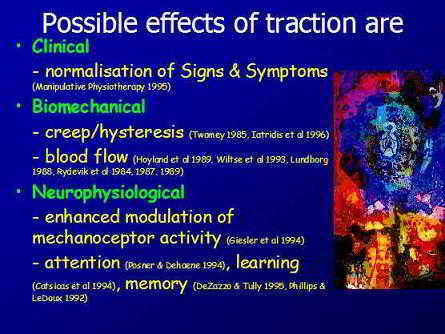

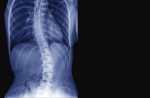

- neurophysiological, biomechanical (lumbar and thoracic), circulatory and clinical considerations and applications determining dose

Martin Krause (1995, 1999, 2004, 2006) M.Appl.Sc(Manip Physio), Grad.Dip.Hlth.Sc(Sport & Ex), Grad.Cert.Hlth.Sc.Edu

Table of Contents

Conditioned & Unconditioned Stimuli

Modulation of Mechanoceptor Acitivity

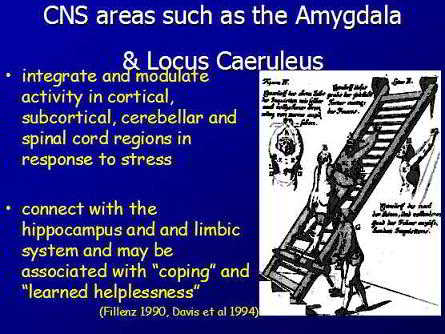

The Locus Coeruleus response to treatment stress

The role of feedback to descending modulation of pain and inflammation

Impaired Brain Processing w.r.t emotions and catastrophising

Theoretical Explanations - original paper on the effect of mechanical traction on neurogenic inflammation (1995)

Sensory Discriminative - Motivational Affective Components of Pain Processing

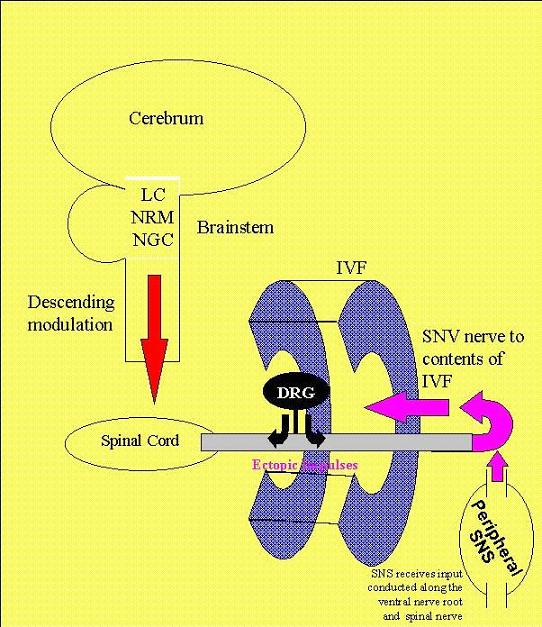

Ectopic Impulse Generation by the DRG

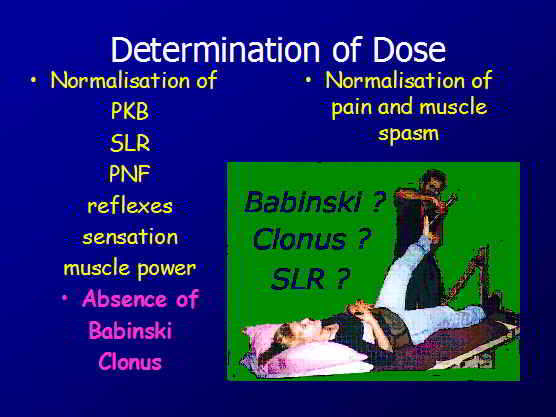

Normalisation of Signs and Symptoms using Traction

Clinical Implication of Neurophysiology on a 'Two Threshold' hypothesis

Validity of using the normalisation of signs and symptoms to establish the dose

Neurogenic inflammation and the cytokine immune response

Reduction of Venous Congestion

Sinuvertebral Nerve and Sympathetic Somatic coupling for healing

The brain's neural processing has been likened to a symphony orchestra playing in tune (Goldstein JA 2004). A type of resonance termed 'neural synchrony' has been related to arousal, attentional selection, and working memory. Grossberg (2000) highlights the relationship between matching top-down expectations with bottom-up data, a process which focuses attention on those features of the bottom-up input that are expected. The interaction of attention-learning and orienting-search subsystems and how they interact has been developed into adaptive resonance theory (ART). If there is appropriate stimulus generalisation then amplified representation can, in turn, attentionally block or inhibit the representations of irrelevant sensory events (Goldstein JA 2004). Therefore, radicular pain may represent a disturbance to CNS data processing and appropriate treatment may represent the attentional block which can help re-establish neural synchrony?

See Cochrane report (2006) for literature review.

Amazingly, a decade after the realisation that immediate normalisation of neurological signs and symptoms can occur if the appropriate dose of traction is applied, the research evidence still doesn't justify it's use.

Moreover, ever since the Ancient Greeks descibed traction for spinal nerve pain, 4000 years of dogma, continues to think that it's a mechanical effect on the low back, rather than a neurophysiological-mechanical effect on the thorax and peripheral sympathetic nervous system as well.

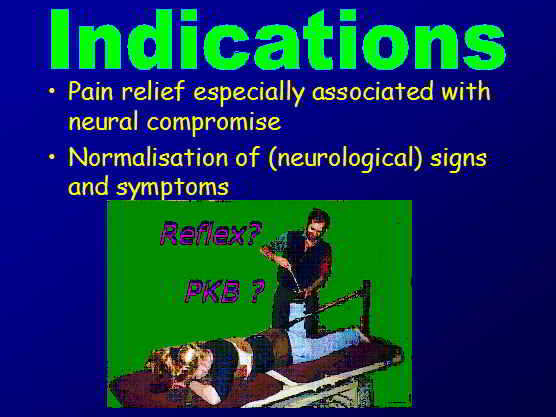

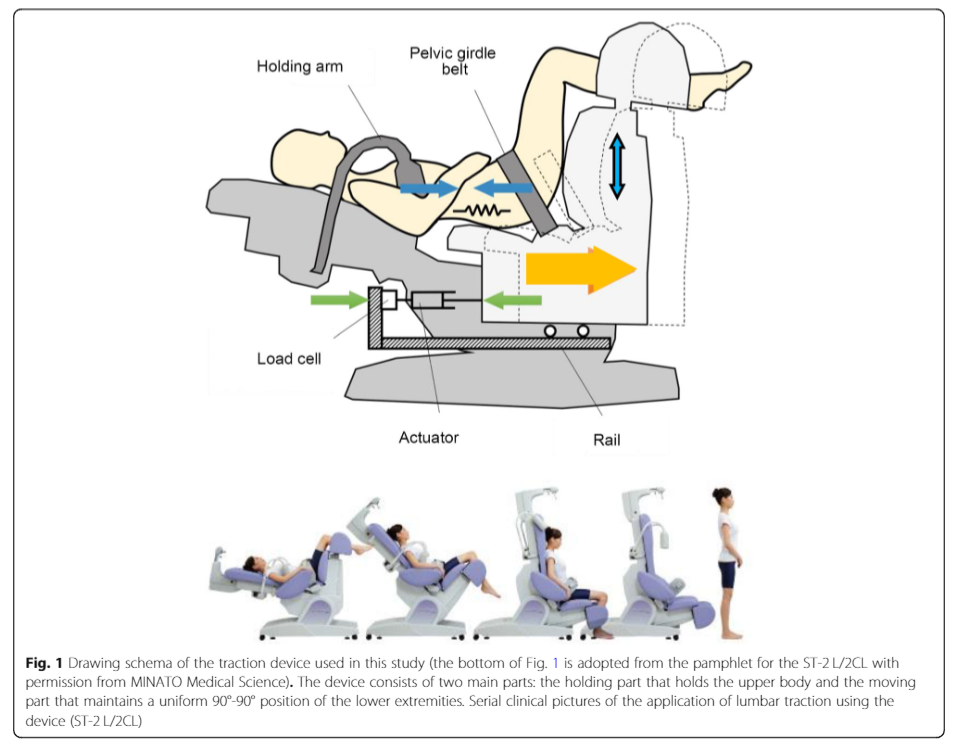

Hideki Tanabe et al (2021) Journal of Orthopaedic Science Volume 26, Issue 6, November, Pages 953-961

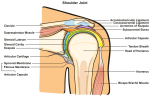

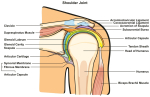

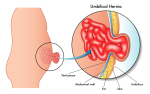

The misconception that traction affects the intervertebral disc (IVD) has come about because we are frequently treating pain that coexists with IVD pathology when a client presents with nerve pain and/or radiculopathy. However, attributing the pain symptoms to an MRI image has shown to be a fallacy in many instances, as 48-52% of the asymptomatic population will also have disc pathology on imaging with an MRI!!! Additionally, even if it is disc pathology that we are treating, the use of traction may be on the structures of the Intervertebral foramen (IVF) affected by the pathology. These include blood vessels, nerve root, dorsal root ganglion (DRG), spinal nerve, sinuvertebral nerve, vertebral ligaments (Ligamentum Flavum, long dorsal ligament), and the zygapophyseal joint capsule (Z-joint) itself. Moreover, swelling of the latter can create signs and symptoms classically associated with disc related nerve radiculopathy.

