Understanding constructivism (learning through clinical reasoning) through the deconstruction of competencies required for map reading in Orienteering

by Martin Krause (1988, 2007, 2013 and 2021)

Experiential learning, can occur, in the clinical setting. However, purely being there, without reflective thinking or application of knowledge, will not result in becoming a better clinician. Similarly, in orienteering, the participant can improve their map reading and decision making through reflection and analysis. In both scenarios, being physically competent isn't sufficient, without being cognitively proficient. The following discusses and illustrates the interesting parallels of learning, through the process of clinical (inductive and deductive) reasoning, with what is required for improvement in orienteering, map reading and decision making. Construction of knowledge, access and application, is a process of interaction, between individuals and specific to the environment in which they occur. As a clinician, philosophical constructs of improved existentialism, may ensue. As an orienteer, an improved process of clarifying, accessing, prioritising and using knowledge can be acquired through the deconstruction and reconstruction of the competencies required for the tasks demands.

An abridged timeline of learning through constructivism

- "The human mind can know only what the human mind has made" i.e. knowledge as constructed by the individual (Giambattista Vico 1725)

- “Reflection is a meaning-making process that moves a learner from one experience into the next with deeper understanding of its relationships with and connections to other experiences and ideas. It is the thread that makes continuity of learning possible" (John Dewey 1910)

- “Complex thinking begins the unification of scattered impressions; by organising discrete elements into groups, it creates the basis for later generalizations.” (Lev Vygotsky 1934)

- Piaget publishes The Origins of Intelligence in the Child, positing that knowledge is restructured (accommodated) when the learner faces a disequilibrium, or a situation that cannot be solved with an existing schema (assimilation). Constructivism is considered, with knowledge construed, as structures/schemas, constructed to adapt to dilemmas, in the learner's environment.(Piaget 1936)

- Dewey suggested that experiences that compel the learner to move forward to new experiences (continuous), and can satisfy the internal needs of the learner (interactive). Thus, experience can be seen as an opportunity for the individual to learn more through the experiential process, establishing a new and relevant situation, an experience that modifies both the learner and the context of his/her relationship to the environment.(John Dewey 1938)

- Bartlett publishes Thinking: An Experimental and Social Study. His 'story completion' experiments give support to the unconscious process of adding existing knowledge to new, incomplete situations. His work "sheds light on how schemas, as a way of organizing past experiences, lead one towards constructive and predictive processes”.(Sir Frederic Bartlett 1958)

- Bruner explores Discovery Learning in The Act of Discovery for the Harvard Education Review. He describes what he calls cumulative constructionism. This process finds the learner stringing together previous knowledge to construct viable solutions to problems or dilemmas. This is counter-posed to episodic empiricism, which finds the learner juggling disparate knowledge and information in a disorganized, haphazard attempt to make meaning of the dilemma.(Jerome Brunner 1961)

- Kolb and Fry author Towards and Applied Theory of Experiential Learning in G. Cooper, Ed. (1975) Theories of Group Processes. New York: Wiley Kolb and Fry suggest that learning is an iterative process of experience, reflection, and reaction, that "learning is best facilitated in an environment where there is dialectic tension and conflict between immediate, concrete experience and analytic detachment."

They suggest that the learner will adopt a learning style (Diverging, Assimilating, Converging, Accommodating) that reflects her/his resolution of ways of relating to their experience: Concrete Experience vs. Abstract Conceptualization and Active Experimentation vs. Reflective Observation.(David Kolb and Ronald Fry 1975) - Cognitive restructuring occurs continually as the organism (learner) interacts with and responds to environmental changes, or perturbations.(Humberto Maturano 1978)

- Jack Mezirow (1978) an interesting concept of meaning-making. He suggests that when a learner confronts a dilemma that her existing knowledge cannot accommodate, and altering existing structures does not help, she encounters a disequilibrium in her perception of the environment. This requires a fundamental and critical examination of her own beliefs, attitudes, and dispositions. Any resultant realignment of these beliefs to regain alignment with the environment is akin to a Kuhnian paradigmatic shift, a transformation of perspective. Mezirow suggests: “a conscious recognition of the difference between the old viewpoint and the new one and makes a decision to appropriate the newer perspective as being of more value.” (Transformative Learning)

- Flavell coins the term "metacognition" in his article for American Psychologist entitled. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Flavell defines metacognition as, "one's knowledge concerning one's own cognitive process and products or anything related to them." He postulates two aspects of metacognition: 1. metacognitive knowledge about how individuals (including the learner) learn, and 2. metacognitive regulation. Metacognitive regulation comprises the cognitive activities of the individual pursuant to accomplishing the cognitive goal : "thinking about thinking." (John Flavell 1979)

- Morin's first volume of Méthode introduces his concept of Complex Thought. Although not strictly an invocation of Complexity Theory, Morin extrapolates his views of Complexity Theory to conceptualize knowledge as an interdisciplinary melding of otherwise soloed or paradigmatic schemas of knowledge. Knowledge that is pertinent is not bound by area of study, rather it should be conceived of as emerging from the interrelationships among various fields of study. Morin's theorizing sows the seeds of Complexity Theory as a lens to how knowledge is constructed. (Edgar Morin 1981)

- Candy (1991) publishes Self-direction for lifelong learning: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice. Candy positions his views within constructivism, writing: "Learning consists of the construction of personal meaning and the assimilation of new information, attitudes, and skills into the existing framework of personally meaningful constructs" (1991: xix).

