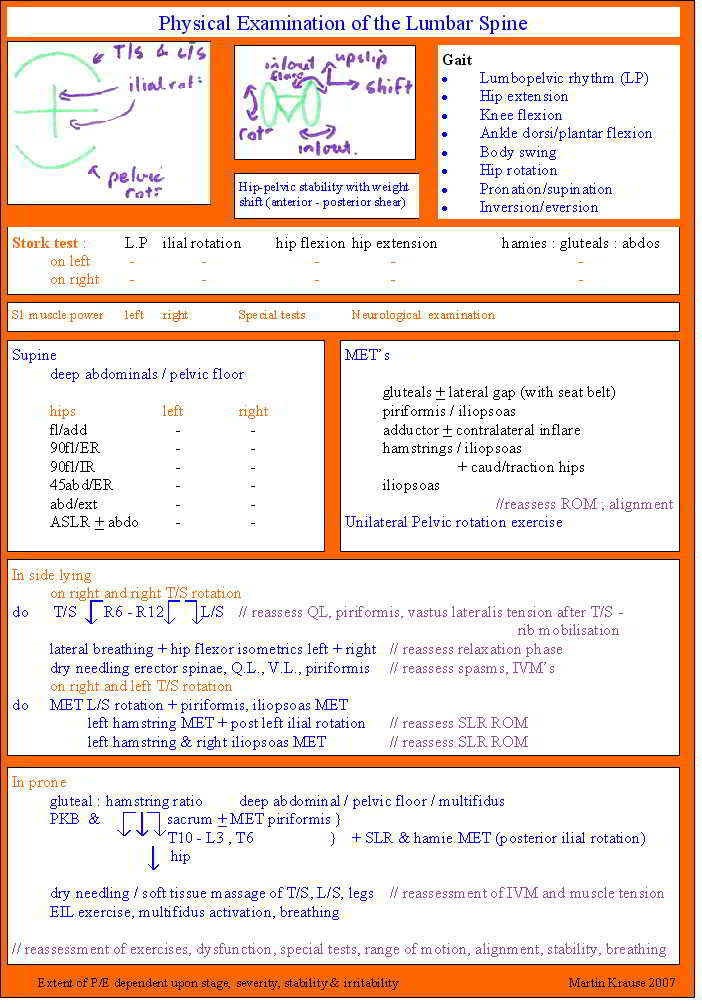

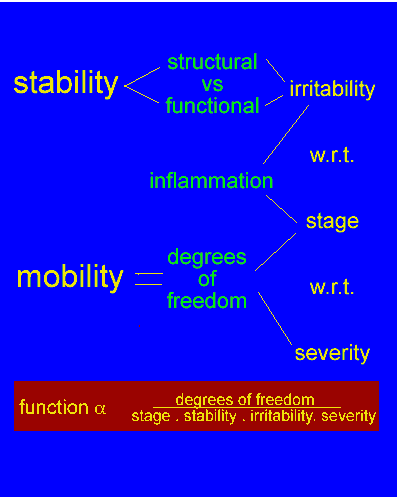

- defining the stage, stability, irritability and severity of the problem (see below or see clinical example)

- determining the cause ; misuse, abuse, overuse, disuse (see below or see clinical example)

- identify the structure and pathology involved

- determine the scope of the problem and thereby depth and breadth of the intervention strategy

- present a predicted timeline of change and how the treatment intervention changes and adapts to each new scenario

- use your layout to clearly separate the parts or different cases considered in your proof

- use diagrams where appropriate to give a visual representation of the situation eg flow diagrams or mind maps.

- it is useful to use examples when exploring a problem as a single example is insufficient to complete a proof. If it is the constructivist reasoning which is being proven, then examples of other pattern recognition and laying down of complex mind maps may be a useful extrapolation and comparison when communicating your argument (eg mind maps, decision making and cognitive constructivism in orienteering)

- check to see where you have used each hypothesis. If you have not used a particular hypothesis then either

- you did not need it

- your proof should have made use of it and therefore is incorrect

- do not expect to write a complete proof the first time. The clinical pattern may emerge on subsequent visits, in response to treatment and exercise intervention

- Local connectives

- and = conjunction

- or = disjunction

- not = negation

- if....then = implication (Boolean logic) - when we deduce one thing from another. Statement A is the hypothesis and statement B is the conclusion

- if and only if = equivalence

- Proof by deduction

- by creating an hypothesis we claim a proof by implication or deduction

- proof by deduction is a direct proof because we start with an hypothesis and work forward to the conclusion

- Proof by equivalence

- two different treatment strategies have the same outcome

- Proof by exhaustion

- a proof can sometimes be split into a finite number of cases, each of which is then proven separately

- it is important to justify why the list covers all possible scenarios

- Proof by contradiction : Reductio Ad Absurdum

- in this form of argument, attempting to disprove a statement inevitably leads to a ridiculous, absurd or impractical conclusion

- to use this we start with a negation (opposite) of the conclusion, and correctly prove that it leads to a contradiction of the hypothesis. We hence deduce that the assumption was false and hence the conclusion must be true