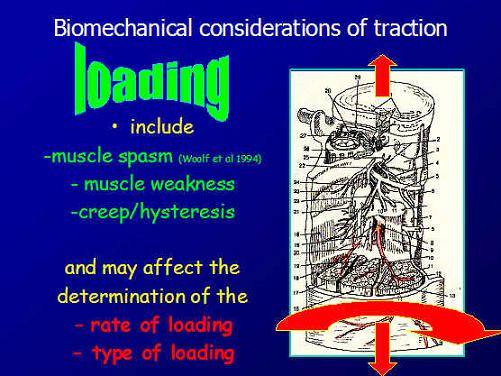

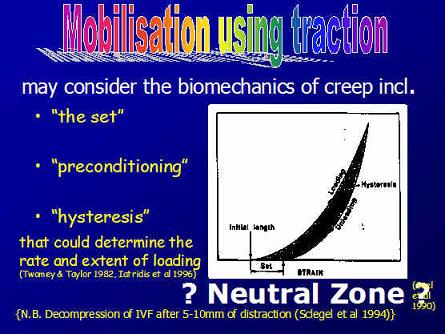

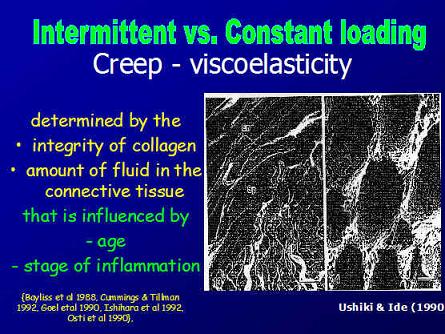

Such 'widening' could potentially just be movement within the 'neutral zone', where joint play occurs without passive structural soft tissue tension. It may also be that the reduction of muscle spasms by the 'unloading' of 'ectopic impulse generation' from pain or inflammation driven structures creates a greater 'neutral zone'. Breaking a vicious cycle of ectopic impulse generation and/or vascular engorgement may be the mechanism underlying the efficacy of traction. Additionally, taking ectopic impulse genration away from the sinuvertebral nerve, as well as stumilating peripheral sympathetic nervous system (SNS) modulation of neurogenic inflammation is a plausible effect of traction, not only in the IVF, but also on the ganglions of the peripheral SNS of the thorax. These ganglion reside parallel to the spine on the front aspect of the back part of the ribs - between ribs and the lung fields. Presumably, anything which improves the mechanics of the ebbs and flow of breathing, improves peripheral SNS function.

Note that the sinuvertebral nerve is a peripheral nerve

Note the blood vessels of a peripheral nerve. Other vascular structures include Batson's venous plexus. Interestingly, the DRG attains it's nutrients centrally from cerebrospinal fluid and potentially, peripherally, from axoplasmic flow. The sinuvertebral nerve, having a somatic and sympathetic innervation presumably is also involved with establishing metabolic and neurogenic homeostasis.

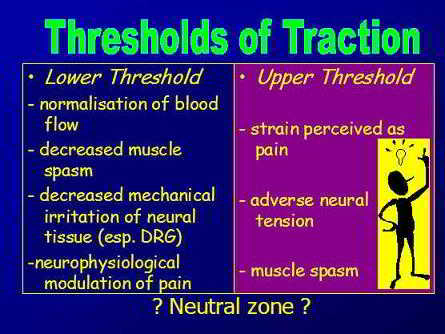

Thus, the hypothesis is that the neutral zone is 'unlocked' between two thresholds of loading. The lower threshold representing an ineffective force, whereas the upper threshold may actual represent loading of structures such as the IVD and longitudinal ligament. This would mean that the thresholds wouldn't vary a lot between the size and weight of the person, just by it's affect on the neurophysiology and metabolism of the pathology, the outcome of traction is based on the normalisation of the clinical neurological signs and symptoms, such as reflexes, skin sensation, muscle power and neural tension. Additionally, improvements of 'thoracic ring' biomechanics can also be simultaneously assessed through palpation from joint mobilisation.

Hideki Tanabe et al (2021) Journal of Orthopaedic Science Volume 26, Issue 6, November, Pages 953-961

Through the normalisation of muscle spasm, the amount of 'force closure' around the spine should reduce. Consequently, such a reduction in muscle tension should reduce compressive forces on the intervertebral discs and blood vessels of the intervertebral foramen as well as the spinal canal (Batson's venous plexus). Presumably, this alters the feedback (afferent) and feed-forward (efferent) mechanisms of the sympathetic nervous system.

Normalisation of pressure around the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) should reduce the propagation of ectopic impulses to the spinal cord and and sinuvertebral nerve, which should, moreover, improve the afferent-efferent interaction in the periphery. The latter would improve the modulation of blood flow (arterial and venous) as well as the modulation of neurogenic inflammation. It should be remembered that the sinuvertebral nerve is a 'mixed' peripheral nerve responsible for these effects within the intervertebral foramen and spinal canal.

Sympathetic-sensory coupling after L5 spinal nerve lesion in the rat and its relation to changes in dorsal root ganglion blood flow

H. -J. Haebler, S. Eschenfelder, X. -G. Liu and W. Jaenig

Abstract

Transection of the L5 spinal nerve in rats results in allodynia- and hyperalgesia-like behaviour to mechanical stimulation which are thought to be mediated by ectopic activity arising in lesioned afferent neurons mainly in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). It has been suggested that the neuropathic pain behaviour is dependent on the sympathetic nervous system. In rats 3–56 days after L5 spinal nerve lesion, we tested responses of axotomized afferent fibres recorded in the dorsal root of the lesioned segment to norepinephrine (NE, 0.5 ![]() g/kg) injected intravenously and to selective electrical stimulation of the lumbar sympathetic trunk (LST). In some experiments we measured blood flow in the DRG by laser Doppler flowmetry. The majority of lesioned afferent fibres with spontaneous activity responded to neither LST stimulation (82.4%) nor NE (71.4%). In those which did react to LST stimulation, responses occurred only at high stimulation frequencies (likely to be above the physiological range), and they could be mimicked by non-adrenergic vasoconstrictor drugs (angiotensin II, vasopressin). Excitatory responses to LST stimulation were closely correlated with the stimulation-induced phasic vasoconstrictions in the DRG. We therefore hypothesized that the activation of lesioned afferents might be brought about indirectly by an impaired blood supply to the DRG. To test this hypothesis we induced a strong and sustained baseline vasoconstriction in the DRG by blocking endothelial nitric oxide synthesis with N G -nitro- NAME. These results show that sympathetic-sensory coupling occurs only in a minority of axotomized afferents after L5 spinal nerve injury. Like previous studies, they cast doubt on the notion that the L5 spinal nerve lesion is a good model for sympathetically maintained pain. Since responses of lesioned afferent neurons to LST stimulation and NE could be provoked with high reliability after inducing vasoconstriction in the DRG, and since they mirrored stimulation-induced vasoconstrictions in the DRG, it appears that in this model the association of sympathetic activity with afferent discharge occurs mainly when perfusion of the DRG is impaired.

g/kg) injected intravenously and to selective electrical stimulation of the lumbar sympathetic trunk (LST). In some experiments we measured blood flow in the DRG by laser Doppler flowmetry. The majority of lesioned afferent fibres with spontaneous activity responded to neither LST stimulation (82.4%) nor NE (71.4%). In those which did react to LST stimulation, responses occurred only at high stimulation frequencies (likely to be above the physiological range), and they could be mimicked by non-adrenergic vasoconstrictor drugs (angiotensin II, vasopressin). Excitatory responses to LST stimulation were closely correlated with the stimulation-induced phasic vasoconstrictions in the DRG. We therefore hypothesized that the activation of lesioned afferents might be brought about indirectly by an impaired blood supply to the DRG. To test this hypothesis we induced a strong and sustained baseline vasoconstriction in the DRG by blocking endothelial nitric oxide synthesis with N G -nitro- NAME. These results show that sympathetic-sensory coupling occurs only in a minority of axotomized afferents after L5 spinal nerve injury. Like previous studies, they cast doubt on the notion that the L5 spinal nerve lesion is a good model for sympathetically maintained pain. Since responses of lesioned afferent neurons to LST stimulation and NE could be provoked with high reliability after inducing vasoconstriction in the DRG, and since they mirrored stimulation-induced vasoconstrictions in the DRG, it appears that in this model the association of sympathetic activity with afferent discharge occurs mainly when perfusion of the DRG is impaired.