He then posits that life-long learning needs to be seen as both institutionally housed as well as emergent in the learner's life experiences. He suggests self-directed learning comprises:

1. interaction among learner and their environment

2. socially-constructed, iterative adaptations

3. qualitative reinterpretations of phenomena

4. interdependent social relationships among learners and the characteristics of and within their environments

This presages the concept of independent learners situated within connected environments.

https://www.cognitiveconstruction.com/cognitive-building-blocks/constructivist-timeline/

Index

Introduction

Orienteering involves complex decision making using multiple variables of information to ascertain the optimal path. Clinical reasoning is a similar balance of gleaning the right amount of information to build a clinical picture. Too much information and we have information overload, whereas with too little information, we again arrive at an impasse, with the likelihood of making mistakes, such as 'confirmation biases'. Information optimisation, in the form of clinical reasoning, and deductive reasoning, in particular, is a process of confirming expectations through the process of questioning and examination. When expectations aren't realised, then the therapist must revert to inductive reasoning, which requires problem deconstruction back to first principles, to rebuild a clinical picture, which makes sense and in turn provides a solution, both to the client and anyone else, who ask for face and construct validity, for the evidence of efficacy of treatment. When reading a map in a sport like orienteering, it is important to read the map ahead of where you are going, so that when the runner comes to the terrain they are confirming or negating their expectations. There is a positive correlation between motor performance and map reading skills. That is, the feedforward mechanisms of motor control are more finely tuned, when the runners map reading skills, are similarly, more finely tuned. Importantly, in order to optimise cognitive performance, the information on the map, needs to be simplified, into meaningful small chunks of information. The following are map reading exercises for the development of competency in orienteering. By de-constructing various elements of map reading, greater competency can be obtained. Additionally, physiological variables can also be manipulated to enhance cognitive skill. Ultimately, improved feed-forward predictive reasoning skills should be accomplished. Whilst running through the forest, it is very rare for an injury to occur, when the cognitive processing is optimal. Similarly, in the clinical situation, the more finely tuned the predictive reasoning skills are, the less likelihood of getting lost during the examination resulting in a mis-diagnosis. Additionally, by making predictions throughout the clinical reasoning process, scientific credence, is given to the process of examination and re-examination, whereby variables are defined, included and eliminated. The predictive validity of testing becomes the clinicians 'null hypothesis'. In orienteering competitions, economy of movement and information processing capacity, are reflected by the fastest time as the metric of choice; whereas in the clinic, it is the minimal intervention which derives the maximal and most optimal outcome which should define the economic value of the health intervention.

Context

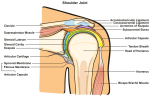

When reading a map, a rock is a rock, however the identification of features on how to find the location of the rock will be different if it is in a Siberian birch forest on the side of a Japanese mountain, a Baltic pine forest in Europe, beech forest in New Zealand or Eucalyptus forest in Australia. What is the significance of a rock in a boulder field and how does the topography of the landscape contribute to finding the correct rock? Similarly, the features associated with a supraspinatus shoulder problem will be different in an elderly person, an office worker and a freestyle bouldering rock climber. What are the salient clinical features which make the supraspinatus significant in the presence of multiple pathology from shoulder, neck and rib cage trauma/dysfunction? In all cases, it is the context which drives the analytical process of reducing the problem to the most significant variables in order to construct a picture which achieves the desired outcome.

Map reading

Looking for check points (controls) in a given area based on all aspects (variables) of map reading and the control descriptions

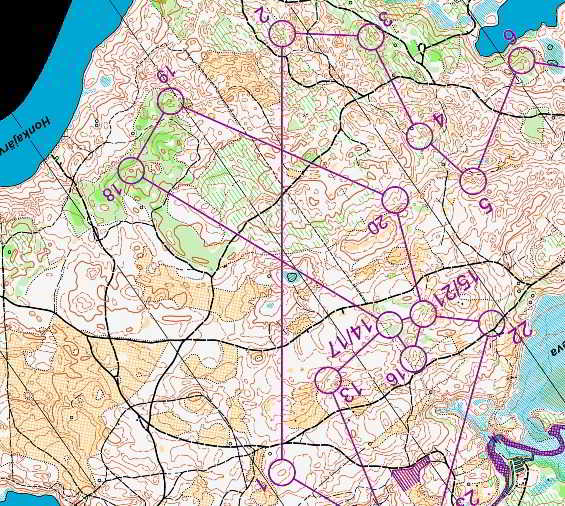

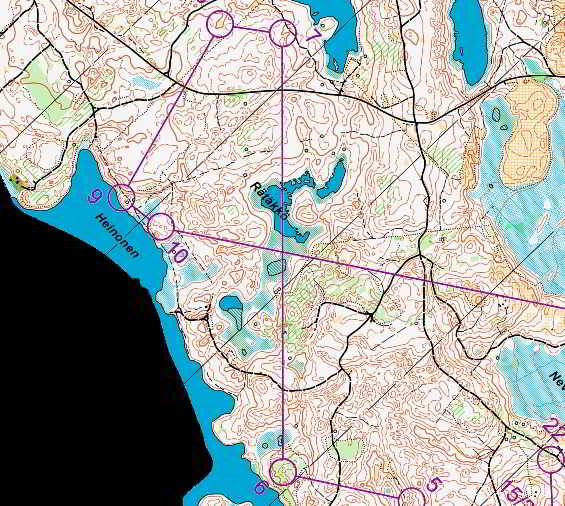

The following is a typical Swiss orienteering map. Information contained within, include contours, tracks, vegetation types and their boundaries, rocks, cliffs, and water courses. The aim of competitive orienteering is to following the course in a sequential manner and post the fastest time against the clock and hence your fellow competitors. Following one another is considered immoral and against the spirit of the sport. Not only does the competitor need to be physically fit, they need to make the optimal decisions on which way is going to be the fastest between each of the check points (controls = orange and white flags with an electronic recording system). The course setter provides challenges to the competitor, which need a solution.

, Click on each map if you would like larger detail.

The above is the original map - the next 3 maps are variations on the original

The above is the original map - the next 3 maps are variations on the original

Multiple options and multiple solutions, similar to the clinical reasoning scenario seen in musculoskeletal physiotherapy.

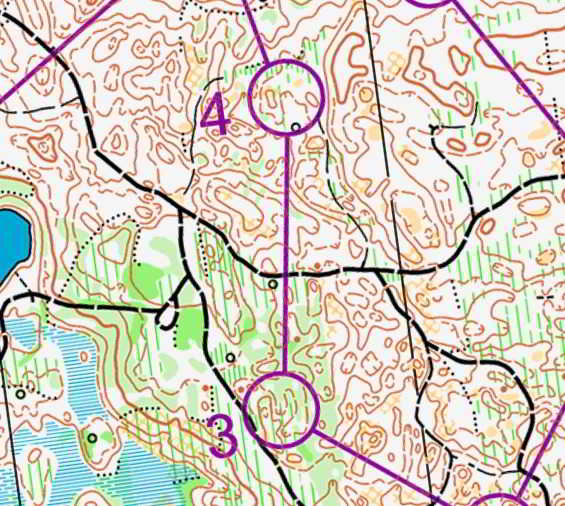

Track orienteering - relatively simple correlation of a track network with 'sense of distance' and control description.