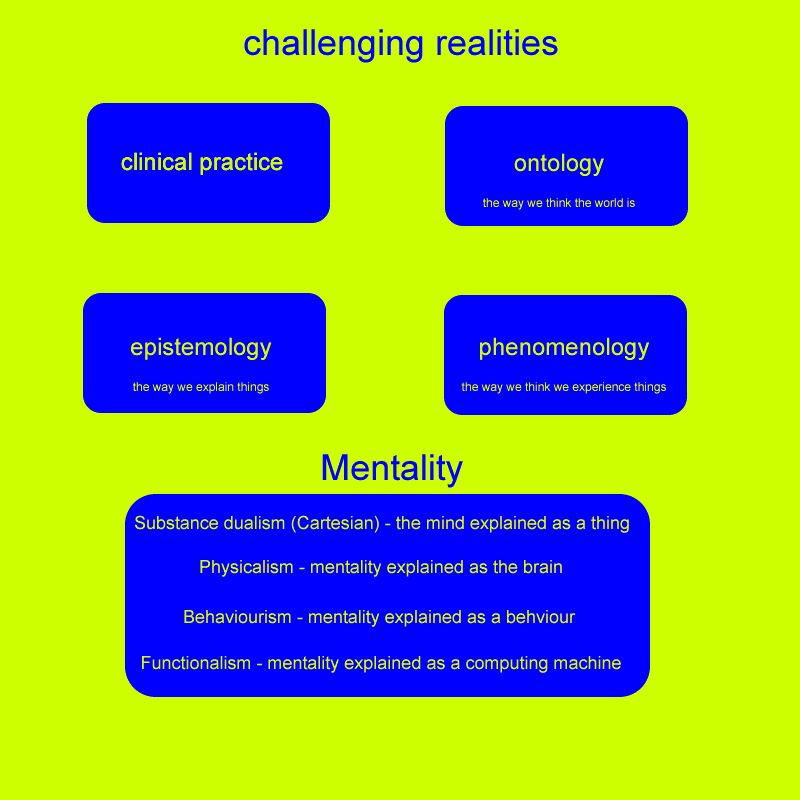

Philosophy and pain

An exciting approach to challenging realities is the examination of the Pain and Philosophy of the Mind (Alex Cahana July 2007, Pain Clinical Updates, Vol XV, 5). Cahana argues that 'mind-body supervenience' (physicalism or materialism) where pain always has a physical substrate, isn't enough to explain the qualitative nature/character of pain ("qualia" = what it is to be).

The problem with physicalism as argued by Cahana is that 'you are nothing but your synapses' ("eliminative") or 'you are ultimately your synapses' ("reductive" or "token").

Cahana (2007) concludes by stating that "pain cannot be separated from the person experiencing it, and the human experience cannot be omitted from a scientific explanation of how our mind works. Therefore, a new subjectivist, interpretive, phenomenological stance is needed in order to capture the complexity of the patient's narrative experience (narrative dyad)".

Thoughts lead to feelings which lead to either action or inaction whereby either activation or deactivation of problem solving takes place. This applies as much to the therapist as to the client who is suffering from pain. Through clinical prediction, environmental prediction can be more finely tuned by the feelings which have preceded the situation that has taken place. The therapist and the client need to embark in cognitive strategies which include ascertaining feelings and beliefs, appraising the adequacy of the response and then if necessary using problem solving to be able to use realistic goal setting (rather than fear -avoidance behaviour) to establish a paced response. Success (by the therapist and the client) leads to better predictive outcomes and thereby should become self-fulfilling.

