An Australian Manipulative Physiotherapeutic approach to the assessment and treatment of Musculoskeletal Disorders.

by Martin Krause

The widespread use of manual therapy techniques suggests some degree of success in their application. The Australian manipulative physiotherapeutic approach to musculoskeletal disorders has evolved over 4 decades to become a part of the health care provider network in Australia. Further, Australian physiotherapy has benefited from the close cultural and geographic ties with New Zealand and their unique approach to the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

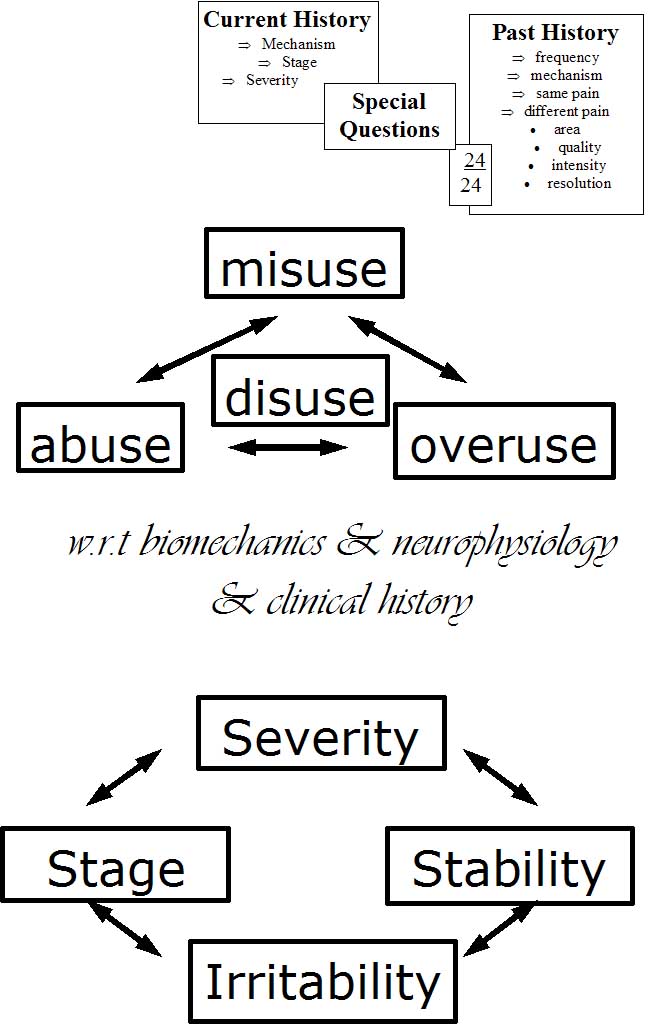

The fundamental concept of treatment of musculoskeletal disorders has been influenced by Geoff Maitlands' manual therapy approach. The concept which Geoff Maitland has introduced is based on clinical observations. These clinical observations have evolved as a result of a systematic approach to the examination and treatment of the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms. This systematic approach involves the evaluation of the patient’s clinical signs and symptoms and the evaluation of the effects of treatment techniques on these signs and symptoms. Since the value of the treatment technique on the presenting signs and symptoms may be assessed, the physiotherapist is left with the ability to find the most effective treatment technique. Through the interpretation (clinical reasoning) of the presenting signs and symptoms concepts such as neural mobilisations and McConnell taping technique have evolved.

Both the patient and physiotherapist need to interact in a mutually constructive way. The information which the patient provides may be interpreted and placed into a meaningful context by the physiotherapist. Further, the physiotherapist may need to ask the appropriate questions in order to confirm and correlate the information which is given by the patient. A physiotherapist may label a patient unreliable when a positive treatment outcome doesn't occur, yet unreliability may occur when either the patient and/or physiotherapist become inconsistent with their response to questions and answers. Maitland states "the patient has one witness whereas the physiotherapist has none" (Maitland 1988). This means that the physiotherapist needs to believe the patient and try to "make the features fit" (Maitland 1986) through an unbiased clinical reasoning approach. Only when "the features" don't fit may the physiotherapist consider the patient unreliable. However, the physiotherapist needs to consider and investigate all possibilities before a patient is 'labeled' (or in some cases condemned) as unreliable. The presentation and the solving of unfamiliar clinical presentations through the correlation of information may assist the physiotherapist to learn and better understand the human being. The ability to adjust our clinical reasoning processes and explore every treatment possibility at the clinical interface makes our profession a very exciting profession to be in.