To take the track or is it faster to go through the bush. Here, the objective, of the training, is to force the athlete into a form of orienteering and thinking, which might not be the natural solution, when it comes to the real event.

In the clinical reasoning scenario, the novice musculoskeletal physiotherapist may look for the easiest solutions to the problem presented. The questioning of the patient may take on a rote learning style routine, with little variation from text book process. Neither deductive nor deductive reasoning is employed and a set script or protocol might be applied. Outcomes are still assessed but optimal methodology may not have been applied. Never-the-less, as long as outcomes are measured this is frequently a safe way to manage a simple problem. It can also be a 'jumping off' point to the next level of cognitive function and hence clinical reasoning complexity.

Clinically, keeping the diagnostic process too simple may lead to errors. A clinician may place all the wait of their diagnosis on the results of imaging. Yet the 'false positive' rates of imaging are 48-52%, meaning that 48-52% of asymptomatic people will have pathology on imaging of the shoulder, knee and low back. In the absence of a gold standard of testing. imaging results should be taken, in the context of 'correlations' within the entire interview and examination process. (https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/latest-news/245-imaging-2.html)

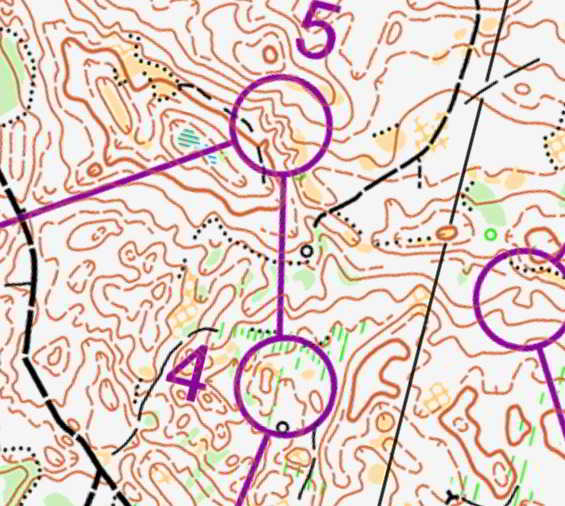

Compass orienteering - only variables are distance and compass bearing

This is a very important and somewhat difficult skill in sloped terrain. Taking a compass bearing is easy, staying on that bearing can be hard. During the 'flight in the forest', sure footedness is important, but staying on course, by checking (correlating) the features in the forest with the map, along the corridor being followed' becomes equally important, in order to determine that the compass bearing is still being followed.

In the clinical reasoning process, a particular working hypothesis might be followed. Deductive reasoning, like the compass bearing, requires confirmation of the presenting signs and symptoms for a diagnosis to be made and a management strategy to be instigated. Naturally, like following a narrow corridor in orienteering, during clinical reasoning, this can lead to 'confirmation biases' and lack of alternative thinking. It may also represent just one solution, where there may be many, and hence may not represent the optimal solution, even though the desired outcome may have been achieved. Assessment, treatment and reassessment of the presenting features become an ongoing cognitive - metacognitive spiralling process.

Philosophical constructs of existentialism and the spiral vortex

Existentialism is a philosophical term which accepts a reality which can be described in linguistic terms. The mere presence, in German, 'da sein' (Heidegger) or in French 'Raison d'être' - reason for being, has been described as not accepting things at face value but transcending the passiveness of 'acceptance and inaction' to one where a persons actions create a new level of consciousness and understanding. In Franz Kafka's work 'The Trial' Herr K is put on trial, where his only defence was that it was absurd that he was on trial. French school children are taught in terms of the upward spirals of knowledge and existence. Knowledge building upon knowledge and standing on the shoulders of giants to see further than giants.

As ‘re-volution’ or ‘re-evolution’, the spiral progression is symbolic of the transpersonal route to that higher level of consciousness which is sought by all esoteric and occult systems. Paralleling these inner movements of the psyche which indicate the transformative and the integrative are movements in physical space: the vortex, or involution, representing an opening or re-awakening; the circumambulatory, as utilised in mazes and labyrinths; and oscillation, the movement back and forth between dualities. The circumambulatory and oscillatory suggest the mandala, a symbol of wholeness, while the spiral and the vortex point to dynamic growth and metamorphosis.

Blind Compass orienteering - as hard as it gets. Only 1 variable and hence no correlations with other information is possible

This is forcing the athlete into just one solution. A lot can be gained with this form of training. On the upside, the technique itself can be perfected and additionally, the pitfalls or relying on just one piece of information is exposed. However, features within the corridor can still be 'ticked off' along the way.

In the clinical reasoning process, a therapist may find that a particular technique works exceptional well, but does it really work that well for all scenarios, if more information determined.an alternative technique or treatment methodology. Narrow view, narrow alternatives and narrow outcomes, with a huge potential of getting lost on the way.

Straight is great or is it really?

The straight line is shorter, but maybe technically (cognitively) and physically more demanding, however, going around is a faster km rate. How far off the straight line is too far?

In clinical reasoning, it may be cognitively less demanding to do a technique which is easier such as trigger point massage, but the cognitively more demanding dry needling technique may have a faster effect and allows simultaneous use of joint mobilisations and exercises. From novice to expert, each to their own, so long as each experience is reflected upon, monitored for outcome and learned from, as a transformative experience, for the next clinical reasoning scenario. Other examples may be the use of joint mobilisations around the hip and lumbar spine versus the more demanding muscle energy techniques. One can use analogies only to a certain point, yet, never-the-less they can be useful to illustrate a paradigm or construct. Transformative learning encourages paradigm shifts within a certain context or environment..

Contour only

Contour only orienteering training can be particularly useful, as the tracks are removed, thereby removing a simple solution. Forcing, higher cognitive thinking, makes the athlete perform mental gymnastics, which they could be unfamiliar or insecure with. Additionally, it makes the athlete run through the terrain, thereby increasing their agility, balance and strength.