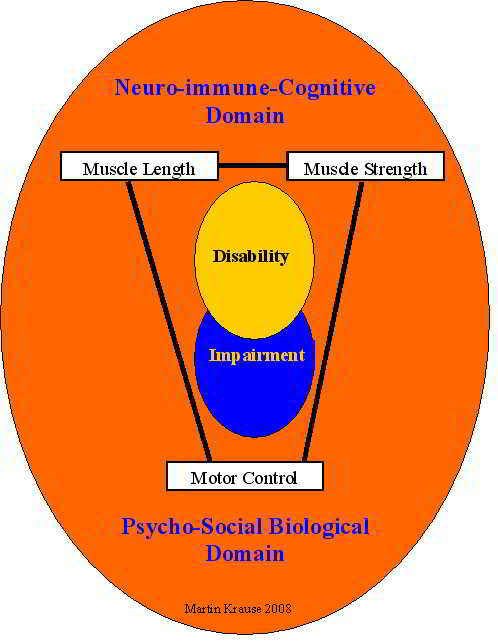

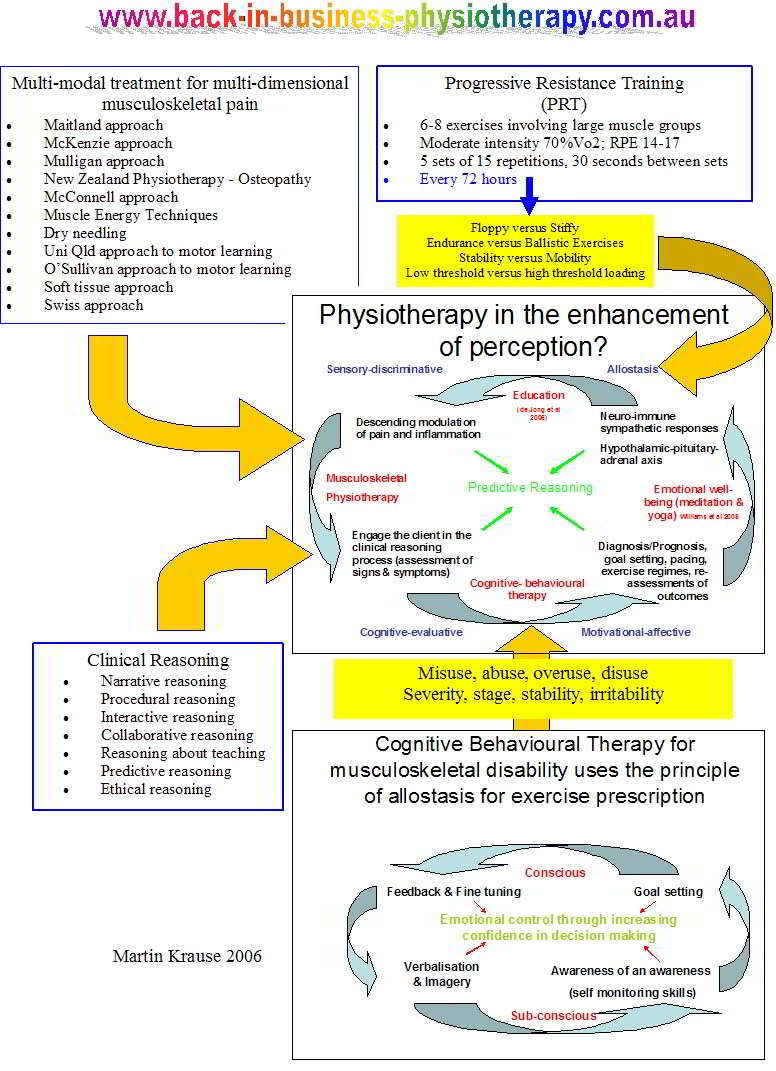

Figure 1: A model of predictive reasoning which has been propagated in physiotherapy since the early 1990's (based on the work of Barrows & Tamblyn 1980)

Scope of Practice

C.B.T = cognitive behavioural therapy ; N.L.P = neuro-linguistic programming

Figure 2 Multiple hypothesis formation and refinement of management strategies

Pattern Recognition and Mind Maps

Ultimately, the clinical reasoning process can be divided into a process of confirmation or negation either through positive diagnostic testing (eg Faber's test, Speed's test etc etc) with their inherent problems of validity and reliability or the process can involve treating a structure and evaluating the outcome by re-examining both the impairment and disability issues which the client presented with. The clients cognitive-linguistic appraisal of outcome can also be evaluated through the re-evaluation of the significant findings from the subjective examination.

Mind maps are a useful guide for the experienced clinician as they not only chunk together information but also provide a sequential structure for processing multiple information. Mind maps can provide a useful schemata for 'brain storming' and lateral thinking. Furthermore, mind maps provide a useful clinical aid to explaining cause and effect to the client, particularly when multiple sites of pain are present. Links to mind maps of some clinical conditions

- tennis elbow

- anterior hip pain

- hamstring injuries

- pelvic neck dysfunction in a cyclist

- Upper Cervical Spine Structural Instability

- Nutritional considerations and cramping in triathlon

- Knee pelvis back dysfunction in a runner with overactive Transverse Abdominus

- arm pain from L5 IVD hernia (with reference to FBL and Susanne Klein Vogelbach)

- pins and needles, numbness in cyclists feet - including biomechanical & vascular compromise

- carpal tunnel syndrome from upper cervical spine dysfunction? - including biomechanical & vascular compromise

- Gastrocnemius tightness - including biomechanics (inverse dynamics, young's modulus, kinetic energy)

As the physiotherapist gains clinical expertise their predictive reasoning or forward thinking should improve. The majority of our cognitive processing occurs in our subconscious whereby routines only change when their is a variation to our expectations. As such, the repeatedly rehearsed, systematic and structured clinical reasoning routine allows for cognitive efficiency. The experienced clinician can 'chunk' clinical patterns into recognizable objects, whereby many variables can be grouped into a meaningful piece of information. Since, the conscious brain can only process one piece of information at any one time, and only hold 6 pieces of information in short term memory, the reduced cognitive demands of 'chunking' allows the experienced clinician to increase the scope of their clinical expertise. Particularly, in more complex multi-dimensional musculoskeletal problems the Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist should be able to apply a multi-dimensional treatment approach. The discerning Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist uses correlations between disability measures with impairment measures such as restrictions in motion, altered form & force closure, inefficient force transmission, as well as cognitive behavioural factors to ascertain whether they are dealing with a familiar or unfamiliar 'clinical pattern'. The validity of each treatment technique is ascertained by their impact on disability and impairment measures. Predictive reasoning and a successful outcome confirms already established 'clinical patterns' or allows for the recognition of a new 'clinical pattern'. This new 'clinical pattern' can then be laid down into the long term memory and be used by the more efficient subconscious reasoning at a later date. Thus, similar to a 'grand master' chess player recalling thousands of strategic moves from famous games, the experienced clinician can recall clinical patterns and the processes needed to confirm these patterns in an efficient manner.

More precise research and formulation of clinical reasoning concepts has come from Mark Jones and his collaborators, in South Australia. Categories of reasoning which an experienced clinicians undertake include

-

Diagnostic reasoning

-

Narrative reasoning

-

Procedural reasoning

-

Interactive reasoning

-

Collaborative reasoning

-

Reasoning about teaching

-

Predictive reasoning

-

Ethical reasoning

Hereby, they have presented arguments for undertaking research paradigms which provide evidence for the superiority of this approach over protocol recipe based approaches. Moreover, the clinical reasoning approach supports/validates the use of techniques which improve disability and impairment measures. Hence, the physiotherapist and client can achieve immediate gratification when improvements are demonstrated. Similarly, if improvements are not forthcoming, then the process allows analysis and re-analysis (cognition and meta-cognition) of strategies already undertaken and rational decisions can be made because of the systematic nature of this approach. Thus, both the client and physiotherapist can actively learn during this process.

La Havana, Cuba, 1995

Learning hypothesis

When considering continuing education some issues of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) may become relevant to physiotherapists.

Neuro = neurological processes affecting thoughts and emotions and subsequent behaviour

Linguistic = communicate with others and influence experience

Programming = internal thoughts and patterns of behaviour that help evaluate situations, solve problems and make decisions.