Author Keywords: Neuropathic pain; L5 spinal nerve injury; Sympathetically maintained pain; Dorsal root ganglion; Neurogenic vasoconstriction; Sympathetic nervous system

If one considers the sinuvertebral nerve to be a peripheral nerve then induction of inflammation around the DRG can in turn create changes within the DRG which leads to hyperalgesia. Clearly a vicious cycle may ensue.

The sinuvertebral nerve consisting of the somatic and peripheral sympathetic nerves will be influenced by any mechanical input on the thorax. Low back mechanical traction , does traction the entire thoracic spine.

Induction of high mobility group box-1 in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) contributes to pain hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury

Masayuki Shibasaki et al (2010) Pain, Volume 149, Issue 3, 514-521

Abstract

Pro-inflammatory cytokine high mobility group box-1 (HMGB-1) is involved in inflammation in the central nervous system, but less is known about its biological effects in the peripheral nervous system. In the present study, the role of HMGB-1 in the primary afferent nerve was investigated in the context of the pathophysiology of peripheral nerve injury-induced pain hypersensitivity. Real-time PCR confirmed an increase in HMGB-1 mRNA expression in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and spinal nerve at 1day after spinal nerve ligation (SNL). Induction of HMGB-1 mRNA was observed in both injured L5 and uninjured L4. Immunohistochemistry for HMGB-1 revealed that SNL-induced HMGB-1 expression in the primary afferent neurons and satellite glial cells (SGCs) in the DRG, and in Schwann cells in the spinal nerve. Up-regulation of HMGB-1 was associated with translocation of its signal from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Injection of HMGB-1 into the sciatic nerve produces transient behavioural hyperalgesia. Neutralizing antibody against HMGB-1 successfully alleviated the mechanical allodynia observed after SNL treatment. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), one of the major receptors for HMGB-1, was expressed in the primary afferent neurons and SGCs in the DRG, as well as in Schwann cells in the spinal nerve. These results indicate that HMGB-1 is synthesized and secreted into the DRG and spinal nerve, and contributes to the development of neuropathic pain after nerve injury. Blocking HMGB-1/RAGE signalling might thus be a promising therapeutic strategy for the management of neuropathic pain.

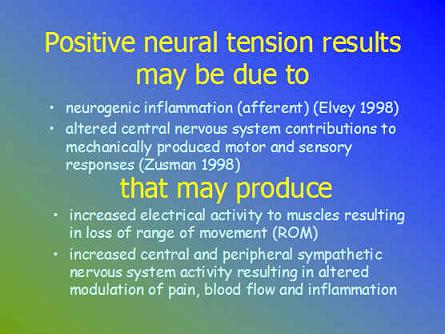

Adverse Neural Tension includes that around the sciatic nerve as well as the Dura Mater of the spinal canal and the peripheral sympathetic ganglia chain. Note that the sinuvertebral nerve (SNV) is composed of fibres from both the somatic and peripheral sympathetic nervous system.

It should be noted that in many instances of radiculopathy, the range of motion (ROM) of Straight Leg Raise (SLR) is reduced due to neurogenic muscle spasms. However, there are instances where the pressure on the nerve is so great that the actual protective mechanism is inhibited. The SLR will feel 'empty' devoid of normal muscle tone, let alone muscle spasms. This is a very dangerous scenario. Therefore, it is important not to dose mechanical traction solely on SLR, but also on other neurological S+S such as tendon reflexes, muscle power and skin sensation.

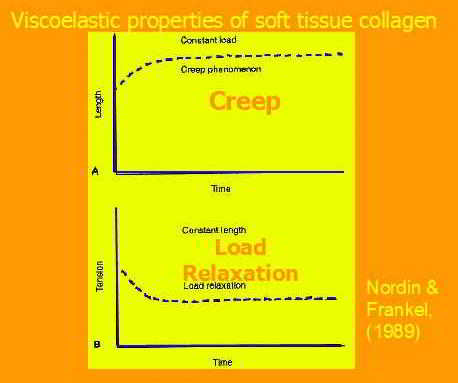

This 'neutral zone' is different to one described previously. In the first instance the neutral zone is the movement which occurs before collagen fibres are stretched, the latter, represents the 'crimp' in the collagen fibres, whereby, the 'curly' appearance of collagen soft tissue is stretch out until collagen resistance commences. This process requires the movement of 'fluid' within the realm of the collagen matrix.

Higher centre responses to and perception of mechanical traction

Conditioned stimulus and unconditioned stimulus inputs converge on individual cells in the lateral amygdala, which is the principal output nucleus of fear system projects to areas of the hypothalamus and brainstem that control behavioural, endocrine, and autonomic conditional responses associated with fear learning (Goldstein JA 2004). In neurosomatic disorders, an accentuation of the attentional weighting is given to elements of a stimulus that, in actuality, have a very tenuous relationship to the state of activation of the long-term memory store. Unlike the individual with a normally functioning neural network for associated learning, the activated memory store to which the stimulus is associated does not rapidly decay but continues to be highly weighted, even if this weighting is outside the individual's attention (Newport DJ, Nemeroff CV 2000; in Goldstein JA 2004).

Attentional resources are allocated in favour of unexpected salient events. The term 'switching' is used to denote reallocation processes, and 'salient' is used to refer to stimuli with special biological significance. Dopaminergic output is involved in 'behavioural orienting', the allocation of attention to a particular stimulus. This response normally extinguishes rapidly. Unexpected rewards or punishments lead to the acquisition of new conditioned responses. Dopaminergic activity is suppressed when expected rewards fail to materialize. Basal ganglia have evolved to resolve conflicts of multiple subsystems competing for access to limited motor or cognitive resources ( see orienteering section of website for more details ). The frontal eye fields brings visual stimuli into the most active perceptual area of the retina, so it's potential reward significance can be determined. The computations of the possible reward occur before the behavioural switch occurs, and a signal is often lost before the identity of the stimulus is fully known (Goldstein JA 2004).

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) and noradrenergic systems are both important for attentional regulation. Lesions of the PFC impair the ability to sustain attention to relevant information and to inhibit processing of irrelevant stimuli. Neurones in the locus coereleus (LC) fire in relation to the attentional state, and the PFC is one of the few high-order inputs to the LC and is an important regulator of it's activity. Noradrenaline is known to enhance signal-to-noise ratio in sensory cortices. With insufficient noradrenergic stimulation, small signals may be obscured (targets) while potent stimuli may be processed (distractors). If noradrenaline is hyper-secreted, it would take the PFC 'off line'. The PFC may be responsible for exploratory responses in a fear-inducing environment (Goldstein JA 2004). Therefore, higher centres are most probably involved in assessing the visual input during the assessment of signs and symptoms.