Higher physical and cognitive demands improve the athletes competitiveness. Clinically, a physiotherapist can deliberately use new and novice techniques, in place of old, tried, tested and familiar methodologies, to enhance the scope of their cognitive and physical function. Alternative solutions, to familiar problems, may lead to a better way of managing certain 'clinical pictures' and/or highlight past 'confirmation biases' exemplified by 'closed' vs 'open' questioning, as well as the use of new techniques, which prove to be superior to old techniques or highlight a new variation of a 'clinical picture' where previous 'mindfulness' was missing. In clinical reasoning this mindfulness is referred to as 'meta-cognition' or thinking about your thinking. Verbalisation (discussion with client or other professionals) and visualisation (creating flow charts and algorithms) of ones thinking is a pathway to the subconscious, where 99% of our cognitive processing is occurring.

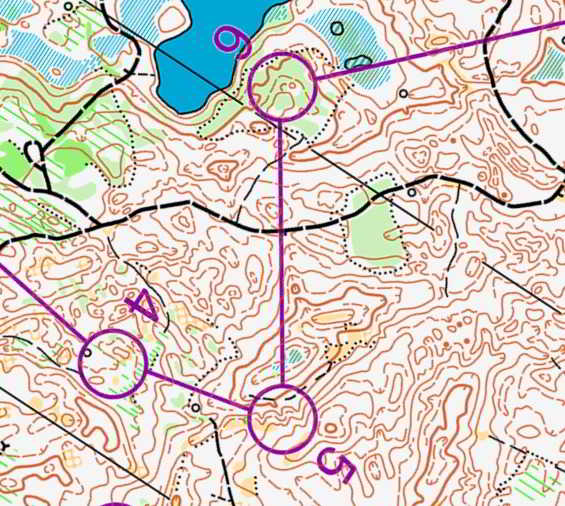

Map with tricky 'negative terrain'

Negative terrain is basically 'upside down orienteering'. Normally, we look at contours as hills rather than holes......and no one wants to fall into a hole.

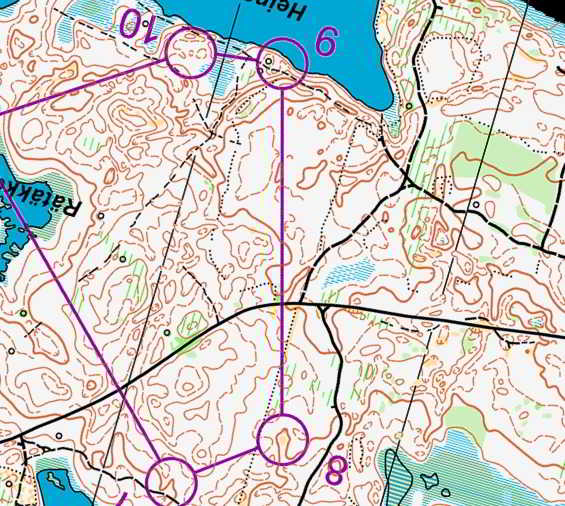

An interesting loop relay event, where several different courses were run in parallel, with some common controls, in highly tricky, negative terrain. (Kaajani, Finnland 1989). Many controls were close to one another and hence it was important that the correct controls were being checked off. The physiological variable of increasing speed was correlated with the need for increased cognitive processing efficiency. That is, reducing each attack point to a clearly defined feature in the terrain, which would in turn immediately indicate the direction of the control flag, during which time it is important to commence reading the map for the following control. For example, start -> 1 : saddle, 1->2 small gully leading into depression - need to maintain height as control sits high between 2 depressions (note map had extensive 'negative terrain'), 2->3 small spur with small gully on right - exaggerated due to negative and positive terrain, 3->4 large clearing, 4->5 long gully with major depression on left parallel to line of run for control feature, 5->6 clearing and then large negative depressions, 6->7 off edge of semi cleared area and get direction correct - the control feature of a gully beyond high points should be obvious, 7->8 track, 8->9 contour around the very large depression, 9->10 semi cleared then track end then depression on left, 10->finish need to get direction correct before arriving at 10. Moreover, the runner has a mental image of the terrain before they arrive in the attack point area, where they should compare their conscious and subconscious expectations to what they see. Hereby, the imagery creates a path to the subconscious.

An interesting loop relay event, where several different courses were run in parallel, with some common controls, in highly tricky, negative terrain. (Kaajani, Finnland 1989). Many controls were close to one another and hence it was important that the correct controls were being checked off. The physiological variable of increasing speed was correlated with the need for increased cognitive processing efficiency. That is, reducing each attack point to a clearly defined feature in the terrain, which would in turn immediately indicate the direction of the control flag, during which time it is important to commence reading the map for the following control. For example, start -> 1 : saddle, 1->2 small gully leading into depression - need to maintain height as control sits high between 2 depressions (note map had extensive 'negative terrain'), 2->3 small spur with small gully on right - exaggerated due to negative and positive terrain, 3->4 large clearing, 4->5 long gully with major depression on left parallel to line of run for control feature, 5->6 clearing and then large negative depressions, 6->7 off edge of semi cleared area and get direction correct - the control feature of a gully beyond high points should be obvious, 7->8 track, 8->9 contour around the very large depression, 9->10 semi cleared then track end then depression on left, 10->finish need to get direction correct before arriving at 10. Moreover, the runner has a mental image of the terrain before they arrive in the attack point area, where they should compare their conscious and subconscious expectations to what they see. Hereby, the imagery creates a path to the subconscious.

During clinical reasoning, many features of a presentation, can be similar and yet not the same. Asking the correct clarifying questions or preforming a few more examination techniques may illicit better clarity to the presenting problem. However, extra questioning and extra examination techniques can take more time. Importantly, speed of thought occurs with precision in the choice of examination and treatment techniques.

Enhanced cognitive capacity at supra-anaerobic threshold

In this last scenario, there were several parallel courses and/or 'dummy controls. The objective was to run from the bottom of the hill up to the loop and repeat the exercise at least 4 times in a given period of time (e.g. 40 minutes). Ideally, the athlete preforms better on each loop, even though they should in theory be fatiguing. If the loop is the same then the cognitive demands should reduce on each loop, whilst the physiological demands are increasing. The concept involved the use of anaerobic threshold cognitive capacity. At an elite level we demonstrated that at least half of the Swiss elite orienteers could concentrate better at supra-anaerobic threshold. Unfortunately, Dr Toni Held's thesis, on this phenomenon, was never published as it went against the consensus of the time. Since, early this century, researchers have come to recognise lactic acid is an important fuel for aerobic-anaerobic exercise through the production or conservation of the energy substrate, pyruvate, via the Ciori cycle in the liver. The pathways of lactic acid metabolism probably depend upon the internal metabolic conditions when exercise stops. High levels of lactate and slightly reduced levels of other substrates such as liver glycogen and blood glucose appear to favour lactate oxidation to pyruvate, thus saving some glycogen; whereas, the effects of prolonged exhaustive exercise may favour lesser oxidation and greater conversion to glucose. Thus lactate is an important reservoir of carbon energy during recovery (Brooks et al 1999, Exercise Physiology : Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications; Mayfield Publishing). In this case, the downhill running was the recovery phase, even though it was at maximum speed, but the soft ground also allowed for maximum efficiency of elastic recoil in the bounding muscles.