Achieving excellence requires

-

effective communication

-

motivation of yourself and others

-

thinking positively

-

creating actions to make a difference

OUTCOMES : should be S.M.A.R.T = specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timeframe

-

Creating a well formed outcome means that your goals are stated positively, is clearly context defined, and identifies the resources you need to achieve your goal. Remember each journey commences with a single step

-

Flexibility is about acknowledging that everyone interprets situations through their own perceptions, thereby creating their own reality. Situations change with an ever-changing environment. Flexibility allows you to gather information from a variety of sources, from different perspectives and from different points of view.

-

Rewiring your thinking involves changing your habits, developing new approaches to old situations, replacing limiting thoughts with enabling ones thereby gaining a new perspective.

-

Language filters include deletion, distortion and generalization.

-

Identify who you are, where your beliefs and values lie, what your capabilities are, and in what environment will your behaviour change when challenging your ability to reach your purpose in (professional) life.

-

Map out a structure which reflects both your personal and professional goals starting from some point in the past and going to some specific time in the future to enable you to be yourself. By identifying your time-line, you will be able to pace yourself as you acquire the tools to reach your goals.

-

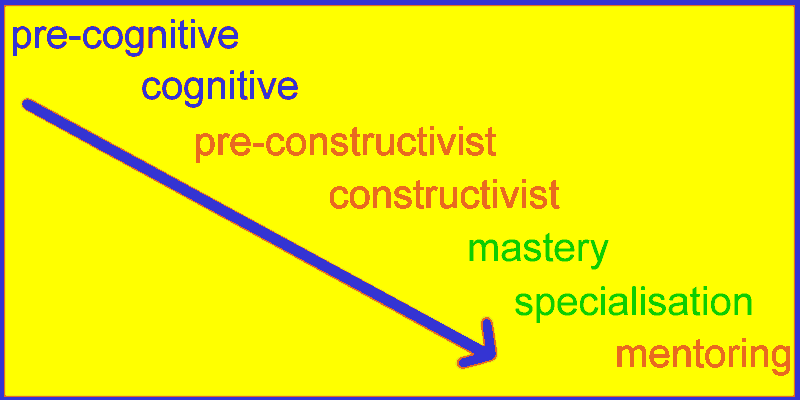

To create mastery through self-directed learning you need to go through 4 stages of learning a new skill

Unconscious incompetence : learning a new skill for the first time, not knowing what you don't know

Conscious incompetence : realizing what you don't know and what you still need to learn

Conscious competence : building the new skill and capability, and feeling familiar with them

Unconscious competence : expertly using the tools like they were second nature (e.g. driving a car)

Hence, the post graduate learning which you undertake should reflect the analysis of yourself.

A word of warning

Consider the Schroedinger's Cat phenomenon where the observer's observations affect the outcome. Clinically, a uni-dimensional approach may always seem to achieve the desired outcome, thereby never really testing yourself, nor encouraging you to improve your clinical competency base. If there is little which you are looking for then there is little which you will see, and that which you see will be what you want to see. Incredibly, some of the people who frequently write the text books aren't clinicians. The most extreme case I know is a physiotherapist with only 4 years clinical experience who is writing a book 'about everything to do with musculoskeletal physiotherapy'. So, try to gain your practical clinical experience from as many sources as you possibly can, as people with a guru status often come with a bias. The best people to teach clinical expertise are clinicians. Particularly, if you are going to undertake post-graduate physiotherapy training make sure that the facilitators are current and have at least 10 years post graduate clinical experience. Peter O'Sullivan at Curtin University and Gwen Jull from Queensland University are two brilliant clinicians which spring immediately to mind. Other people who I've had the good fortune to meet and who have embark on a process of clinical excellence are Alfio Albasini of Ticino (Switzerland), Wim Dankaerts from Belgium, Abrahao Batista from Salvador do Bahia (Brasil) and Luis Henriquez from Santiago de Chile.

The clinician/researcher who is able to construct the question, have firstly realize a problem which requires the framing of a solution through the formulation of possibilities, probabilities, improbabilities and unknowns. Hereby, they are on the road to finding an answer, which along the way may throw up some new and intriguing questions as well as solutions.

Cognitive structure

Importantly, the ultimate cognitive goal for deductive and inductive clinical reasoning is to attain and store knowledge in a coherent and meaningful structure, ready for quick retrieval. In the face of clinical pattern recognition, the working hypothesis can be tested and re-tested and altered as clinical findings come to light.

If there are only

- 5 primary colours (red, green, blue, black & white),

- 5 basic notes (A, G, B, D, F)

- 5 basic tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, savoury, salty)

- 5 types of intelligence found in literature (scientific, philosophy, serious fiction, history, poetry)

which can give rise to an infinite number of combinations, then what are the quintessential elements of physiotherapy?

Multimodal Treatment approach to enhance the scope of practice

Figure 3: A model of 'everything' ?: the neuromatrix is used as a model (cognitive process oriented structure) to describe the various input which the therapist can offer to 'enable' the client to engage in their path to recovery. Hereby, an evidence based approach using 'the values and beliefs' of the client is integrated with the scientific evidence base from physiotherapy, the pain sciences and psychology. Importantly, the therapist gains confidence through their success at predictive reasoning, whilst the client gains emotional confidence in their ability to undertake goal-oriented activities without the fear of exacerbation or under-performance. A definition of expertise should encompass the ability to perform accurate predictive reasoning.

|

Multiple Intelligence

"Gardner defines intelligence as the capacity to solve problems or to fashion products that are valued in one or more cultural settings. MI initially consisted of seven dimensions of intelligence (Visual / Spatial Intelligence, Musical Intelligence, Verbal/Linguistic Intelligence, Logical/Mathematical Intelligence, Interpersonal Intelligence, Intrapersonal Intelligence, and Bodily / Kinesthetic Intelligence). Since the publication of Frames of Mind, Gardner has additionally identified an 8th dimension of intelligence: Naturalist Intelligence, and is still considering a possible ninth: Existentialist Intelligence "- see Wikipedia

- http://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/philosophy_in_physiotherapy

Sequence of learning through applied clinical reasoning

Human's are prone to taking short-cuts known as "heuristics". Although they generally serve us well, they often cause clinicians to make predictable errors. Generally, biases favor hawkish advice. These include

-

the optimism bias. People are prone to exaggerating their strengths. People generally believe themselves to be smarter, more attractive and more talented than average. They commonly overestimate their future success. This can lead to "illusion of control" whereby they consistently exaggerate the amount of control they have over outcomes, even when those outcomes are determined by luck or other variables.