Since the expectations of a positive treatment outcome on signs and symptoms underlie the success of this approach to treatment, the continued existence of physiotherapy as a primary health care provider in the face of ever increasing economic constraints may attest to the practicalities for the physiotherapist and the satisfaction by patients of this treatment approach. Indeed, the Maitland concept fails to work if a thorough assessment and re-assessment during the subjective and physical (objective) examination are not carried out. Therefore, the Maitland approach makes use of the correlation of information within and between various aspects of the subjective and physical (objective) examination ("Make the features fit" [Maitland 1986]) to increase the validity and reliability of this approach to the assessment and treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. Clinical investigations on manual therapy at the University of Queensland are increasing our clinical knowledge (Jull, Bogduk, Marsland 1988; Jull & Bullock 1987; Jull, Treleaven, Versace 1994) whereas investigations designed to assess the validity of our measurement tools in terms of joint biomechanics (Lee & Svensson 1990), EMG (Lee, Esler, Mildren, Herbert 1993; Shirley & Lee 1993), proprioception and statistical methods (Maher & Latimer 1992) were carried out at the University of Sydney. The ever increasing number of continents where this sytematic approach was being taught and applied in the clinical practice (Europe, Asia, Africa, North & South America) may be attributed to the validity and reliability of the manipulative physiotherapeutic approach to the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

A catchcry for the healthcare dollar (peso) of the previous decades was to "either prove it or loose it" (Jull 1987). The clinical reasoning approach to clinical signs and symptoms is being enhanced by the work of Mark Jones (South Australia) and Joy Higgs (University of Sydney) and by scientific evidence from anatomy, biomechanics and neurophysiology. Knowledge in applied clinical anatomy was stimulated by the works of Nikolai Bogduk at the University of Newcastle, Twomey and Taylor in Western Australia (Bogduk & Twomey 1991). The biomechanical approach in the assessment of neural mobility has been enhanced by Bob Elvey in Western Australia, whereas the neurophysiological approach to manual therapy has been stimulated by David Butler, Michael Shacklock, and Helen Slater in South Australia during the early 1990's. Certainly, the revolution in knowledge in the pain sciences may be reflected in the ever increasing membership numbers of the IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain) of which Australian scientists and practioners such as Michael Cousins (former president) from the University of Sydney have played an integral part. Indeed, it is this fundamental multidisciplinary approach to the validation of the treatment of pain which is integrated into both the IASP and manipulative physiotherapy concepts. However, although theoretical knowledge are important it should not bias the practioners judgement as to the significance of the presenting signs and symptoms. Maitland (1988) emphasises that although new theoretical hypotheses come and go, the clinical signs and symptoms have remained the same for thousands of years.

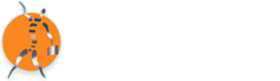

The subjective examination consists of

1. Body Chart

2. 24 hour behaviour

3. Aggravating/easing factors

4. Past History

5. Current History

6. Special Questions

The physical (objective ) examination supplements the subjective examination and consists of the examination of

1. Active movements

2. Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movements (PPIVM)

3. Passive Physiological Intervertebral Movements (PAIVM)

4. Neurological examination

5. Special tests (e.g. neural mobility, impingement, instability tests, vertebral artery, etc)

The treatment should be the final stage in the validating and correlating approach to the assessment of the musculoskeletal disorder (Maitland 1986). Thus, the reliability of the manipulative physiotherapeutic approach may be enhanced by correlating all the information. The reliability of the physiotherapist’s thinking (cognition) is self assessed (meta cognition) through the correlation of all aspects of the physical (objective) and subjective examination and the validity of the treatment technique is assessed through the correlation of all aspects of the physical (objective) examination with treatment outcome (and thus the subjective examination).