Placebo versus Nocebo effect

Mechanism of placebo analgesia : rACC recruitment of a subcortical antinociceptive network

Bingel U et al (2006) Pain Journal, 120. 1-2, 8-15

Abstract

Placebo analgesia is one of the most striking examples of the cognitive modulation of pain perception and the underlying mechanisms are finally beginning to be understood. According to pharmacological studies, the endogenous opioid system is essential for placebo analgesia. Recent functional imaging data provides evidence that the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) represents a crucial cortical area for this type of endogenous pain control. We therefore hypothesized that placebo analgesia recruits other brain areas outside the rACC and that interactions of the rACC with these brain areas mediate opioid-dependent endogenous antinociception as part of a top–down mechanism. Nineteen healthy subjects received and rated painful laser stimuli to the dorsum of both hands, one of them treated with a fake analgesic cream (placebo). Painful stimulation was preceded by an auditory cue, indicating the side of the next laser stimulation. BOLD-responses to the painful laser-stimulation during the placebo and no-placebo condition were assessed using event-related fMRI. After having confirmed placebo related activity in the rACC, a connectivity analysis identified placebo dependent contributions of rACC activity with bilateral amygdalae and the periaqueductal grey (PAG). This finding supports the view that placebo analgesia depends on the enhanced functional connectivity of the rACC with subcortical brain structures that are crucial for conditioned learning and descending inhibition of nociception.

Keywords: Pain; Placebo; rACC; fMRI; PAG; Amygdala; PPI

>Dissection of perceptual, motor and autonomic components of brain activity evoked by noxious stimulation

M. Pichéacef, M. Arsenaultcde, P. Rainville (2010) Pain, Volume 149, Issue 3, Pages 453-462

Abstract

In the past two decades, functional brain imaging has considerably advanced our knowledge of cerebral pain processing. However, many important links are still missing in our understanding of brain activity in relation to the regulation of pain-related physiological responses. This fMRI study investigates the cerebral correlates of pain (rating), motor responses (RIII-reflex) and autonomic activity (skin conductance response; SCR) evoked by noxious electrical stimulation. Stimulus intensity was adjusted individually based on the RIII threshold to control for differences in peripheral processes and baseline spinal activation. Covariance analyses were used to reveal individual differences in brain activity uniquely associated with individual differences in pain, RIII and SCR. Shock-evoked activity in cingulate, medial orbitofrontal and parahippocampal regions predicted pain sensitivity. Moreover, lateral orbitofrontal and cingulate areas showed strong positive associations with individual differences in motor reactivity but negative associations with autonomic reactivity. Notably, individual differences in OFC activation was almost fully accounted by the combination of individual measures of autonomic and motor reactivity (R2=0.93). Additionally, trial-to-trial fluctuations of RIII-reflex and SCR (within-subjects) were proportional to shock-evoked responses in subgenual cingulate cortex (RIII), anterior insula (SCR) and midcingulate cortex (SCR and RIII). Together, these results confirm that individual differences in perceptual, motor, and autonomic components of pain reflect robust individual differences in brain activity. Furthermore, the brain correlates of trial-to-trial fluctuations in pain responses provide additional evidence for a partial segregation of sub-systems involved more specifically in the ongoing monitoring, and possibly the regulation, of pain-related motor and autonomic responses.

Interested readers should look at pain and the brain elsewhere on this site

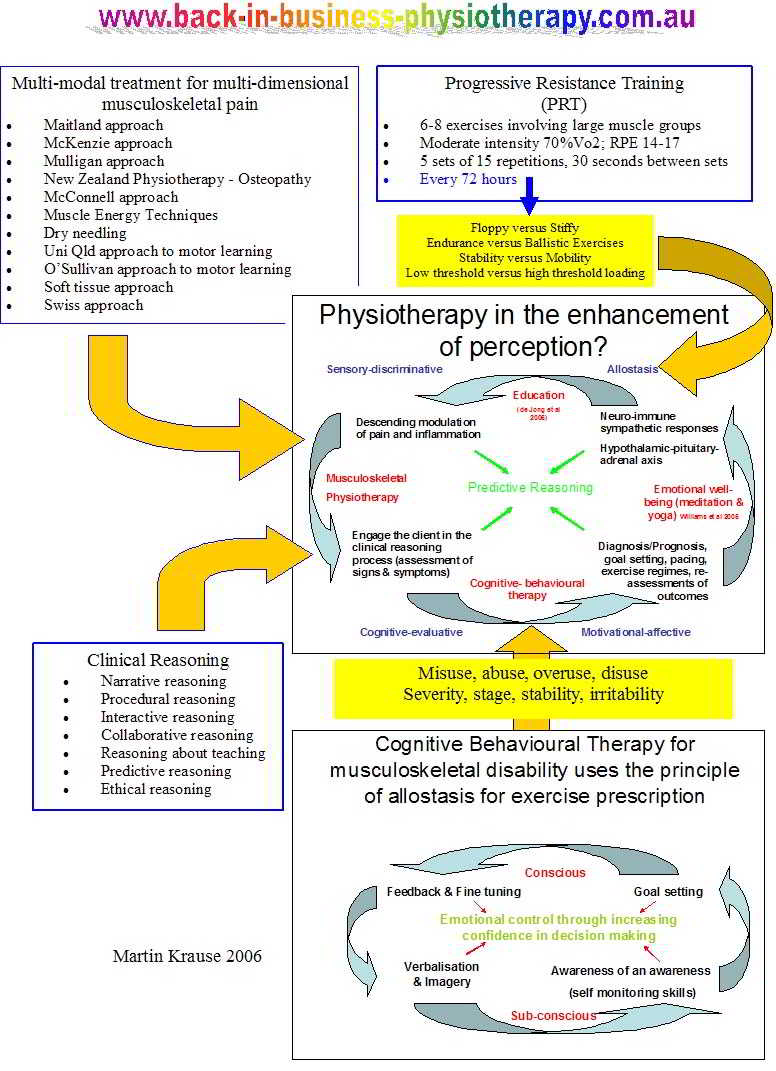

The Neuromatrix

According to Melzack (1999) the sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational and evaluative-cognitive dimensions of pain experience are determined by the multiple inputs that act on the neuromatrix programmes. These include sensory inputs, visual inputs which influence the cognitive interpretation of the situation, phasic and tonic cognitive inputs from other areas of the brain, intrinsic neural inhibitory modulation, activity of the body's stress-regulation systems including cytokines, as well as endocrine, autonomic, immune and opioid systems. Therefore, the role of mechanical traction within a multi-modal approach would be a useful clinical research paradigm.

Multimodal approach to treatment of musculoskeletal conditions.

Chronic stress may have a direct influence on pain.

Increased basel mechanical sensitivity but decreased perceptual wind-up in a human model of relative hypocorticolism

Linn K. Kuehla, Gilles P. Michaux (2010) Pain, Volume 149, Issue 3, Pages 539-546

Abstract

Clinical data have accumulated showing that relative hypocortisolism, which may be regarded as a neuroendocrinological correlate of chronic stress, may be a characteristic of some functional pain syndromes. However, it has not been clarified yet whether deregulations of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis may directly alter pain perception and thus be causally involved in the pathophysiology of these disorders. To test this hypothesis, we performed a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial in N=20 healthy drug-free volunteers (median age 24yrs) and analyzed the effects of metyrapone-induced hypocortisolism on quantitatively assessed basal mechanical pain sensitivity (1.5–13m/s impact stimuli), perceptual wind-up (9m/s impact stimuli at 1Hz) and temporal summation of pain elicited by inter-digital web pinching (IWP; 10N pressure stimuli for 2min). Experimentally induced hypocortisolism significantly decreased pain detection thresholds and augmented temporal summation of IWP-induced pain (p<.05). The latter effect was dependent on the relative reduction in cortisol levels, and seemed to rely on a potentiated sensitization and not merely on the observed changes in basal pain sensitivity. Perceptual wind-up by contrast was reduced when cortisol synthesis was blocked (p<.05). This result is reminiscent of findings from animal studies showing a reversal of NMDA receptor activation by glucocorticoid receptor antagonists in neuropathic pain models. Our results speak in favour of a potential causal role of HPA axis alterations in pain chronicity.

Altered proprioception and perception - dura mater and adverse neural tension

It is plausible that traction provides a unique stimulus to the spinal canals dura mater. Normally, when we bend forward, the posterior aspect of the dura mater 'unfolds', similarly when we bend back, it's the anterior aspect and sideways the contralateral side. However, mechanical traction may give the brain, the perception of simultaneous movement in all directions, thereby relaxing (antagonist) muscles to allow movement to occur. Additionally, this longitudinal stimulus may stimulate the peripheral sympathetic ganglia, producing an autonomic response. Regardless, clinically, the range of movement in side bending and rotation of the thorax frequently improve. Additionally, side bending of the cervical spine also frequently occurs. So much so, that i am frequently using lumbar spine mechanical traction whilst simultaneously mobilising the cervical spine and upper thoracic rings.