-

the fundamental attribution error. Even when people are aware of the possible constraints on another persons behaviour and know a lot about the context in which the client is acting, they often don't take it into account when assessing the client's motives.

-

risk aversion bias. An assumption is frequently made that people are "risk averse" but it turns out that we are predominantly "loss averse". The clinician may be prepared to run a risk in the slim hope of avoiding having to recognise a loss.

Due to the ease of being drawn into 'pattern recognition' and hence potential biasing, it is important for the clinician to maintain a structured cognitive retrieval process whereby recognition of desired and undesired outcomes leads to conformation or negation of the clinical reasoning hypothesis. Hopefully, when negation does occur, it occurs early in the reasoning process; otherwise the treatment management plan can spiral 'out of control' leading to the therapist taking greater and greater risks in the hope for a miracle. Hence, the clinician will need to be able to think back to first principles of anatomy, physiology, neurophysiology, pathology and biomechanics to be able to undertake the process of reasoning required to achieve the desired outcome. This formulation of outcome should in turn be a consequence of the dialogue within the therapist's brain (cognition & meta-cognition) as well as the dialogue between the client and the therapist.

Constructivism describes the process of learning and acquiring knowledge through experiential reasoning. The assumption underlying 'constructivism' is that we are 'life long learners' (3 l's) and that each and every clinical encounter allows a unique opportunity to learn, relearn and refine our techniques as well as reorganise and restructure our knowledge base. Furthermore, constructivist theory suggests that learning occurs which is based on each individuals unique prior experiences. Truth is considered relative to the individuals construct and hence diverges from logical positivism of science where 'truth' can exist alone without reference to the observers perceptions. This is similar to scientific philosophy of 'relative truths' or the 'relativity of knowledge' espoused by Feyerabend (1975), Kuhn (1970), Popper (1963). All of us would agree that science isn't just a collection of laws, or a catalogue of unrelated facts. Rather, it is a creation of the human mind relating to making sense of the world. Hence, in musculoskeletal physiotherapy we must endeavour to match the science with our clinical reasoning which should make sense to the individual or organisations with whom we are interacting.

Candy (1991, p 263) states that "the constructivist perspective differs significantly from the view of knowledge as deriving from a process of copying or replicating." Hence, "we know reality only by acting on it.....The active interaction between the individual and the environment is mediated by the cognitive structures of the individual......and what we learn from the environment is dependent upon our own structuring of those experiences." (Nystedt and Magnusson 1982, p34)

To the constructivist, knowledge is not a precise map of external reality but a schemata or cognitive structure which can be compared or tested to other peoples construction of the same situation through the use of workable hypothesis or templates (Candy 1991, p 265). Domain specific prior knowledge plays a significant role in the process of construction, problem solving and learning. Systematic procedures for problem solving can be learnt which if content and context specific can lead to advanced clinical reasoning where errors in heuristic procedures can be detected immediately through the continuous testing of the working hypothesis and it's evaluation of the relevance of clinical data to the specific problem at hand. Hereby, not only can reliance on 'heuristics' be monitored but new schemata can be construed from the clinical environment when a clinical presentation occurs with which the clinician is unfamiliar.

Heuristics versus Constructivism

Figure 4: A useful instructional model used to describe a 'top-down' clinical approach with a scientific clinical evidence based approach of biomechanics and neurophysiology. Importantly, the cognitive and meta-cognitive aspects of clinical reasoning are only as good as the diagnostic tools available to the therapist. Hence, excellent manual handling skills and refined but diverse treatment techniques (e.g. trigger point dry needling, soft tissue massage, fascial release, muscle energy, exercise prescription, taping, PAIVM's and PPIVM's) allow for a correlated and integrated approach to treatment. Refinement of reasoning techniques requires frequent repetition of experiential learning.

Clinical Reasoning can be a conduit for the deconstruction and reconstruction of information storage and retrieval systems. This systematic approach allows for the redefining of the situational relevance of perceived information into a 'meaningful clinical picture' whereby correlation of information can be used to confirm or negate a 'reasoning (working) hypothesis'. "Mindfulness" and "Mindsight" has been used by Dan Siegler (2010) to describe the correlation of subjective internal realities with external physical realities. Similarly, Geoff Maitland developed a process of clinical reasoning, in the 1970's, whereby the 'meaning' of information is ascertained through the intra-correlation of the subjective experience with the intra-correlated physical presence or being.

Figure 5: Increasing the validity and reliability of the clinical reasoning process by correlating all aspects of the subjective and physical examination into a meaningful clinical picture (pattern recognition) - adapted from Maitland (1986, 1991). Click on above image for further explanations regarding the development of the Maitland concept.

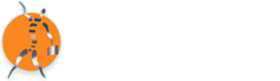

An example of the sequence of physical examination for a problem in the back-pelvis-hip region. To provide validity of this management approach, the results of the physical examination and treatment must be correlated with the findings in the subjective examination. Hence, meaning and relevance of the physical examination and treatment can only be obtained through the clients 'subjective quantifiable' experience. In this manner an integrated coherent narrative can be attained by both the therapist and the client, thus allowing a harmonious client-therapist relationship to ensue.

