Climbing and musculoskeletal considerations

by Martin Krause

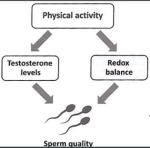

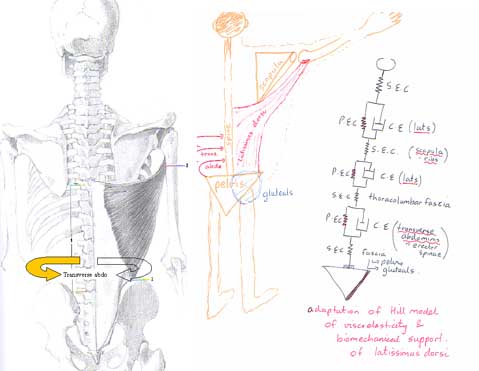

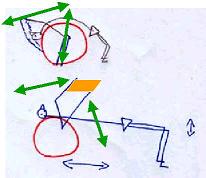

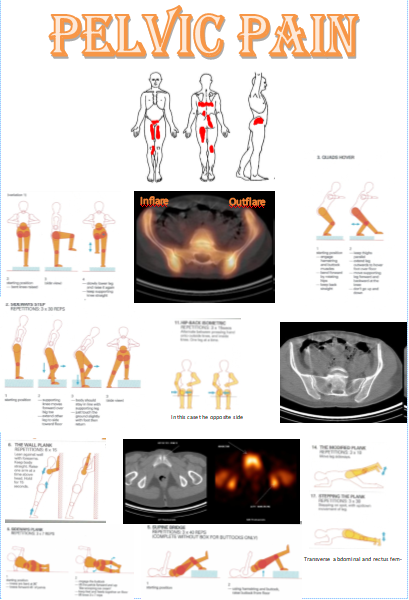

Good climbers use a combination of strength, endurance and flexibility. Power is developed by the arms through an upward throwing action of the arms, which instigates efficient eccentric muscle lengthening decelerating forces (rather than concentric - muscle shortening). Additionally, they are able to facilitate kinetic energy across the chain of movement from toes through the legs and pelvis into the trunk and torso.

Ideal posture

Ideal climbing involves

- extended arms to hang from

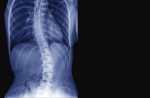

- thoracic extension, lateral flexion and rotation

- hip external rotation

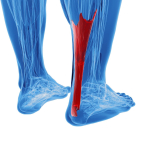

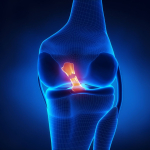

- knee flexion and slight heel rise to develop power through the legs

"An inch is a mile"

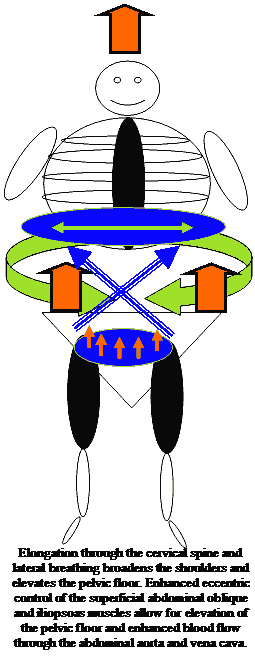

In climbing, 'an inch is a mile' refers to delicate foot and hand placement where body length through the elongation of the thorax with thoracic ring elevation. The shoulder blade needs to elevate and allow the thorax to hang from it.

Restrictions of thoracic rotation results in excessive contralateral gluteal contractions. Inadequate shoulder flexion due to limited thoracic ring extension can cause reduced contralateral gluteal activity

Gorillas on the Cliff

Climbers can develop a 'gorilla-like' posture due to over emphasis on

- grip

- arm flexion

- a '6 pack'

Since the abdominal muscles cross the lower 6 ribs, sufficient trunk core stability should not compromise the mobility (especially rotation) of the thorax.

Excessive development of the low thoracic - upper lumbar erector spinae can create

- reduced gluteal muscle strength,

- reduced diaphragmatic breathing,

- increased psoas major tightness and

- reduced core stability.

Postural problems associated with climbing could lead to musculoskeletal injury

- Climbers may develop a gorilla-like appearance due to the unique nature of the sport

- Gorilla-like appearance alters the centre of gravity of various limb and trunk segments

- this may lead to shoulder injuries, headaches, neck, arm and back pain

Stomach crunches or 'curls' may cause

- tightness of the rectus abdominis ("6 pack") and external obliques

at the expense of

- weakness of the transverse abdominis muscle

- increased thoracic kyphosis (rounded back)

- reduced diaphragmatic lateral expansion

which contributes to the gorilla posture resulting in

- altered thoracic biomechanics which affects active SLR and active PKB suggesting reduced lumbopelvic rhythm (gluteal : hamstring timing)