Discussion

The previous discussion revolves around map reading, the reduction of variables and the use of this reductionist approach to become self-aware of strengths and weaknesses in different information biasing scenarios in the same terrain. Similar exercises should be done in various terrains, to help the orienteer determine which strategy is best for which terrain or more importantly, which combinations of variables optimises the decision making cognitive processing to determine the best strategy. Also, which predictive reasoning variables from the map can be used as 'checks and balances' in determining that the runner is still going in the correct direction. By using these meta-cognitive strategies the runner can reflect on the reasonableness of their biases which weigh more heavily in their reasoning. It is important to remember that 99% of our cognitive processing occurs at the subconscious level. Through verbalisation and visualisation and using strategies such as predictive reasoning we can gain access to our subconscious. Ultimately, the runner wants to run efficiently and cleanly to the control without cognitive overload. Flowing through each and every control in an effortless manner until the finishing line is the ultimate 'da sein'.

Using the analogy of the orienteer running through the terrain, we can examine clinical reasoning or 'the unbearable lightness of being' in a similar way. In the forest the runner wants to come across features in the terrain which ultimately leads them to their destination. Clinically, the practitioner wishes to do the same thing. During the 'subjective' examination, questions are asked to confirm or negate the 'working hypothesis'. Whilst during the 'physical' examination, tests are carried out and treatments undertaken and signs and symptoms are assessed and reassessed to confirm the diagnosis as well as create a prognosis. During this entire process 'feed forward' predictive reasoning mechanisms are being put in place which act as 'checks and balances' that attain the desired outcome, which is the amelioration of suffering and the improvement of impairments.

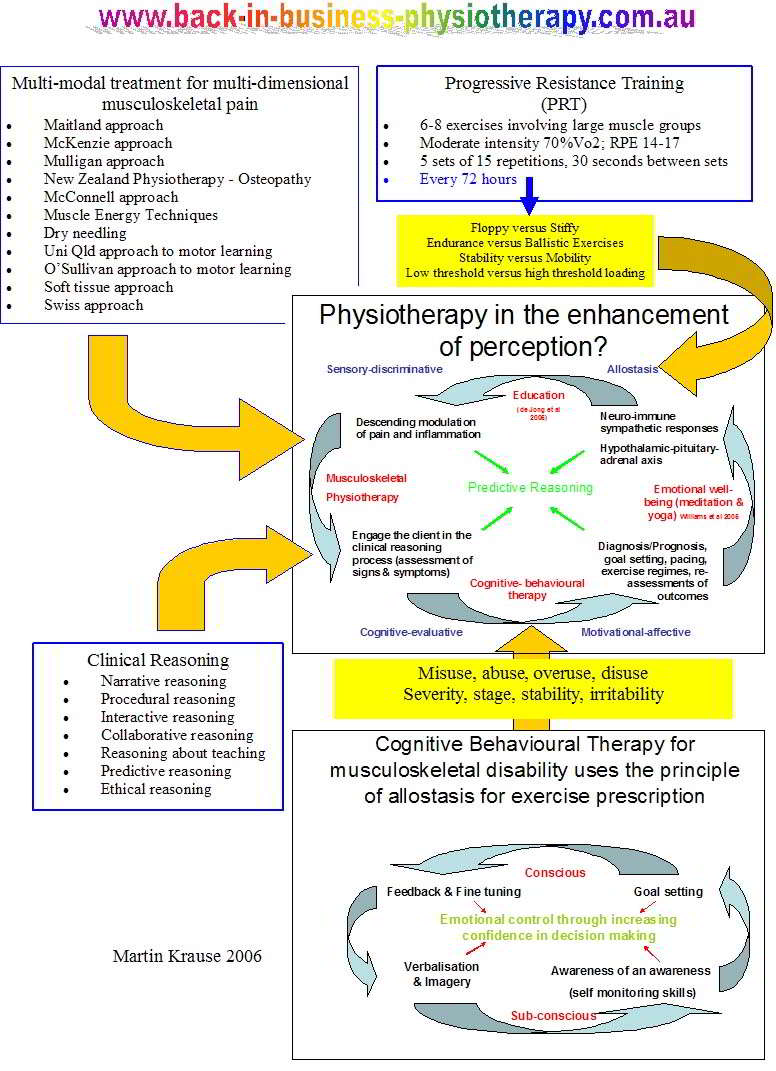

The map for clinical reasoning may look like the following (taken from the Maitland concept), whereby a structured process of deductive reasoning allows the organisation of knowledge retrieval, to take place, whilst creating a mechanism for the correlation of information. Clinical pattern recognition reflects the storage of the correlated information into meaningful chunks. Clarification and refining of information is what is referred to as inductive reasoning. When pattern recognition doesn't take place, then the clinician needs to revert back to 'first principles' reconstructing information into a new clinical picture. Incorrect confirmation biases, and hence getting lost in the examination and treatment process, should be reduced by reflecting on the 'checks and balances' in questioning, so as to correlate these with differential diagnostic maneuvers, so that all aspects of the subjective and physical examination are covered in a precise and effective manner.