Disability

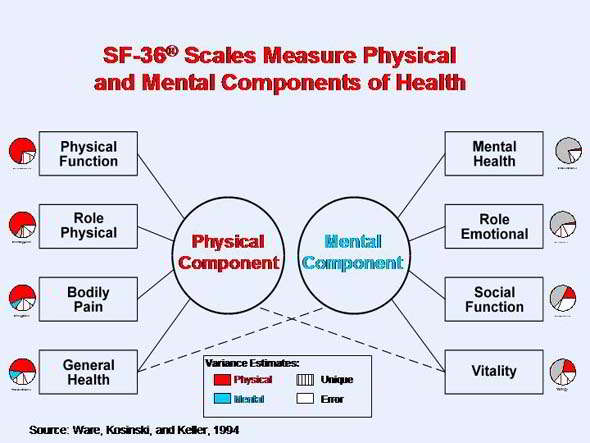

It is important to appreciate that there isn't a linear relationship between impairment and disability. Disability contains quality of life perspectives which has psychological and social constructs as well as the more visible physically measurable impairments. Health Quality of Life (HQoL) gives the physiotherapist with another avenue to pursue evidence-based practice (EBP) which include the third pillar of EBP, patient values. (see O'Connor R 2000 Measuring Quality of Life in Health. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston. ISBN: 0443073198)

Psychometric evaluation

When traumatic events involving anxiety and/or pain occur, they can be stored in memory using a process which does not distinguish a timeline of activation or extinguishment of the experience. Hereby, previous traumatic experiences can be conceived as a present traumatic experiences causing further fear and anxiety. Ramachandran has suggested that it can be the preoccupation with the trauma that is disabling. Hence, the concept of allostasis has been included in the neuromatrix described previously in figure 3. Psychometric evaluation is now considered mandatory in NSW when treating work accident related cases.

http://www.sf-36.org/tools/SF36.shtml

The Oerebro scale is another useful psychometric questionnaire which is recommended by Work Cover NSW

Other areas of assessment may include

- visual fields and visual dominance

- spatio-temporal abilities such as juggling

- sport specific physical and psychological aspects

This latter aspect of assessment may include a 'top 10' attributes list compiled by the client/athlete of both physical and mental performance in an ideal world. Then the therapist can ask the athlete to rate their present sport specific perceived abilities. Additionally, their coach may also be presented the same list and ask them to rate the athletes abilities. This is obviously undertaken without the coach seeing what the athlete thought of themselves. Hence discrepancies can be assessed, measured and addressed. Psychological aspects can be addressed by a Sports Psychologist whereas the physical aspects can be addressed in tandem with the Psychologist, Physiotherapist and Trainer.

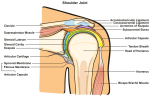

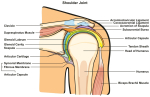

Treatment as a product of a systematic assessment

Although an at 'out of fashion' terminology, the aggravating/easing factors are a disability measure which can be used to assess the neurophysiological and biomechanical state of the pathology. By analysing the movement and loading characteristics of the aggravating and easing factors the therapist should gain a measurable outcome tool for assessing the efficacy of treatment. Additionally, the information can be used to correlate it with impairment measures of the physical examination. Improving the internal reliability by correlating information across the entire examination process enhances the validity of your treatment and re-examination process. Ideally, the therapist should have at least 3 aggravating/easing factors to assess outcome. Otherwise, a more in depth analysis of the aggravating/easing factors should be undertaken using inductive reasoning. For example, if the client only complains of shoulder pain when lifting a load above their head, then clarify this statement by asking whether it is the movement which is painful, the duration of lifting, the manner of lifting or the size of the load which is being lifted that is significant. Night pain, the frequency of waking and the ability to return to sleep are also useful measurement tools. Psychometric disability measures can also be used if they don't result in resentment or irritation from your client.

Further aspects of the subjective examination can be used to assess the past history as it relates to the current problem. Is it the same problem re-aggravated or is it a new problem which is influenced by the old injury? Assess the biomechanical aspects of the original mechanisms of injury as well as those of re-exacerbation, as well as the frequency of exacerbation and make a judgement as to whether the problem is getting worse, better or staying the same. If it is getting worse, then why? Are there components of misuse (reduced co-ordination/stability), disuse (atrophy and reduced capacity of loading), abuse (trauma), or overuse (repetitive loading and microtrauma) which are contributing to the 'cause of the cause' of the problem. A long history of problems may identify fear-avoidance behaviour and generalised 'disuse' and/or of more specific 'disuse' of the multifidus and transverse abdominis muscles. Combine this with 'overuse' of the erector spinae muscles leading to excessive compression of the intervertebral disc and consequent neural irritation of the dorsal root ganglia resulting in ectopic impulse generation and increased muscle tone in the deep hip rotators, hip flexors, hamstring and calf muscles which creates 'misuse' of the lower limbs ('the tail that wags the dog phenomena') generating shearing and rotating forces across the pelvis.

There are TWO areas of the clients history that are able to give you an accurate prediction of injury

1. Past Injuries – regardless of how long ago the injury happened

2. Current exercise training volume – obviously the higher the training volume the higher the risk of developing overuse and biomechanical injuries.