Re-setting of muscles

The re-setting of muscles after mechanical traction is designed to re-establish the normal 'muscle slings' which support the spine. Such 'sling stabilisation' is in line with Andre Vleeming's work as well as that of myofascial trains practitioners and 'tensegrity' biomechanists. Examples of some of these exercises can be found at the end of the rock climbing page, elsewhere on this site.

The 2 threshold hypothesis of dose suggests that a therapeutic dose (normalisation of signs and symptoms) for lumbar spine traction occurs at a very low threshold of around 8-10kg and another threshold occurs with a deterioration of signs and symptoms at 18-20kg and even as low as 12kg. These values vary to some extent depending on the stage, stability, irritability and stability of the disorder.

Hence, it appears to be important to engage the client in the clinical reasoning process. In so doing, they are not passive recipients of treatment. Rather, their cognitive processes are involved with the aims and objectives of treatment as well as expected outcome. Additionally, their motor systems are involved not only in the re-evaluation of signs, but also in the re-establish of correct muscle co-ordination and stability post traction. Importantly, general consensus suggests that multi-modal treatment approaches within the clinical reasoning frame of reference is more efficacious than using one modality alone. Hence, treatment with mechanical traction should be integrated with other techniques such as joint mobilisations of the hip & thoracic spine, muscle energy techniques, soft tissue massage, trigger point massage, fascial release, dry needling, taping, and exercise regimes appropriate for the stage, stability, severity, & irritability of the disorder, whilst respecting biomechanical principles of inverse dynamics.

It should be noted however, that patients who have high scores on the Catastrophizing Scale of the CSQ (Coping Strategies Questionnaire : Rosentiel & Keefe 1983), who endorse passive coping strategies on the PMI (Pain Management Inventory : Brown et al 1989), who demonstrate low self efficacy regarding their ability to manage their pain on the PSEQ (Pain self efficacy questionnaire : Lorig et al 1989), who describe themselves as disabled by their pain on the SOPA (Survey of pain attitudes : Jensen et al 1987), and who report negative thoughts about their pain on the INTRP (Inventory of negative thoughts in response to pain : Gil et al 1990) are at greatest risk for poor treatment outcome (Jamison 2004).

For more information on Musculoskeletal Low Back Pain and treatments LBP Treatment Progress.

Further evidence regarding psychological aspects of pain and impaired brain processing come from the following investigations :

Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task

A. Vania Apkarian et al (2004) Pain, 108, 129-136

Abstract

Chronic pain can result in anxiety, depression and reduced quality of life. However, its effects on cognitive abilities have remained unclear although many studies attempted to psychologically profile chronic pain. We hypothesized that performance on an emotional decision-making task may be impaired in chronic pain since human brain imaging studies show that brain regions critical for this ability are also involved in chronic pain. Chronic back pain (CBP) patients, chronic complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) patients, and normal volunteers (matched for age, sex, and education) were studied on the Iowa Gambling Task, a card game developed to study emotional decision-making. Outcomes on the gambling task were contrasted to performance on other cognitive tasks. The net number of choices made from advantageous decks after subtracting choices made from disadvantageous decks on average was 22.6 in normal subjects ( n =26), 13.4 in CBP patients ( n =26), and -9.5 in CRPS patients ( n =12), indicating poor performance in the patient groups as compared to the normal controls ( P <0.004). Only pain intensity assessed during the gambling task was correlated with task outcome and only in CBP patients ( r =-0.75, P <0.003). Other cognitive abilities, such as attention, short-term memory, and general intelligence tested normal in the chronic pain patients. Our evidence indicates that chronic pain is associated with a specific cognitive deficit, which may impact everyday behavior especially in risky, emotionally laden, situations.

Author Keywords: Chronic pain; Depression; Decision-making task

Dimensions of catastrophic thinking associated with pain experience and disability in patients with neuropathic pain conditions.

Michael J.L. Sullivan et al (2005) Pain 113, 310-315

Abstract

The objective of the present study was to examine the relative contributions of different dimensions of catastrophic thinking (i.e. rumination, magnification, helplessness) to the pain experience and disability associated with neuropathic pain. Eighty patients with diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, post-surgical or post-traumatic neuropathic pain who had volunteered for participation in a clinical trial formed the basis of the present analyses. Spontaneous pain was assessed with the sensory and affective subscales of the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pinprick hyperalgesia and dynamic tactile allodynia were used as measures of evoked pain. Consistent with previous research, individuals who scored higher on a measure of catastrophic thinking (Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PCS) also rated their pain as more intense, and rated themselves to be more disabled due to their pain. Follow up analyses revealed that the PCS was significantly correlated with the affective subscale of the MPQ but not with the sensory subscale. The helplessness subscale of the PCS was the only dimension of catastrophizing to contribute significant unique variance to the prediction of pain. The PCS was not significantly correlated with measures of evoked pain. Catastrophizing predicted pain-related disability over and above the variance accounted for by pain severity. The findings are discussed in terms of mechanisms linking catastrophic thinking to pain experience. Treatment implications are addressed.

Keywords: Catastrophizing; Helplessness; Neuropathic pain; Affective pain

Self-management of chronic pain: a population-based study

Fiona M. Blyth , et al (2005) Pain 113, 285-292

Abstract

While effective self-management of chronic pain is important, clinic-based studies exclude the more typical pattern of self-management that occurs in the community, often without reference to health professionals. We examined specific hypotheses about the use of self-management strategies in a population-based study of chronic pain subjects. Data came from an Australian population-based random digit dialling computer-assisted telephone survey and included 474 adults aged 18 or over with chronic pain (response rate 73.4%). Passive strategies were more often reported than active ones: passive strategies such as taking medication (47%), resting (31.5%), and using hot/cold packs (23.4%) were most commonly reported, while the most commonly reported active strategy was exercising (25.8%). Only 33.5% of those who used active behavioural and/or cognitive strategies used them exclusively, while 67.7% of those who used passive behavioural and/or conventional medical strategies did so exclusively. Self-management strategies were associated with both pain-related disability and use of health services in multiple logistic regression models. Using passive strategies increased the likelihood of having high levels of pain-related disability (adjusted OR 2.59) and more pain-related health care visits (adjusted OR 2.9); using active strategies substantially reduced the likelihood of having high levels of pain-related disability (adjusted OR 0.2). In conclusion, we have shown in a population-based study that clinical findings regarding self-management strategies apply to the broader population and advocate that more attention be given to community-based strategies for improving awareness and uptake of active self-management strategies for chronic pain.

Keywords: Self-care; Chronic pain; Epidemiology

Also see the following investigations into the role of neuro-immune substances in pain modulation

Tumor necrosis factor a and interleukin-1ß stimulate the expression of cyclooxygenase II but do not alter prostaglandin E 2 receptor mRNA levels in cultured dorsal root ganglia cells

Jill C. Fehrenbacher, et al (2004) Link to article at on-line Pain journal at Elsevier.com

Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor a (TNFa) and interleukin 1ß (IL-1ß) are pro-inflammatory cytokines capable of altering the sensitivity of sensory neurons. Because sensitization elicited by IL-1ß and TNFa is blocked by inhibition of the inducible enzyme, cyclooxygenase-II (COX-2), we examined whether these cytokines could increase COX-2 expression in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cultures. Treatment of cell cultures with either IL-1ß or TNFa increases immunoreactive COX-2, as measured by immunoblotting, in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. A 24-h pretreatment with 10 ng/ml IL-1ß or 50 ng/ml TNFa augmented COX-2 expression 50- and 8-fold over basal levels, respectively. Immunohistochemistry established the presence of COX-2-like immunoreactivity in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells in culture. The addition of IL-1 receptor antagonist blocked the induction of COX-2 expression by IL-1ß, but did not alter TNFa-stimulated increases in COX-2, indicating that the mechanism of TNFa is not limited to increasing the expression of IL-1ß. The basal and TNFa-induced expression of COX-2 was not dependent on the presence of NGF in the growth media. IL-1ß and TNFa treatment for 24 h enhanced prostaglandin E 2 (PGE 2 ) production 2–4-fold, which was blocked by pretreatment with the COX-2 inhibitor, NS-398. Exposing cultures to PGE 2 , IL-1ß, or TNFa for 24 h did not alter PGE 2 receptor (EP) mRNA levels. These results indicate that TNFa and IL-1ß induce the functional expression of COX-2 but not EP receptors in DRG cells in culture and suggest that cytokine-induced sensitization of sensory neurons is secondary to prostaglandin production and not alterations in EP receptors.