During the subjective examination, the distribution of symptoms on the body chart should give the physiotherapist an initial impression (working hypothesis) as to which structures may be involved in the presentation of pain (Bogduk & Marsland 1988). Further questioning as to the type of pain, whether the pain is deep or superficial, whether the pain is constant or intermittent, whether pins and needles/numbness are present should further lead to hypotheses generation in regard to the involvement of somatic and/or nerve root structures. Also the relationship between the pains and pins & needles/numbness may lead to hypotheses generation as to the number of structures involved (Maitland 1991).

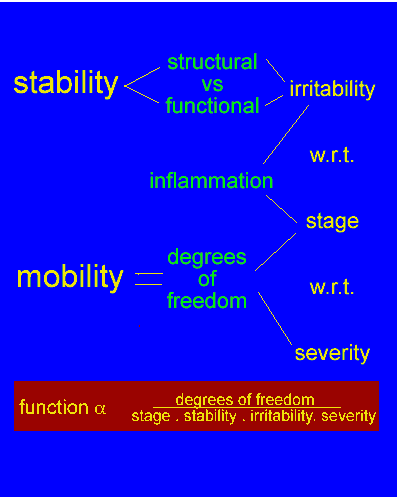

The hypotheses generated by the body chart should be confirmed or denied through the correlation with the remaining examination. The 'aggravating/easing' factors (Maitland 1991) may generate hypotheses as to the movements involved in the patients problem and should correlate to the relationship between the pains on the body chart and later should correlate to limitations in the active movement examination. The aggravating/easing factors should also establish the 'irritability' (time for pain to come on, the intensity of activity required to produce pain, the time taken for symptoms to decrease) of the disorder (Maitland 1991). 'Irritability' is considered to protect both the patient and the physiotherapist during the physical (objective) examination by identifying the proportion of inflammation and mechanical irritation (pain and stiffness) involved in the movement dysfunction. Further, these aggravating/easing factors may provide a valuable tool for reassessment purposes (i.e. time for pain to come on, the time for pain to ease, the severity of symptoms, the distribution of symptoms, the intensity of the activity required to produce symptoms, etc).

The 24 hour behaviour may provide information as to the presence of inflammation and mechanical irritation. Inflammatory conditions tend to be worse at night and are thought to be accompanied by morning stiffness lasting longer than half an hour. Also, heat is thought to give some relief of pain during inflammatory conditions. Further, medication use in the 'special questions' (e.g. the effect of NSAID's) may correlate to the presence or abscence of non-neurogenic inflammation. The 24 hour behaviour may further confirm the relationship between pains and may be a useful reassessment tool (e.g. pain A comes on at 1400 rather than at 1000 and is no longer accompanied by pain B, C, D, and E, etc).

The current history may identify the stage of the disorder, the extent of injury and the onset of pain and correlate the relationship between the pains to that which was established on the body chart, aggravating/easing factors and 24 hour behaviour. The current history may also provide information with regard to a mechanism of injury (specific movement, degree of force involved, etc) which may be related to the aggravating/easing factors and may later be related to the active movement examination. The current history may also help identify the 'stage of the disorder' (i.e. "getting better, worse, or the same?").

The past history may further correlate the relationships between the pains which are being established, the 'stability' of the disorder, and together with the remaining subjective examination an initial hypothesis as to the prognosis of treatment outcome may be made. The 'stability' of the disorder refers to the frequency of symptoms, the intensity of activity to cause a relapse of symptoms, previous treatment, etc. Expectations of treatment outcome may be hypothesised if previous treatment helped, did not help (due to inappropriate treatment or due to the extent of pathology?), if the problem has been getting worse over the past 20 years verses the first occurance, etc.. Treatment progress not in correlation with the therapists expectations may be a good indicator that a particular technique needs to be changed or that another problem exists. Further, the patient may have more confidence in the physiotherapist if treatment goals are defined.