A good history should include:

a) Past Injuries – especially those that resulted in surgery, joint disturbances and scar tissue

b) General Health – a rundown client does not recover as well and is more prone to overuse injuries

c) Colds and Flu – limited recovery is available when the client is recovering from general and common medical disorders

d) Sporting Background – some athletic populations have common injury areas e.g. tennis players elbows, swimmers shoulders, gymnasts have excessive flexibility and stability issues in their backs and shoulders, and wicketkeepers knees.

e) Exercise History – clients often mention that they exercised in the past but had to stop due to injury – this information is vital as combined with a physical assessment you can identify the causative factors and re-structure their exercise program to avoid the same mistakes again.

f) Current Exercise Problems – is there any current exercise or activity that causes pain during or after the session.

g) Employment History – certain lines of work also have increased risks of injury for certain body parts. Office workers can have muscle range limitations, truck drivers can have back issues due to excessive vibration and carpet layers commonly have knee and back issues.

Old injuries may not only reduce the biomechanical integrity of the tissue but it may also increase the neurophysiological sensitivity of the neurones whose nerve fibres innervate the territory of injury. Ascertaining the recuperation from previous injury will provide an insight into the clients 'active' and/or 'passive' coping strategies. People who have had frequent passive treatment inputs and have recovered may find it difficult to embrace a more active treatment approach. Those who haven't recovered may be in a state of 'learned helplessness' who will similarly require convincing to embark on a more active form of recuperation. Importantly, the active treatment approach must embrace the impairment and disability measures of the subjective and physical examinations, thereby allowing the client to measure success leading to the ultimate goal of full self management and/or complete recovery. Therefore, this process requires an element of education whereby the therapist's 'hands-on' treatment becomes 'exercise enabling' and/or 'performance enhancing' for the client.

Figure 6 : The application of treatment will vary with the stage, stability, severity and irritability of the condition. The stage describes whether the condition is getting better, worse or staying the same. The stability is considered both mechanically, behaviourally and neurophysiologically. The severity is the impact the injury has on the person's activities of daily living. The irritability defines how easily the symptoms worsen and relates to how quickly they get better. These factors will influence the goals of the client which should direct the aims and objectives of the therapist. In line with Maslow's formulation of individuals 'needs' the process of clinical reasoning and perfection of treatment skills should lead to expertise in the clinical domain and subsequently to a state of "self actualisation" As the physiotherapist's success and treatment scope improve, self actualisation can be attained through their reflective skills, which enables the therapist to recognise 'gaps' in their integrated knowledge base. Such realisation should result in actively seeking the knowledge and/or competency skills required to reduce the size and number of 'gaps'. However, this expertise can only be gained through the 3L's.

Maslow (1971, p43) defined the attributes of "self actualizers" to include

- the acceptance of self and others

- spontaneity and naturalness

- autonomy and independence

- freshness of perception

- genuineness in relationships with others

- creativity

- positive self concept

- involvement in a cause outside of themselves

Figure 7 : Defining the aspects of the examination heightens the therapists cognitive abilities and hence clinical agility. Reflective skills as treatment is instigated and outcomes are measured enhances the therapist's meta-cognitive skills (thinking about their thinking)

Figure 8 : Examining the 'cause of the cause' will get to the root of the problem. By deconstructing the problem, clear and precise explanations can be given whereby the aims and objects of treatment commensurate with the goals of exercise

The stage, stability, irritability, and severity will determine treatment options as well as the dose of treatment - here an example for a lumbar radiculopathy is given

Cause & Affect

Treatment is usually directed at the primary problem for which the client has presented. As the primary problem resolves the cause and affect of the injury must be taken into consideration if an holistic approach is to be considered. Low back pain would address issues of thoracic spine stiffness in rotation, lateral bending and inferior lateral chest expansion as these areas influence the lateral movement of the diaphragm during breathing. In turn this affects the use of the oblique stomach muscles, the transverse abdominus and psoas major. Furthermore, the ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system attach to the anterior aspect of the posterior ribs and their function is influenced by rib movement, which can potentially affect the control of muscle spasms and blood flow to the spine and lower limbs. Finally, deep slow lateral breathing reduces the risk of respiratory alkalosis and hence metabolic acidosis which can affect soft tissue integrity. Looking below the lumbar spine, addressing the pelvis and hips using joint mobilizations, soft tissue massage and muscle energy techniques would affect lumbo-pelvic rhythm. Muscle spasms can be addressed by reducing inflammation and/or relieving mechanical pressure on nerve fibres thereby decreasing ectopic impulse generation. Additionally, dry needling and soft tissue massage of the muscle fibres may also be employed. Exercise regimes to complement the specific impairment outcome measures should be integrated into functional exercises which resemble activities of daily living. Naturally, the clients motivational & emotional state needs to be monitored if a collaborative approach to recovery is to be obtained.

Treatment Failure

In most cases musculoskeletal disorders resolve within 6 weeks. Where greater structural damage has occurred, the resolution of impairment and improvement in disability can take 6-12 months. However, in some cases, dysfunction becomes prolonged causing suffering and reduced vitality.

Reasons for failure of resolution are numerous. However, generally they can be classified as simple or complex. Simple problems are localized dysfunction which wasn't managed correctly in the acute phase resulting in disuse impairment and de-conditioning. Such de-conditioning can take on multiple dimensions. Where a simple ankle sprain leads to atrophy of the leg muscles, reduced cardiovascular fitness, increased weight, neurological-immune-cognitive impairment and even metabolic syndrome. Complex problems arise where multiple structures in various locations have been injured in scenarios of major trauma such as car accidents, skydiving, gun shot wounds, etc. Again, the secondary issues of trauma involving whole body function are the consequence of prolonged recovery. In both cases active involvement by the client in the rehabilitation process are paramount. Moreover, the role of the physiotherapist is to reduce impairment and introduce exercise appropriate for the time line of recovery.