Excitatory and modulatory effects of inflammatory cytokines and neurotrophins on mechanosensitive group IV muscle afferents in the rat

Ulrich Hoheisel et al (2005) Link to Pain Journal

Abstract

In inflamed tissue – including skeletal muscle – the concentrations of cytokines and neurotrophins are known to increase. However, nothing is known about a possible contribution of these agents to muscle pain and hyperalgesia. The present study investigated acute effects of cytokines and neurotrophins on response properties of slowly conducting muscle afferents. In anaesthetised rats, the impulse activity of single mechanosensitive group IV fibres innervating the gastrocnemius–soleus muscle was recorded and tumour necrosis factor-a (TNF-a), interleukin-6 (IL-6), nerve growth factor (NGF), or brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were injected into the muscle. Changes in the mechanosensibility of the endings following administration of the agents were tested with repeated pressure stimuli of defined forces. A low mechanical threshold in the innocuous range was found in 44.4% of the units tested, 55.6% required strong, potentially tissue-damaging pressure stimuli for activation. NGF excited only units that had a high mechanical threshold, while IL-6 was a stimulant for low-threshold mechanosensitive units only. TNF-a and BDNF did not excite group IV units but had a desensitising action: after TNF-a or BDNF, the response magnitudes to pressure stimuli decreased significantly. The data indicate that cytokines and neurotrophins influence the impulse activity and mechanosensitivity of group IV muscle afferent units. These effects could be of functional significance when the agents are released from muscle cells under pathophysiological circumstances.

Keywords: Group IV afferent units; Skeletal muscle; Cytokines; Neurotrophins; Nociception

Spinal nerve lesion-induced mechanoallodynia and adrenergic sprouting in sensory ganglia are attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice

Matt S. Ramer et al (1998) link to Pain Journal

Abstract

Tight ligation and transection of the L5 spinal nerve (SNL) gives rise to pain which is dependent upon activity in the sympathetic nervous system. It also results in novel adrenergic sympathetic innervation of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) with the formation of pericellular axonal basket structures around some DRG neurons. Since the sympathetic sprouting and basket formation may represent an anatomical basis for pain-generating interactions between the sympathetic efferent neurons and sensory afferent neurons, it is of great interest to determine possible chemical mediators of this phenomenon. Previous findings have shown that IL-6 can contribute to sympathetically-independent pain, and can give rise to thermal hyperalgesia when injected intrathecally. We have now investigated a possible contributory role of the pleiotropic cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) in sympathetically-mediated pain: we gave IL-6 knockout mice and mice of the parent strain c57B6/129 a SNL, assessed their resulting pain behaviour for 10 days post-surgery, and used tyrosine-hydroxylase immunohistochemistry to compare sympathetic sprouting in the DRG at the end of the testing period. We found that thermal allodynia (as assessed by measuring the latency to withdrawal from radiant heat) did not differ significantly between strains. On the other hand, in the IL-6 mice, mechanoallodynia (as assessed with von Frey filaments) was markedly delayed. Sympathetic invasion of the fibre tract and cell layer of the DRG, and the formation of pericellular axonal baskets were all significantly reduced in the IL-6 knockout mice compared to the control strain. These results imply a facilitatory role for IL-6 in pain and sympathetic sprouting induced by nerve injury, and add to the growing list of roles for IL-6 in neuropathological events.

Author Keywords: Sympathetic sprouting; Allodynia; Hyperalgesia; DRG; Cytokines; Mice

Index Terms: spinal nerve; nerve injury; allodynia; hyperalgesia; interleukin 6

Other useful links on the site

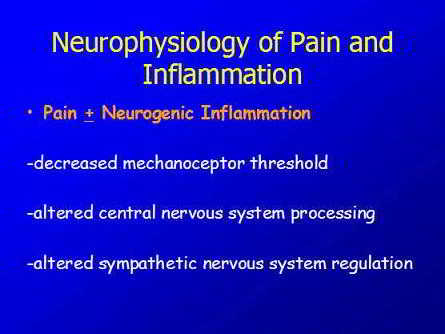

Neurophysiology of Pain and Inflammation

Clinical example using mechanical traction

Presentation on Stress, Exercise and the Immune System

Mechanical traction neurophysiology conceptualised and conceived predominantly during early 1995 as part of my Masters treatise at Sydney University - for references see below as well as the paper on pain and inflammation elsewhere on this site.

Melzack R (1999) From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain Supplementation 6; S121-S126

Newport DJ, Nemeroff CB (2000) Neurobiology of post traumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 10; 211-218

Goldstein JA (2004) Tuning the Brain. Principles and practice of neurosomatic medicine. The Hawthorn Press New York

Grossberg S (2000). The complimentary brain: unifying brain dynamics and modularity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 233-246

The Dorsal Root Ganglion, the Intervertebral Foramen and Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy

by Martin Krause, 1995 & 2000.

The efficacy of manual therapy interventions has been extensively criticised in recent years .Serious charges of physiotherapy induced conviction of disease (nocebo) leading to chronicity have been raised. Paradoxically, the omission of higher centre processing in the design of double blind investigations, results in a dichotomy of interpretation which, either justifies the determination of inefficacy or alternatively, predicts an important role for higher centre involvement during the selection and application of manual therapy techniques. Specifically, the sensory-discriminative and motivational-affective responses require dissemination if hypotheses regarding the efficacy of manual therapy treatment, for acute radicular pain, are to be made. Currently, the majority of pain research has established immune-nervous system responses associated with post-traumatic inflammation rather than repair. Recently, dysfunction of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG), which lies in the intervertebral foramen (IVF), has been implicated in both the genesis and chronicity of radicular pain. Previously, manual therapy techniques to the IVF, such as traction, have been anecdotally advocated to normalise signs and symptoms in acute radicular pain. Clinicians use the presenting signs and symptoms, to guide their clinical reasoning processes. Additionally, the normalisation of signs and symptoms is used to demonstrate the usefulness of a treatment technique to their clients. Investigations demonstrate higher centre involvement in the reduction of pain and inflammation. Clearly, if the efficacy of manual therapy is to be determined, then the differentiation between a treatment dependent descending inhibition of pain and inflammation, with that of a placebo or nocebo, is required.

INTRODUCTION: HIGHER CENTRE SENSORY-DISCRIMINATIVE AND MOTIVATIONAL-AFFECTIVE SENSORY PROCESSING BY THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Recently, sensory-discriminative (Ploner et al. 1999) and motivational-affective (Vogt et al 1993) pathways for pain have been demonstrated in humans. The main constituents of the sensory-discriminative aspects of pain (Aδ fibre activity) include the lateral thalamic, primary (I) and secondary (II) somatosensory cortices. Conversely, the motivational affective aspects of pain consists predominantly of the medial thalamic nuclei and the anterior cingulate cortex. Importantly, this structural differentiation suggests that the specificity of treatment and the demonstration of efficacy are important aspects in the nervous systems responses to treatment. Frequently, the practitioner uses the normalisation of signs and symptoms to demonstrate efficacy, in addition to guiding their clinical reasoning processes (Higgs & Jones 1995). However, such an approach could be dangerous as it reinforces the conviction of disease and could result in a nocebo effect (Bogduk 1997; Cohen 1995). Hence, what role does the sensory-discriminative aspect of pain have on the motivational-affective response to manual therapy techniques?

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) has demonstrated that higher centres of the nervous system may be actively involved in, the descending inhibition of acute pain and inflammation in humans (Hsieh et al. 1995; Petrovic et al. 1999). Animal investigations of supraspinal opioids found a block in the perception of pain, through a 64% reduction in superficial laminae dorsal horn activity (Gogas et al. (1991) (usually associated with a predominance of nociceptive specific neurones {Lima et al. 1994}), and a 85% reduction in ventral horn activity (usually associated with motor neurones) in animals (Schomburg & Steffens 1991). One source of descending inhibition involves pontine noradrenergic projections, in animals (Janig 1985; Martin et al. 1999; Post et al. 1986; Morgan et al. 1989; Nakagawa et al. 1990; Ren et al. 1990; Proudfit 1992). Although descending noradrenergic inhibition is considered to be an opioid-independent form of analgesia (Proudfit 1992), evidence supports the view that m-opioid and a-2 noradrenergic receptors are functionally linked to pain modulation (Gebhart et al 1994). Higher centres have been implicated in sympathetic responses, to spinal manual therapy techniques, in humans (Petersen et al. 1993; Vicenzino et al. 1998). Plausibly, the sensory-discriminative pathway was involved in the reduction of secondary hyperalgesia, as these techniques were applied to the neck for lateral elbow pain.