Finally, the 'special questions' should identify the results of medical investigations and treatment (e.g. NSAID's, steroids, operations, etc.) any precautions and contraindications to treatment with manual therapy. Also referral back to the medical practitioner may be necessary at this stage due to suspected cancer, cord compression, cauda equina dysfunction, instabilities, fractures, osteoporosis, systemic inflammation, virus, etc.. In this manner a close working cooperation with the medical practitioner helps in the differential diagnosis procedure.

At this stage of the examination procedure, a working hypothesis related to the structure (joint, neuromeningeal, nerve root compromise, etc.,), the segment(s), the 'stage', the 'stability', the 'irritability', precautions/contraindications, and the expectations of treatment outcome should be made. At the end of the subjective examination but prior to the physical (objective) examination a precise working hypothesis may be made as to what the physiotherapist expects to find during the physical (objective) examination. Maitland considers the subjective examination to be 70% of the examination process, with the remaining 30% of the examination process being divided into 20% for the physical (objective) examination and 10% for the treatment outcome (Maitland 1986).

During the physical (objective) examination a correlation to the findings in the subjective examination should be confirmed. This confirmation between the subjective and physical (objective) examination should include the relationship between the pain(s), the active movements which are compromised, the irritability of the disorder, the presence of neurological signs and symptoms and the confirmation of precautions/contraindications. The objective examination should confirm the presence of an 'opening' or 'closing' pattern of pain and movement dysfunction and it should confirm the existence of one or more regions of pathology. In the presence of more than one region of pathology the physiotherapist may need to identify whether the one movement is placing stress on 2 different structures and resulting in 2 different pains or whether this one movement is placing stress on 1 structure which is referring pain into a second region. This relationship of pains in the physical examination (objective) should correlate with the 'irritability' and the relationship of pains established in the subjective examination (i.e. body chart; aggravating/easing factors; onset of pains with respect to the past and current history).

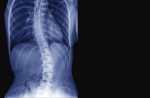

Within the physical (objective) examination a correlation between active movement dysfunction and Passive Accesssory Intervertebral Movement (PAIVM) and Passive Physiological Intervertebral Movement (PPIVM) may be made. The PAIVM may establish the segment(s) of dysfunction and the relationship of pain and resistence. Reassessment of the active movement after PAIVM may establish whether this technique had any effect on the most 'comparable' active movement dysfunction. Further, PAIVM's should help confirm or deny the relationship between the pain(s). The PPIVM may be correlated to the PAIVM's as to where the movement dysfunction(s) are/is taking place (e.g 2 segments within the cervical spine, 1 segment in the cervical spine and 1 segment in the thoracic spine and another in a peripheral joint). Further, PPIVM's may confirm the presence of an 'opening' or 'closing' pattern to the movement dysfunction (e.g. contralateral rotation may correlate with contralateral lateral flexion, lateral glide and flexion in an 'opening' pattern whereas ipsilateral lateral flexion may correlate with lateral glide and extension in a 'closing' pattern). Reassessment of the active movements after the PPIVM's may establish the validity of using this technique in the treatment of movement dysfunction due to pain.

Manual examination is a cornerstone of the manipulative physiotherapist's physical diagnosis of spinal joint dysfunction (Jull, Treleaven, Versace 1994). The manipulative physiotherapist's ability to detect the pathological segment in patients with spinal pain have been found to be reliable when tested against nerve and facet blocks, provocative discography, mobility X-rays and ultrasound scanning of acute segmental muscle spasm and inhibition (Behrsin & Andrews 1991; Hides, Stokes, Saide, Jull, Cooper 1994; Janos & Ray 1992, Jull, Bogduk & Marsland 1988). Jull et al (1994) suggest that the manipulative physiotherapist is able to determine the segment of pathology without reference to the patients pain, however the investigations by Maher & Latimer (1992) and the literature review of the neurophysiological mechanisms of pain (Zusman 1994) suggest that any "abnormal quality of resistance to motion" (Jull et al 1988) should be related to the patients pain.

