Biomechanical considerations of the multifidus muscle - is there a role for the modulation of inflammation?

by Martin Krause (2008)

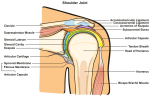

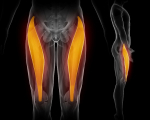

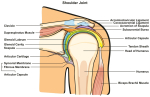

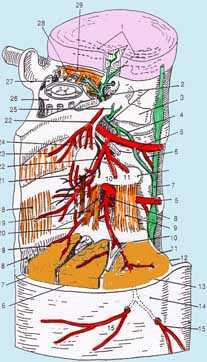

The multifidus muscle gained notoriety in the mid 1990's when researchers at Queensland University first demonstrated gross muscle atrophy using real-time ultrasound. Previously Lance Twomey and Nikolai Bogduk had remarked on the close anatomical nature of the multifidus to the capsule of the Zygapophysial joint and suggested that it may act similarly to the rotators cuff muscles of the shoulder. Moreover, they suggested that the angle of pull of these muscles and their relative shortness would make these muscles more likely to have a proprioceptive function working together with the oblique abdominals to sense rotation in the lumbar spine. Further support for this hypothesis came from additional evidence demonstrating that the multifidus had a higher concentration of annulospiral endings than other muscles.

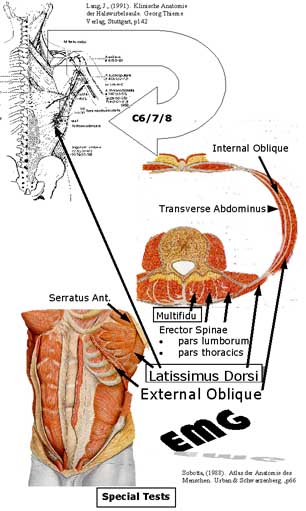

The function of the multifidus then became implicated with Transverse Abdominus function, as it's tendonous fascia placed tension on the fascia of the multifidus. Many EMG, US, MRI, CT and PET/functional MRI investigations followed. Indeed, the transverse abdominus is anatomically uniquely positioned to act as a stabilizer in the horizontal and transverse planes of motion for not only the L/S but also the SIJ's. Although it would seem obvious that synergistic muscle contractions would be superior to isolated ones, for about a decade, physiotherapists were statically stabilizing the lumbar spine with Transverse Abdominal contractions under dynamic US, whilst the external obliques and rectus abdominus were detrained. This seemed a curious notion as the multifidus was supposed to be a sensor for the oblique muscles. Furthermore, the natural postural swaying mechanisms in the saggital plane suggest rectus abdominus : erector spinae rhythm which in turn would control extensors torques on the lumbar spine as well as reduce excessive force closure. Additionally, the 4 point "happy cat" exercise results in rhythmical oscillations between the serratus anterior, external oblique and multifidus muscles whilst "the needle" encourages T/S rotational mobility whilst elongating and stabilizing the abdominal region using the external obliques.

The entire concept of detraining any muscle must be a fallacy as the better trained a muscle, the less likely it is to become overloaded, shortened and suffer both metabolic and mechanical failure. If a muscle can only lift 1kg and the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) require that muscle to lift 0.8kg then it will very quickly fatigue creating abnormal movement patterns, insecurity and a loss of form. If that muscle is trained up to lift 5kg, then the 0.8kg load becomes insignificant. Yet, even as recently as 2004, arguements raged as to the importance of low loading regimes for the treatment of low back pain (LBP). On the other hand, Stuart McGill, using investigations on highly trained weight lifters, was suggesting that maximal loading was best. Common sense dictates that the spectrum of loading is required for ADL.

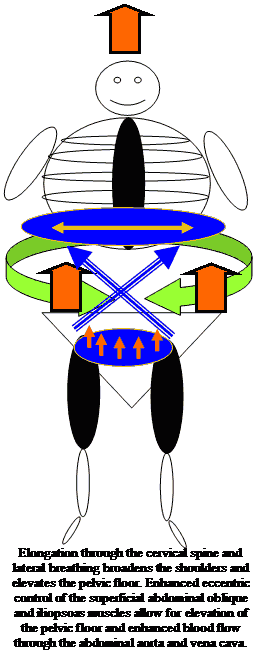

Beyond the multifidus and the transverse abdominus, it has become recently clear (2007) that the pelvic floor is immensely important in the stability of the lumbar spine. Here I would agree that these postural muscles require low loading since high loading will induce external oblique contractions which can place pressure on the bladder leading to incontinence. On the upper side of the barrel the other endurance muscle which requires long low lateral loading is the diaphragm. Previously, people were taught diaphragmatic breathing by stretching their stomach out. Yet, again this is counter-intuitive as it reduces the ability for transverse abdominus and internal oblique muscles to contract. Through lateral breathing, the lower 6 ribs can expand, placing an elongating contracting (eccentric) influence on the external obliques, whilst elongating the connections between the sympathetic ganglia. Also, by emphasising the slow 10 second breath (6 breaths per minute) it discourages hyperventilation which can lead to respiratory alkalosis and hence metabolic acidosis.