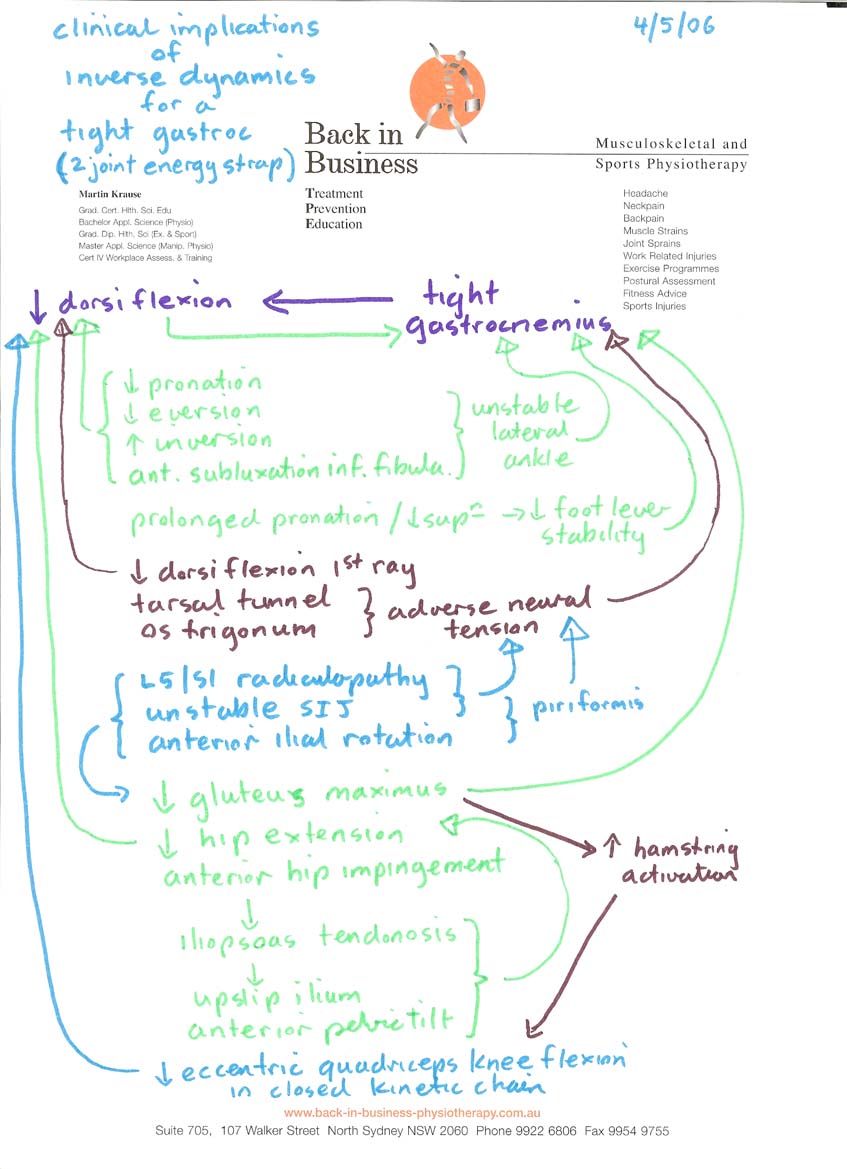

An example of multiple hypothesis formation for a tight calf and ankle problem. The mind map or 'flow chart' of cognitive 'null hypothesis' formation.

Conclusion

Just as the orienteer uses a map to develop a picture of the terrain ahead, the clinician also forms needs to form a picture of the expected clinical presentation from the narrative of questions and answers with the client. Hence, the features of the signs and symptoms create the picture. The narrative between the clinician and client, with the appropriate questions and reasoned explanations allow the conscious to access the subconscious where 99% of our cognitive processing occurs. The working hypothesis creates the scientific rationale by making a prediction. Further construct validity is attained by testing the prediction, through the reduction of the clinical variables. The correlation of the confirming and negating information also reduces the likelihood of making a mistake through confirmation biasing when using too few clinical features. Ultimately the power of the prediction is verified through successful clinical outcomes. Constructing a clinical picture through the correlation of all the significant variables is the ultimate objective of a successful outcome. Successful outcomes can then be laid down in the brain as a template, for quick recognition, in future use for a now familiar clinical problem. Similarly, in new terrain, the orienteer needs to consider the familiar and unfamiliar features and decide whether they need to revert to first principles of reasoning. By considering all the unfamiliar features, the cognitively more demanding short term memory and conscious processing comes into play, which deconstructs the problem, before constructing a map reading strategy using familiar features (eg compass bearing, contours), in order to arrive at the destination of unfamiliar new terrain. Hereby, the orienteer lays down new long term memories of successful navigational strategies (cognitive templates), to use at a later date, for a new but familiar terrain. In chess the laying down of sufficient 'cognitive templates' to attain expertise takes around 10 years of consistent cognitive effort.