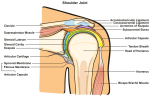

Special tests may need to be carried out in order to establish the presence of decreased neural tissue mobility (Butler 1991; Edgar, Jull, Sutton 1994; Elvey 1986; Selvaratnam, Matyas, Glasgow 1994; Yaxley & Jull 1991). Neural mobility may be a useful treatment and/or reassessment tool but should correlate with findings in the subjective examination as well as with the findings of the remaining objective examination (e.g. contralateral lateral flexion results in the pain, anterior palpation of the cervical spine (e.g.C5) results in the pain, and lateral gliding (C5) as well as lateral flexion (C5/6) are restricted in opening, then the mobilisation of any one of these components which improves pain and hence range of movement may improve the pain and range of movement in the other components, including the C5/6 component of neural mobility). Futher special tests to assess aspects of the subjective examination may include tests of instability. Insufficiency of the vertebral artery needs to be assessed in the patient complaining of vertebral artery symptomatology (e.g. dizzyness, ringing in ears, pins and needls on face and/or tongue, blurred vision, etc) and prior to manipulation . A neurological examination needs to be carried out in all patients who complain of spinal and peripheral symptoms extending beyond the hip and shoulder. If the patient complains of cord compression symptoms (e.g. bilateral pins and needles in both hands and feet and/or unsteadiness of gait) then the neurological examination needs to include the examination of the babinski reflex and clonus. Cauda equina symptomatology includes frequency of micturition and/or loss of bowel control and is considered a medical emergency. Therefore, special tests may be used to confirm certain aspects of precautions/contraindications in the subjective and physical (objective) examination.

Additionally, muscle energy techniques as propagated by the late David Lamb and Diane Lee of Canada should be used to assess muscular contributions to altered form and force closure around the pelvis, hips, thoracic and lumbar spines. The role of reflexogenic muscle spasms can also be assessed using dry needling techniques. These techniques should have an immediate affect on the PAIVM's and PPIVM findings as well as improving impairment measures associated with the disability. In upper quadrant pain, the role of the cervical and thoracic spine should be related to scapula function. Additionally, the role of lateral diaphragmatic breathing needs to be assessed in terms of scapula support, as well as abdominal-lumbar stabilisation and abdominal-lower limb blood flow due to it's affect on oscillatory iliopsoas function. Previous and/or current lower limb injuries need to be assessed in terms of inverse dynamics and the influence of impairment on disability. The role of eye dominance may need to be interpreted in relation to powerful occulomotor reflexes which can affect posture as well as influence feed-forward CNS predictive timing. Exercise prescription should have a direct correlation with improving the components of impairment needed to affect the disability and hence can be used as part of the clinicians reasoning process. Thus an integrated approach focusing on the clients goals using the cognitive structure of clinical reasoning can be used in every clinical presentation.

Clinical examples of this approach can be found through the following links

Explanations and References

Manual Therapie in der Behandlung von Schmerzen (Deutsch)

Terapia Manual y dolor (Castellano)

Tratamento do dor e inflamacao com fisioterapia manipulativa (Portuguese)

Manual therapy in the treatment of pain and inflammation (English)

Exercise and the Immune System (English)

Exercise and Sarcopenia (English)

Case Studies : Examples of the assessment process for clinical reasoning

Beispiel von Klinisches Denken (German)

Clinical Reasoning Exercise for low back and lower Limb (English)

Clinical example of treatment for functional instability and radicular LBP (English)

LBP Treatment Progress (English)

Clinical Reasoning Exercise for Neck-Upper Limb (English)