Evidence for important motivational-affective responses are from animal investigations which, substantiate the finding that higher centres can act in an antinociceptive manner (Sandkuehler et al. 1995). Importantly, a "behavioural set" has been defined as 'a state of readiness or preparation to receive a stimulus that has not yet arrived, or a state of readiness or preparation to make a movement' (Woodworth 1958 c.f. Dubner & Ken 1999). Therefore, the net effect of descending inhibition in animals from the Locus Coeruleus/Subcoeruleus, Nucleus Raphe Magnus, and Nucleus Gigantocellularis is to "dampen or counteract the cascade of events that ultimately lead to the development of inflammatory hyperalgesia" (Dubner and Ken 1999) (see figure 1). Attention and cognitive factors such as previous experience of manual therapy or possibly even the apparent normalisation of signs and symptoms could modulate noxious stimuli in the primary somatosensory cortex (Bushnell et al. 1999; Dubner & Ken 1999). These motivational-affective responses presumably occur with the interaction of the client and the therapist during the clinical reasoning process.

Together, these investigations represent very powerful arguments for assessment of the signs and symptoms during the clinical reasoning process, thereby involving higher centres in the neuromodulation of pain and inflammation. Additionally, the activation of higher centres through the re-setting of stabilising muscles, after the person receives passive joint mobilisation treatment, may be necessary for even greater involvement of higher centres. Confirmation of motivational-affective responses to treatment would require the use of psychometric pain questionnaires, positron emission tomography (PET) and functional MRI to demonstrate the temporal changes in cerebral activity (Casey & Minoshima 1997; Svensson et al. 1997) before, during and after treatment

ECTOPIC IMPULSE GENERATION IN THE DORSAL ROOT GANGLION (DRG) ANDNEUROGENIC INFLAMMATION IN THE SENSORY NERVE ENDINGS OF THE SINUVERTEBRAL (SNV) NERVE – A ROLE FOR LOCALISATION OF TREATMENT?

To justify an important localised sensory-discriminative response to injury and hence treatment requires an appreciation of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) dysfunction. Inflamed structures demonstrate increased excitability of sensory nerve endings (Raja et al. 1988; Schmidt et al. 1994). A cause of acute radicular spinal pain may be the generation of excessive electrical activity (ectopic impulses) from inflamed structures. Passive joint mobilisations may be useful in the treatment of radicular spinal pain by 'unloading' those structures (e.g. DRG) whose functions include the modulation of ectopic impulse generation. Ectopic discharge can occur in the DRG following damage that occurs distally in the neural pathway and in the presence of endoneural oedema in animals (Howe et al. 1977), and humans (Nordin et al. 1984). Essentially, endoneural oedema of the DRG resulting from compression by extraneural inflammatory exudate (Chatani et al. 1995) in the intervertebral foramen (IVF) generates ectopic electrical impulses (Bandalamente et al. 1987). These ectopic impulses originating in the DRG are thought to propagate into the spinal cord and into peripheral receptor sites (Wall & Devor 1983; Bandalamente et al. 1987). Consequently, the extent of spinal cord sensitisation, oedema and neurogenic inflammation may in some cases be more significant than the physical size of an intervertebral disc (IVD) protrusion (Garfin et al. 1991; Thelander et al. 1992). Interestingly, Bogduk (1997) advocates radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of chronic spinal pain. However, in acute radicular pain it becomes apparent that the DRG is likely to regulate the excitability of the sensory nerve endings (Devor 1999). Therefore, 'unloading' of mechanical compromise (extraneural inflammation) around the DRG in the IVF, by for example traction, could plausibly reduce ectopic impulse generation (see figure 2).

Ectopic impulse generation from the DRG may propagate throughout the innervation of the sinuvertebral (SNV) nerve. The SNV nerve is a peripheral nerve formed by the recurrent branch of the ventral ramus and a branch of the grey ramus communicantes of the somatic and peripheral sympathetic nervous systems respectively (Bogduk & Twomey 1997). Since the SNV nerve does not innervate superficial structures of the body, it may play a sensory-discriminative role such as mechanoception and nociception (Ahmed et al. 1993). Certainly, the types of receptors innervating the ligamentous structures, suggests such roles (Korkula et al. 1985; Weinstein et al. 1988a). Similar to other peripheral nerves, a vasoactive role on blood vessels may be a function of the sympathetic component of the SNV nerve (Appenzeller et al. 1984; Selander et al. 1985; Weinstein et al. 1988b; Zochodne et al. 1990). Importantly, the terminals of the SNV nerve appear anatomically well placed to transmit ectopic impulses to the IVD, posterior longitudinal ligament, Hoffman ligaments, and the dura mater (Weinstein et al. 1988a, Bogduk & Twomey 1997). This increased ectopic impulse propagation increases neurogenic inflammation, possibly at the SNV nerve receptor sites (Markowitz et al. 1989; Xavier et al. 1990; Chatani et al. 1995). Arborization of the SNV nerve terminals can cause neurogenic inflammation in an expanded receptive field (LaMotte et al. 1991). Furthermore, expansion of spinal cord neuronal hypersensitivity may arise from the propagation of ectopic impulses into the spinal cord from the periphery (Wall & Devor 1983). This expansion is called secondary hyperalgesia and possibly explains the severity of referred limb pain, which is a frequent manifestation of radicular pain. Therefore, a dual role of the SNV nerve in the detection of nociception, in addition to the propagation of ectopic impulses to structures of the IVF and spinal canal is plausible. Presumably, specific manual therapy techniques will induce a sensory-discriminative response, which is likely to activate a motivational-affective response that either increases or decreases secondary hyperalgesia depending upon the perceived appropriateness of the treatment.

THE HYPOTHESIS: SPINAL TECHNIQUES AFFECT THE DORSAL ROOT GANGLION (DRG) IN THE INTERVERTEBRAL FORAMEN (IVF)

Clearly the expansion of the hypersensitive receptive field, underlie the importance of investigating the sensory-discriminative aspects of treatment techniques. Variation of techniques to the IVF, such as the type of load (stretch vs. compression, active vs. passive), the position, and the duration are probably detected by SNV nerve terminals, innervating inflamed structures. Since the SNV nerve appears to innervate the DRG itself (Cuartico et al. 1988; Groen et al. 1988), the ramifications of extraneural inflammation in the IVF are vascular compromise inducing intraneural oedema in the DRG. Consequently, intraneural oedema causes ectopic impulse generation, which increases the intensity of the existing extraneural neurogenic inflammation. Hence, an ongoing self-perpetuating cycle of neurogenic inflammation ensues, which potentially impoverishes any regulation in excitability of sensory nerve endings by the DRG. Thus, if a treatment technique affects the vascular compromise (and extraneural inflammation) surrounding the DRG, in the IVF, then a resultant reduction in endoneural oedema in the DRG would interrupt this self-perpetuating cycle of neurogenic inflammation. Significantly, reduced ectopic impulse generation and enhanced modulation of excitability of sensory nerve endings, by the DRG, may substantiate the validity of using the immediate normalisation of signs and symptoms for the determination of the appropriate technique (Larsson et al. 1980; Maitland 1986; Eggertz 1986; Pal et al. 1986; Knutsson et al. 1988) (see figure 3). Thus, any measured changes in sensory-discriminative function may imply an activation of higher centre responses. In turn, the subsequent motivational-affective response may be indirectly determined through autonomic testing of that innervation field (Sandroni 1998).