Motor Learning in Orienteering

Mind maps and clinical reasoning

Instructional Design and Cognitive Processing

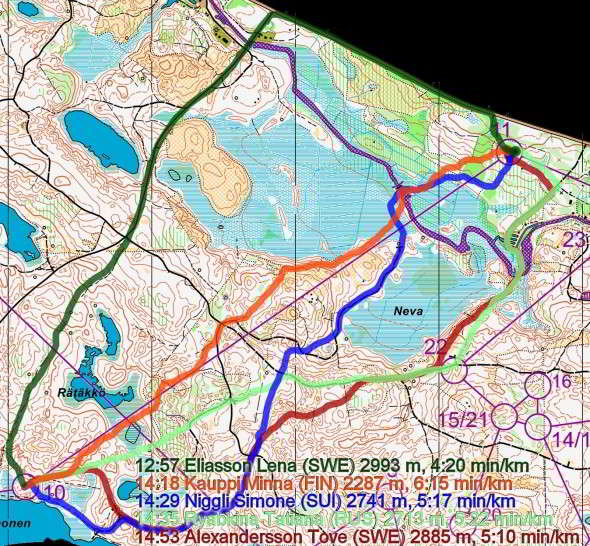

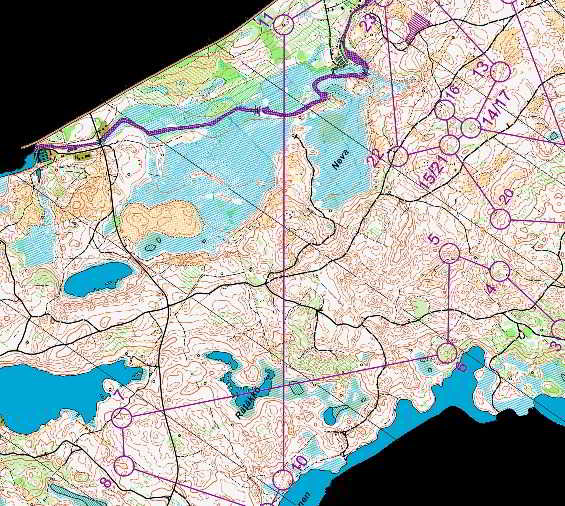

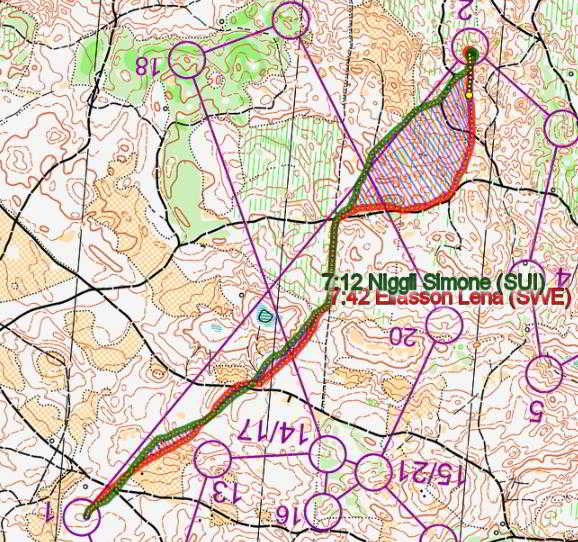

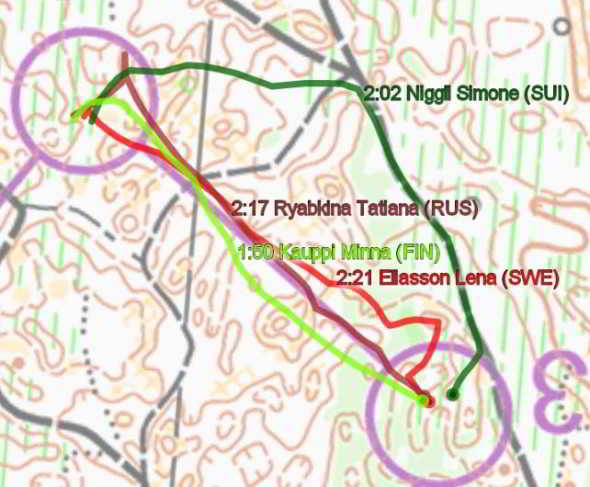

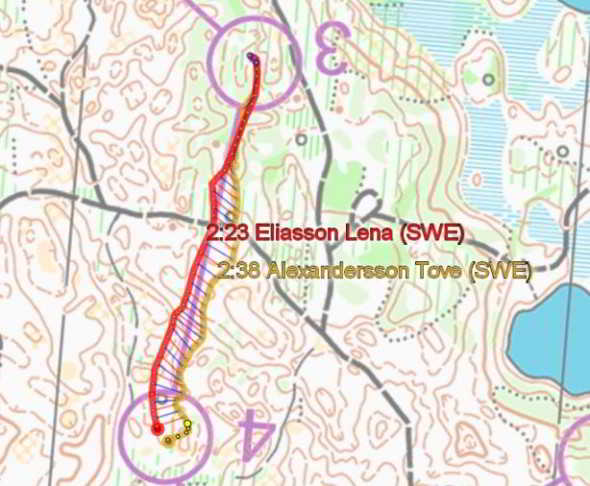

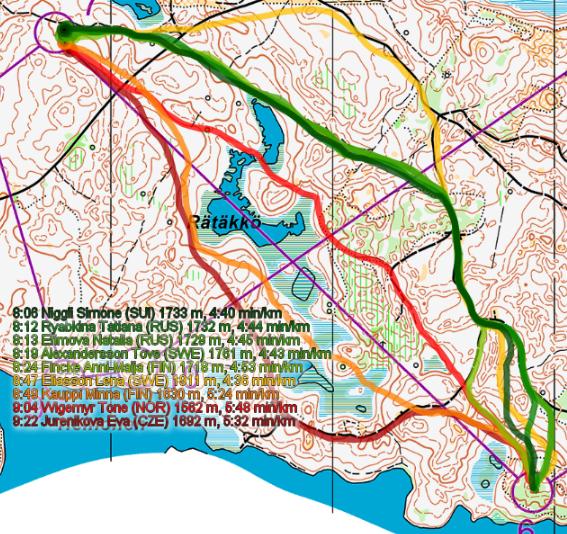

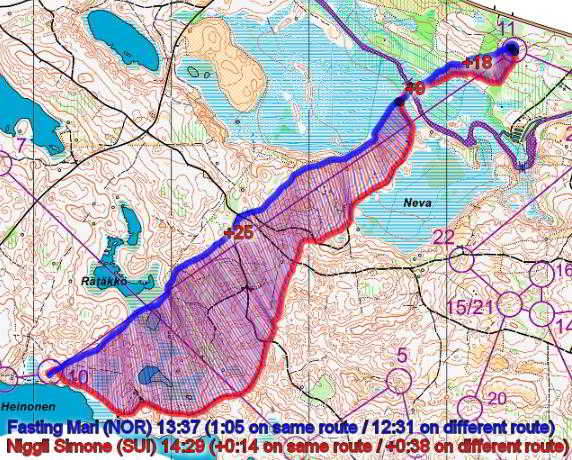

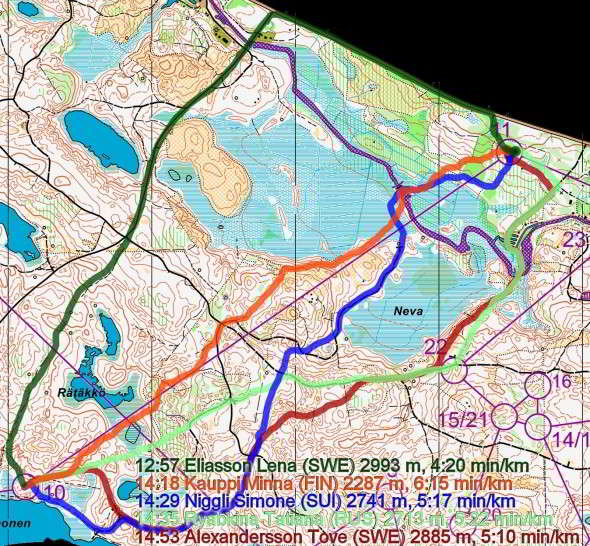

World Orienteering Championships, Vuokatti, Finland 2013

During the second week of July 2013, the world orienteering championships took place in the middle of Finland. This is a particularly important place for me, as it is where I started my professional orienteering physiotherapist - trainer career back in 1989. The following are a snap shot of maps with route choices and errors which occured amongst the worlds best.