Apresentacao Clinica e Perguntas

(RACIOCINIO CLINICO) (Portuguese)

Presentation at the conference in Rome in October 2005 (English)

In conclusion, the Australian manipulative physiotherapeutic approach to movement dysfunction using manual therapy involves a clinical reasoning process of collecting information, interpreting this information, and forming multiple working hypotheses. By using the correlation of information it should be possible to narrow the focus of the therapists working hypothesis so as to be able to make a treatment decision. Even at the stage where a treatment decision has been made, the technique itself needs to be assessed in terms of its effect on the subjective examination and on the active movement dysfunction and hence disability. The therapist should also be able to make a decision as to the prognosis and expectations of treatment outcome. If these treatment expectations are not fulfilled, a change of treatment technique may need to be made. In this manner the therapist remains open minded and treats the clinical signs and symptoms based on a clinical reasoning process rather than treating an all-encompasing diagnosis or biased theoretical construct.

References

Behrsin, J., Andrews, F., (1991). Lumbar segmental instability : Manual assessment findings supported by radiological measurement (A case study). Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 37, 171 to 173.

Bogduk, N, Marsland, A., (1988). The cervical zygapophysial joints as a source of neck pain. Spine,

Bogduk, N., Twomey, L.T., (Eds.) (1991). Clinical anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. Churchill Livingstone. Melbourne.

Butler, D.S., (Ed.) (1991). Mobilisation of the Nervous System. (1st. ed.). Churchill Livingstone. Melbourne.

Edgar, D., Jull, G., Sutton, S., (1994). The relationship between upper trapezius muscle length and upper quadrant neural tissue extensibility. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 40(2), 99-103.

Elvey, R., (1986). The investigation of arm pain. In : Grieve, G., (Ed.). Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column.. Churchill-Livingstone. Edinburgh. 530 to 535.

Hides, J., Stokes, M., Saide, M., Jull, G., Cooper, D., (1994). Evidence of lumbar multifidus wasting ipsilateral to symptoms in patients with acute/subacute low back pain. Spine, 19, 165 to 172.

Janos, S., Ray, C., (1992). Mechanical examination of the lumbar spine and mechanical discography/facet joint injection. Proceedings of the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapists 5th International Conference, Vail, Colorado, A92.

Jull, G., (1987). Prove it or lose it. Proceedings of the 5th biennial conference of the Manipulative Therapists Association of Australia. Melbourne, 351 to 358.

Jull, G., Bogduk, N., Marsland, A., (1988). The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophysial joint pain syndromes. The Medical Journal of Australia, 148, 233-236.

Jull, G., Bullock, M., (1987). A motion profile of the lumbar spine in an aging population assessed by manual examination. Physiotherapy Practice, 3, 70 to 81.

Jull, G., Treleaven, J., Versace, G., (1994). Manual examination: is pain provocation a major cue for spinal dysfunction ? Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 40(3), 159 to 164.

Lee, M., Esler, M-A, Mildren, J., Herbert, R., (1993). Effect of extensor muscle activation on the response to lumbar posterior anterior forces. Clinical Biomechanics, 8, 115 to 119.

Lee, M., Svensson, N., (1990). Measurement of stiffness during simulated spinal physiotherapy. Clinical Physics and Physiological Measurement, 11, 201 to 207.

Maher, C., Latimer, J., (1992). Pain or resistance - the manual therapists' dilemma. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 40(3), 159 to 165.

Maitland, G.D., (1988). Manipulative Physiotherapy course : Bad Ragaz. (personal communication).

Maitland, G.D. (Ed.) (1991). Peripheral Manipulation. (3rd. ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. London.

Maitland, G.D. (Ed.). (1986). Spinal Manipulation. (5th. ed.). Butterworths. London.

Yaxley, G.,A., Jull, G., (1991). A modified upper limb tension test. An investigation of responses in normal subjects. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 37, 143 to 152.

Zusman, M., (1994). The meaning of mechanically produced responses. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 40 (1), 35 to 39.