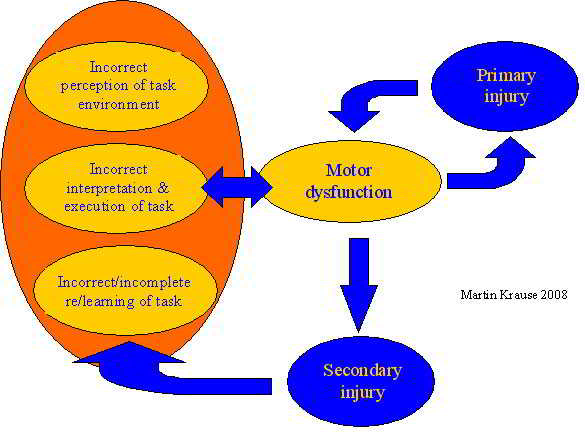

Sporting expertise is gained through repetition of movement and avoidance of (and appropriate recovery from) injury. Frequently, being painfree was considerd to be synonymous with recovery. However, researchers at Queensland University clearly demonstrated that recurrences in injury can be the result of continued abnormal motor function.

In some cases neuro-cognitive issues, arising from 'fear-avoidance' behaviour, occur. This is frequently due to altered sensory information processing. In such cases the client is given the appropriate amount of information to load the body to make it stronger. It is paramount to understand that the intensity and duration of pain is usually not commiserate with 'tissue damage'. In fact 'the pain' now has become the pathology.

The Immune System

The immune system, muscle mass and exercise tolerance can have a profound influence on the clients adaptability to stress, exercise and inflammation. The therapist will need to consider the general health of the client, and in particular their lean muscle mass, when assessing and treating the clients problem. The clients lean muscle mass not only determines biomechanical power, the ability to use insulin, resorb lactic acid to pyruvate by the liver and function as the metabolic end product of the electron transfer chain (ETC) in the mitochondria for endurance outputs, it also directly influences the ability to mobilise immune proteins for an inflammatory defense reaction.

The immune system respond in specific ways to exercise prescription. - link to Rome Presentation

The specificity of goal oriented exercise prescription, can be used for positive immune adaptive responses. - link to nutritional supplementation

Goal oriented exercise prescription and health management regimes can be used to aid the client with their predictive reasoning and hence their adaptive allostatic physiological and behavioural responses. - link to neuro-immune response

Cuba, 1995 - the ultimate in game theory?

Deterministic chaos theory, the outlier and damping oscillations theory

Chaos theory and the Butterfly effect from conflicting descending modulating and peripheral input into the neurones of the spinal cord with inappropriate assessment and treatment

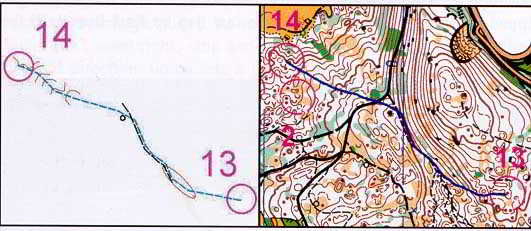

Forward thinking (predictive reasoning) as it pertains to the gaining of expertise in orienteering, motor learning, avoidance of injury and pain management - click on picture below for link

Conclusions

Sometimes it is hard to know what you don't know. It's important not to be constrained by dogma. In each case recognize what you know and compare this with what you don't know. Hereby, a risk analysis can be undertaken to establish the wisdom of your treatment. "A wise person knows their limitations". As each day brings a new dawn, plugging the gaps in your knowledge through life long learning (the 3 L's) can be a most satisfying experience. If you study hard and gain clinical insights from as many respected fields of clinical science as you possible can, you will be able to enhance the scope of your practice and thereby prevent burn-out by recognizing and enjoying the greater challenges of holistic musculoskeletal care. This will not only be to the satisfaction of your clients but also to the greater good of your community. However, the path is a long one, where clinical expertise requires at least 10 years of dedicated learning. I've been a physiotherapist for over 20 years and yet every day brings with it a potentially new learning experience.

Explanations and References

Terapia Manual y dolor (Castellano)

Dolor y Inflammacion (Castellano) PDF

Manual Therapie in der Behandlung von Schmerzen (Deutsch)

Tratamento do dor e inflamacao com fisioterapia manipulativa (Portuguese)

The importance of motor learning in the development of the concept of stability (English)

Exercises in map reading for enhanced cognition (forward thinking - predictive reasoning) (English)

Manual therapy in the treatment of pain and inflammation (English)

Nutritional Supplementation in endurance sport

Exercise and the Immune System (English)

Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes (English)

Exercise and Sarcopenia (English)

Fibromyalgia (English)

Examples of the assessment process for clinical reasoning

Beispiel von Klinisches Denken (Deutsch)

Clinical Reasoning Exercise for low back and lower Limb

Clinical example of treatment for functional instability and radicular LBP

A floppy feeling stiff - accompanied by visceral dysfunction - CREST syndrome

Cyclist riding fixed gear with an overactive right iliopsoas and left knee dysfunction

Multifidus dysfunction - a role for examination of the immune response?

Australian approach to physiotherapy

Publications:

-

Neurophysiological Effects of Traction, Rigaku Ryohogaku (2000), 27,4, 128 (Japan)

-

Lumbar Spine Traction: Evaluation of effects and recommended application for treatment (2000), Manual Therapy, 5, 2, 72-81

-

Neurophysiological effects of Manual Therapy (1996), Kinesiologia, (Chile)

-

Neurophysiological considerations of SLR and ULTT (1998), Kinesiologia (Chile)

- Whole Body Vibration Therapy and Training

We comply with the HONcode standard for health trust worthy information: verify here.

Originally written in 1998

for a Computer Aided Instruction (CAI) development using Macromedia and Dreamweaver for presentations in Zimbabwe, Japan, Chile and Brazil in 1998-2000

Last update : 24 February 2022