- reduced strength in the lumbo-pelvic-hip musculature

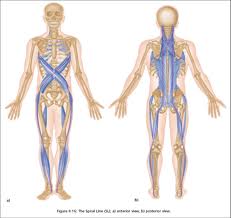

- reduced gliding of the myofascial trains extending from the superficial front line of the latissimus dorsi to the superficial back line of the thoracolumbar fascia and the gluteals

Arm elevation normally results in contralateral gluteal and transverse abdominal activity in the 'wall plank' position

Power = strength, speed and flexibility

Training should involve functional movement patterns, whereby some muscles are used as stabilisers whilst others are used as mobilisers. The deeper lying endurance muscles tend to be the stabilisers and are frequently found to cross only one joint or work in an area of limited movement. The mobilising, power muscles, tend to be the 'energy straps' crossing more than one joint and conferring kinetic energy to the movement system. A balance between mobility and stability needs to be attained.

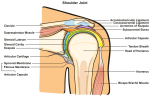

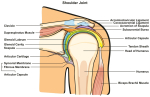

Excessive and prolonged reaching

- results in tight serratus anterior and pectoral (chest) muscles

- contributing to excessive strain on the blood vessels, nerves and joints of the shoulder - neck - arm complex

- creates excessive low thoracic erector spinae activity contributing to loss of costal expansion, as well as reduced diaphragmatic rhythm

- has been associated with impingement in the supraspinatus (superior rotator cuff) muscle leading to discomfort in the shoulder with loss of muscle power during activities above shoulder height

- Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular (collar bone joints) joints may become inflamed

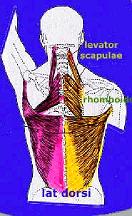

Overhead reaching can

- result in excessive strain on the back and shoulder blade muscles

- cause the rhomboids and levator scapulae to become long and weak

- facilitates the latissimus dorsi to become short and strong

- scalene muscle tightness, rib elevation and circulations compromise, similar to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

Training the shoulder blade muscles for prevention of shoulder-neck injuries

- requires a strong lower trapezius muscle for good posture

- needs a long and strong mid and upper trapezius muscle

- eccentric rhomboids

- coactivation of eccentric lats and concentric serratus anterior

Arm strength requires good gluteal muscle power

Training

- the trapezius muscles requires synergistic (complimentary) action by the

- latissimus dorsi

- erector spinae (back)

- oblique and transverse abdominal muscles (not the "6-pack"!!)

- the deltoid muscle requires synergistic action by the

- internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles

- contralateral gluteal activation

- lumbar erector spinae activity

- the serratus anterior needs synergy with the

- external obliques

- intercostals

- diaphragm

- should replicate the combination of muscle synergies in the most climbing functional way as possible.

Bridging exercises

with the Swiss Gym ball and elastic tubing allows

- functional activity which stretches the pectoral girdle and "6 pack"

- strengthening of the abdominal, spinal and shoulder blade muscles

- dynamic stability of the pelvis and hips allowing enhanced freedom of movement on the cliff face

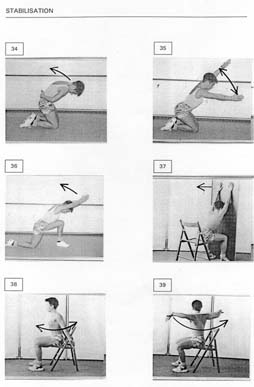

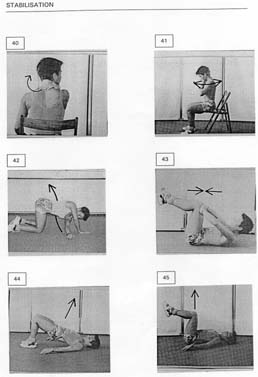

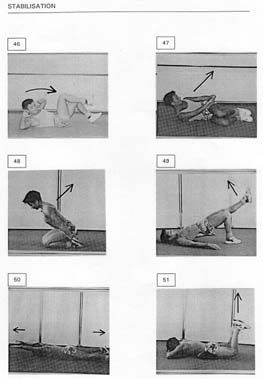

Functional exercises

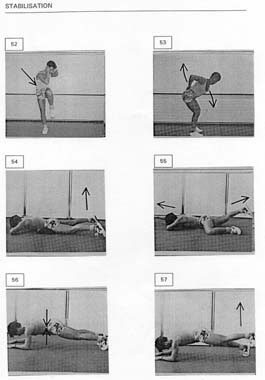

In climbing, ideally there are three points of contact, meaning that three points are either statically or dynamically stabilising whilst a limb is moving off the rock. The following describes a series of exercises for stability whilst moving various body parts

Modifications can be made into climbing patterns, such as semi squat rather than sitting

To reduce a "poked chin" the deep neck muscles need activation

seek guidance from your physiotherapist as the ultimate aim is to improve your power-weight ratio without inducing an injury

to other Swiss Ball and Hydrotherapy exercises

Last update : 10 October 2020