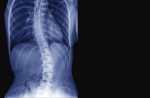

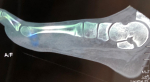

Yet, all things aside, the multifidus muscle clearly has a crucial role to play. Each day when I examine MRI's and CT's of the lumbar spine I see huge white areas of scar tissue or total blackness around the areas where the multifidus is supposed to be. This seems to be more prominent in the low lumbar spine, which in turn has significant bearing on the nutation of the sacrum as well as the propriocetive functions already described. The pelvic floor contraction on it's own will result in counter-nutation of the sacrum, which intuitively can be balanced by multifidus contractions on the sacrum.

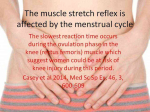

Beyond these biomechanical considerations, what role can a muscle such as multifidus have in the regulation of inflammation? In October 2005 I presented a paper in Rome on the importance of muscle mass on immune function. This was partially based on a paper I wrote in 2003 on Sarcopenia which is characterized by the reduction in muscle mass and may contribute to immunosenescence. Here, I argued that the muscles represent an important reservoir of protein required for immune function. (Rome presentation). In 1995, I argued for the importance of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) in the regulation of inflammation and repair in my treatise on mechanical traction. Late in 2007, 5 chapters (of 23) in DeLeo, Sorkin & Watins : Immune and Glial Regulation of Pain. IASP publication were devoted to the DRG and astrocyte-glial immune function in hyperalgesia and allodynia. Importantly, it was argued that retrograde signaling from the periphery and anterograde signaling from the DRG created a response by glial cells and astrocytes in the CNS. I had argued previously (1995) that such a mechanism should incorporate descending modulation by the sympathetic nervous system.

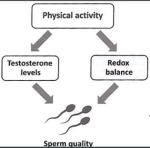

Hence, wouldn't it be interesting to generate a hypothesis, whereby exercising muscles innervated by the nerve affected by pathology would enhance immune-metabolic function not only of the muscle but may in turn help 'fine tune' the immune-metabolic function of the astrocytes and glia of the CNS? The electron transport chain (ETC) has been implicated in neuropathic pain. Similarly, the glutamine-glutamate energy systems have also been considered to be depleted in the cells of the DRG. The production of cytokines are also upregulated or downregulated depending upon the appropriatness of the response. Muscles can be trained to more successfully deal with oxygen free radicals (ROS). Since, muscle contractions involve glutamate, ETC and the balance of cytokine production, then it may be interesting to speculate that, the multifidus being the organ closest to the DRG may be optimally located for a CNS priming function???

Although, a lot of emphasis has been placed on motor control, perhaps the cognitive behavioral properties of motor control and their affect on the sympathetic nervous system are of primary importance when treating LBP and multifidus dysfunction????

Exercise and Growth Hormone

Bed rest can have deleterious effects on muscle function. Researchers have recently described a direct muscle afferent-pituitary axis whereby bio-assayable growth hormone (BGH) regulation is tightly coupled with muscle function rather than muscle fibre type. Unlike, exercise-induced increases in plasma immuno-assayable growth hormone (IGH), whose concentration peak occurs during or after longer duration aerobic or resistance exercise involving larger muscle mass, BGH is released after a brief series of isometric contraction (McCall et al 2001). The BGH response is absent , despite the maintenance of normal torque output and pre-exercise plasma BGH and IGH, when leg musculature is chronically unloaded, as after 2 days bed rest or space flight. They hypothesised that this was due to chronic alterations in proprioceptive inputs (McCall et al 2001). These responses normalised within approximately 8 days of ambulatory recovery. Furthermore, they suggested that BGH stimulates bone growth and that low threshold fibre activation through electrical stimulation, exercise and /or vibration may ameliorate the effects of chronic unloading (McCall et al 2001). Moreover, this is direct evidence for the existence of a muscle-pituitary functional pathway in the absence of inflammation. It also highlights the need not to underestimate the effects of bed rest when recommencing a training regime after a period of illness or trauma. Furthermore, it would appear that low threshold isometric contractions, as occur during the application of muscle energy techniques, may stimulate this growth hormone.

see :

Uploaded : 6 January 2008