Rowing Injuries

Rowing is a highly repetitive strength-endurance sport. Results of the last few world championships have shown that the crews in the finals are finishing races closer together, indicating the increasing competitiveness of the sport (Kleshnev, 2008). This is partly due to increased participation rates all over the world, including more locally with record numbers of rowers racing in Rowing NSW regattas almost every year. Athletes and coaches are continually searching for ways to improve the performance of their crews (Nolte, 2005). Rowers can be men or women, school aged or masters (including over eighty-five years old), lightweights and heavy weights, scullers or sweep rowers, novices or elite athletes, and even coxswains. There is a place in rowing for athletes of almost all ages, dimensions and skill levels.

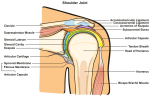

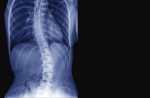

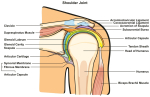

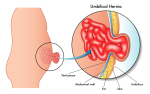

By comparison to other sports, rowing has virtually no traumatic injuries and has an impressively low injury rate, when looking at the time lost in competition due to injury. However, due to the repetitive nature of the sport and the high loads involved, there are some injuries. Rowing is a physically and technically demanding skill that requires the trunk to act as a transfer for large forces between the upper and lower extremities (Hagerman, 1984). Prevalence of spinal pain in rowers has been reported as high as 85% in elite rowers (Goodman and Hooper, 2008), making it the most common site of pain and injury in rowing (Reid and McNair, 2000; Hickey et al, 1997). Other common sites injured include rib stress fractures, forearm injuries and shoulder injuries (Hooper and Goodman, 2008). Minimising injury rates and having athletes return to training faster can obviously improve the performance of the crew.

It is well known that increased time spent rowing on the ergometer, as compared to rowing on the water, is associated with an increase in the incidence of low back pain. This led Rowing Australia in 2008 to change the ergometer trials from fixed to sliding ergometers, and this is now the standard across Australia. Rowing Australia also reduced the ergometer drag factors for the various divisions of athletes. Despite these positive changes, rowing on the ergometer remains very different in terms of the biomechanics to rowing on the water with more emphasis on the body swing than on water, and less emphasis on leg drive than on water (Kleshnev, 2005).

The biomechanics of rowing is vitally important for both performance and injury prevention. An APA Sports Physiotherapist familiar with rowing will be able to assess the rowers numerous important muscle lengths and strengths to ensure optimal biomechanics. It is estimated that rowing uses more than 70% of your total muscle mass (Steinacker et al 1998), which is far greater than most other sports. It is also important to view the athlete rowing, either on water by video footage or on the ergometer, and to liaise with the athlete’s coach to tailor the rehabilitation to suit the training phase and program.

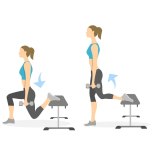

There is good news for rowers with low back pain coming from the research, with recent studies (Perich et al 2011) showing that one session per season of education by a physiotherapist, weekly leg and pelvis strengthening exercises and a weekly core stability session can reduce the incidence of in season low back pain in school aged rowers by 50%. Some of these strategies are probably already included in your school's rowing program, but with further research refinements can be made. For example, Kleshnev (2001) has shown that the principle of specificity applies to speed as well as action, when he showed that single leg press is more relevant to rowing than squats because of the speed of knee extension is more similar to on-water rowing in single leg press than squats.

The thorax plays a pivotal role in creating the leverage required for rowing. Thorax dysfunction including ' thoracic ring shifts' can dramatically affect the power output in both the arms and legs as well as play a major contributing factor in low back, neck and shoulder pain. Please see the thorax section elsewhere on this site for more details.

Martin Krause worked with the Swiss Olympic team rowers for the Barcelona Olympics back in 1992 and continues to have a keen interest in man-machine interface biomechanics.

1. Goodman and Hooper, (2008). “2007 Australian Rowing Teams: A Discussion of Illness and Injury Statistics.” Rowing Australia

2. Hagerman, (1984). “Applied physiology of rowing.” Sports Med 1:303-326.

3. Hickey, G. J., P. A. Fricker, et al. (1997). "Injuries to elite rowers over a 10-yr period." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 29(12): 1567-1572.

4. Kleshnev, (2001). Rowing Biomechanics Newsletter Vol. 1 No.7

5. Kleshnev, (2005). Rowing Biomechanics Newsletter Vol. 5 No.1

6. Kleshnev, (2008). Rowing Biomechanics Newsletter Vol. 8 No.90

7. Nolte, (2005). “Rowing Faster”

8. Reid, D. A. and P. J. McNair (2000). “Factors contributing to low back pain in rowers.” Brit. J. Sports Med. 34:321-322

9. Steinacker, J. M., W. Lormes, et al. (1998). "Training of rowers before world championships." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 30(7): 1158-1163.

10. Perich, D., A. Burnett, et al. (2011). "Low back pain in adolescent female rowers: a multi-dimensional intervention study." Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 19(1): 20-29.

Updated : 19 July 2014