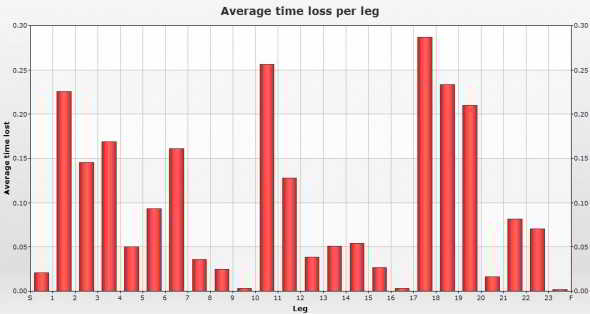

Errors, route choices and times lost

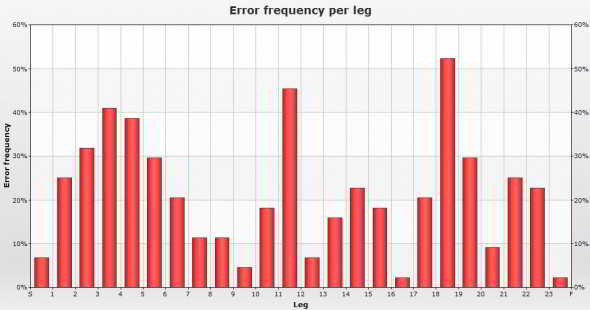

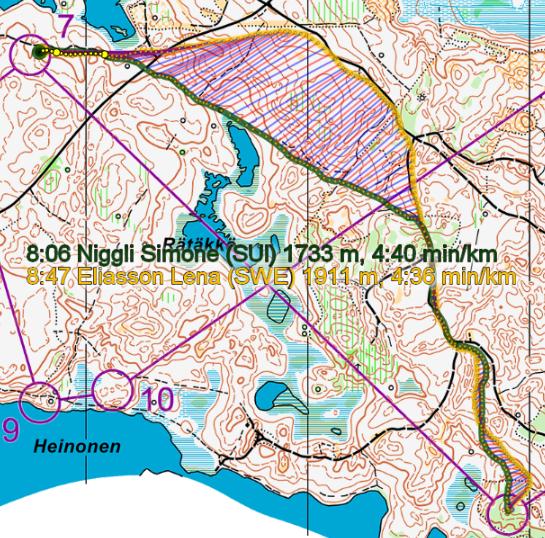

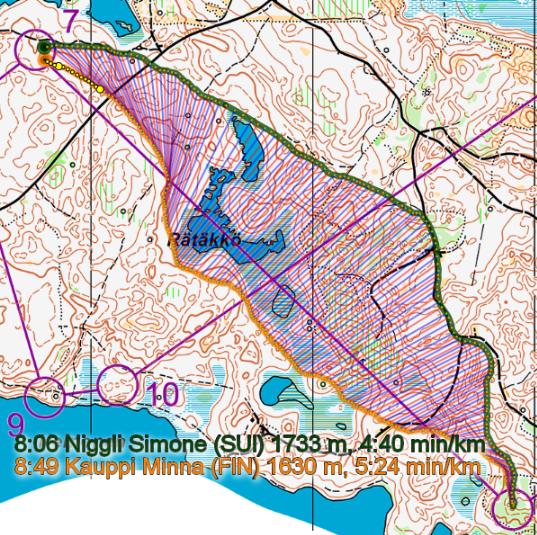

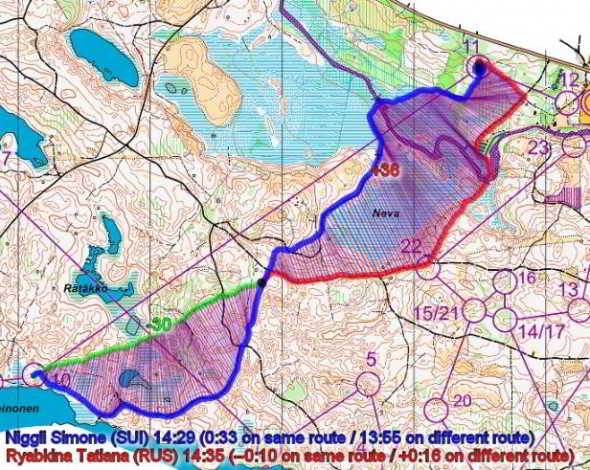

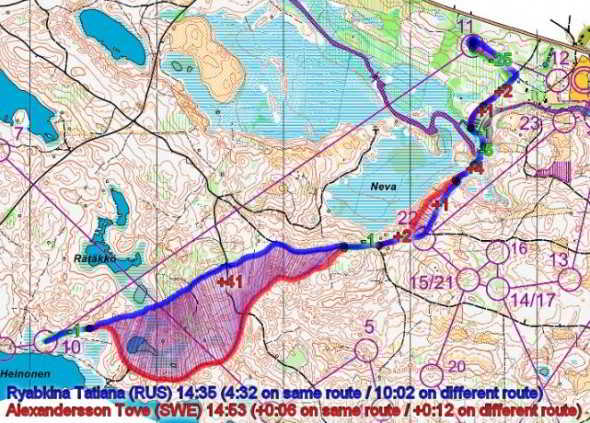

Comparison of route choices between competitors

The longer the leg, the greater the number of choices, correlates with, the greater the variability of success. Clinically, the longer the story, the greater or more complex the clinical picture, the greater the possibilities of intervention. However, similar to orienteering, the speedier the intervention, the more structured the cognitive processing, the sooner the improvements in signs and symptoms, the better the rate of success.

Uploaded 31 December 2006

Updated 21 August 2021

based on Orienteering exercises with OLG Chur and the Swiss National Team 1988 - 1993

WOC Vuokatti, Finland 2013

Training camp ; Swiss B Kader National Orienteering Team, Vuokattinhovi, Kajaani, Finland 1999