A MODEL: MECHANICAL TRACTION FOR THE NORMALISATION OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS IN ACUTE RADICULAR SPINAL PAIN

A recent review suggested some people with acute radicular spinal pain responded well to traction with the normalisation of signs and symptoms (Krause et al. 2000). Specifically, to determine an important sensory-discriminative response then the predictive validity of the current model is the normalisation of signs and symptoms within a narrow band of loading tolerance. Since the valid dose of traction would be the normalisation of signs and symptoms, then the inappropriate dose will be the deterioration of signs and symptoms. In considering ectopic impulse generation, 'unloading' of the contents of the IVF (i.e. Nerve Root/Dorsal Root Ganglion/Spinal Nerve, intra-foraminal blood vessels, sinuvertebral nerve) may be a logical explanation for the first observation of the normalisation of signs and symptoms. Reduction in ectopic impulse generation and simultaneously enhanced modulation of inflammation could be expected from the mechanical 'unloading' of the DRG in particular. Similarly, if the inflamed structures comprising the IVF (i.e. IVD, Zygapophyseal joint, Hoffman ligaments, etc) (Groen et al. 1988; Park & Watanabe 1990; Wiltse et al. 1993; Bogduk & Twomey 1997) are 'overloaded', then ectopic impulse generation (Raja et al. 1988; Schmidt et al. 1994) with the deterioration of signs and symptoms can be expected during excessive traction. The normalisation-deterioration of signs and symptoms can be referred to as a two-threshold hypothesis.

The clinical implications of the sensory-discriminative and motivational-affective aspects of pain highlight the importance of differentiating a specific neurophysiological effect from the placebo and nocebo. Clearly the demonstration of efficacy and expectations of outcome are an essential aspect of any treatment protocol. Presumably, some people will deteriorate or not respond to traction at all. In these people, the loading threshold has not been reached or another form of treatment is more appropriate. Importantly, lack of improvement or deterioration may induce a nocebo response. Therefore, the clinical reasoning process needs to identify the responders from the non-responders in a manner, which expedites appropriate treatment. Hence, a correlation with psychometric questionnaires and the temporal aspects of functional MRI and PET diagnostic imaging would be required before conclusions of efficacy are drawn. Since it is unlikely that a person could guess their threshold for their normalisation of signs and symptoms, then a method of investigation for a differentiation of the neurophysiological, placebo and nocebo effect may include the use of the two-threshold hypothesis.

THE VALIDITY OF USING THE NORMALISATION OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The validity of testing procedures underlie the ability of the examiner to make a clinical prediction (Payton 1988). Clinical reasoning uses signs and symptoms to determine the appropriateness of a treatment strategy (Higgs & Jones 1995). However, is the reduction in ectopic impulse generation and the modulation of excitability in sensory nerve endings correlated with the observable normalisation of signs and symptoms? Significantly, the incidence of the normalisation of signs and symptoms is not clear. Therefore, is the normalisation of signs and symptoms useful for making consistent decisions on the appropriateness of treatment technique for acute radicular pain? Finally, does the use of this methodology impart conviction of disease?

The pain response and range of motion (ROM) of straight leg raise (SLR) is a variable used to assess the effects of treatment using traction (Larsson et al. 1980; Eggertz 1986; Mathews et al. 1987; Pal et al. 1986; Tesio et al. 1989). The load and position of the patient have been defined by the improvement in the pain free ROM of SLR (Larsson et al. 1980). During SLR, the direct contact pressure of the DRG against the structures of the IVF (Smith et al. 1993) and tension generated in inflamed nerve roots are thought to cause sufficient ectopic impulse generation to stimulate the reflexogenic drive to the alpha-motor neurones, as demonstrated in animals (Woolf et al. 1994). Clinically, this reflexogenic drive may represent increased muscle activity that reduces ROM. Since ectopic impulse generation from the DRG also propagates into the spinal cord, then neuronal hypersensitivity could explain alterations in signs and symptoms on the contralateral side seen in humans and animals (Larsson et al. 1980; Woolf 1984; Woolf & Swett 1984; Woolf & MacMahon 1985; Woolf & Wall 1986b; Schmidt 1990; Eckert et al. 1999). Confirmation of such findings require, fine needle electromyography (EMG). Obviously, solely comparing ROM of SLR to the opposite side without due consideration of other variables may lead to errors in the clinical reasoning process.

Other variables inferring some validity when correlated with the normalisation of SLR, during treatment, include reduction in pain intensity, normalisation of muscle strength, and restoration of somatosensory evoked potentials (Knutsson et al. 1988). Additionally, improved asymmetric skin temperatures and sensation testing has been demonstrated (Knutsson et al. 1988; Onel et al. 1989). Although, the incidence of the normalisation of signs and symptoms was high, methodological problems exist which suggest caution in the interpretation of these results. Never the less, normalisation of muscle power, skin sensation, skin temperature, and pain intensity may be correlated with ROM of SLR to predict appropriate technique during the clinical reasoning process.

Normalisation of tendon reflexes has been used to assess patients, during auto-traction, and is thought to correlate with the normalisation of conduction along nerve fibres (Larsson et al. 1980; Pal et al. 1986; Knutsson et al. 1988; Onel et al. 1989; Sabbahi & Khalil 1990b). However, hypersensitivity in spinal cord reflexes can cause tendon reflexes to increase or decrease during neurogenic inflammation and ectopic impulse generation (Ferrell et al. 1988; Rees et al. 1994). Evidence for variable hyper- and hyporeflexia during inflammation comes from Hoffman-reflex investigations where increasing stimulus intensity increases the reflex until a given stimulus threshold is reached where a decrease or complete block in the Hoffman-reflex amplitude occurs (Sabbahi & Khalil 1990a). Since inflamed tissues have reduced receptor threshold, then excessive electrical activity during loading may alter reflex activity (Raja et al. 1988). Whether the hypersensitivity of spinal cord reflexes from neurogenic inflammation and ectopic impulse generation represent a decrease rather than an increase in tendon reflex awaits confirmation in the clinical situation. Importantly, this stimulus-dependent phenomenon may explain the deterioration of signs and symptoms when a technique is applied indiscriminately. Paradoxically, rather than demonstrating efficacy, such sensory-discriminative methodology has been seen to impart conviction of disease, which negatively influences the motivational-affective aspects of the pain (Bogduk 1997: Cohen 1995, Zusman 1998). Therefore, clinical reasoning based upon the normalisation of signs and symptoms would only be justified if a reduction in chronicity could be demonstrated. Epidemiology, using large numbers of subjects, would be required to validate these opinions.

RESTORATION OF NERVE CONDUCTION THROUGH THE MODULATION OF NEUROGENIC INFLAMMATION AND CYTOKINE-IMMUNE RESPONSES BY THE DRG AND PERIPHERAL SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM (SNS)

Peripheral nerve injury results in morphological changes in the DRG (Dib-Hajj et al. 1999; Eckert et al. 1999; Ramer et al. 1999). Although these morphological changes relate to chronic constriction, the onset and perpetuation of neurogenic inflammatory responses appear to begin within hours of the acute phase of injury (Schmidt et al. 1994). Notably, the SNV nerve and spinal nerve may represent the peripheral nerves susceptible to constriction irritation. The proposed genesis of these morphological changes are Wallerian degeneration in the periphery releasing nerve growth factor, leukaemia inhibitory factor and Interleukin (IL) - 6 (Ramer et al. 1999). The activation of similar cytokines is also associated with immune responses during exercise induced musculoskeletal damage (Pedersen et al. 1999) (SEE : Immune function and muscle mass or slide presentation for more detail). The disruption of the fibroblast endothelium is considered the 'trigger' for the release of tumour necrosis factor, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8. Subsequently, there is an activation of prostaglandin driven release of Substance P, with its consequential further release of cytokines from macrophages and mast cells, which completes a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation (Groenblad et al. 1991; Rothwell & Hopkins 1995). Generally, inflammation and mast cell degranulation affects blood-nerve permeability and nerve conduction (Harvey et al. 1994). If, the interaction between the DRG and peripheral SNS is responsible for these immune responses during inflammation, then a treatment technique like traction may aid in reducing constriction of the affected peripheral nerves. In turn, the re-establishment of DRG function will enhance the modulation of cytokine activity. It is difficult to conceive any methodology, which may directly image these morphological changes in humans. Interestingly, some of the resultant restitution of nerve conduction is predicted to occur beyond the immediate application of the treatment technique. Therefore, the extent by which manual therapy techniques can prevent such morphological changes from occurring could justify early and appropriate treatment interventions. Certainly, pharmacological investigations have demonstrated greater treatment efficacy when early intervention was instigated (Bhala et al. 1988).

REDUCTION OF VENOUS CONGESTION AND THE MODULATION OF HOMEOSTASIS BY THE DRG IN THE INTERVERTEBRAL FORAMEN (IVF).

Reduction in mechanical irritation from venous congestion around the DRG may be an explanation for the efficacy of a treatment technique such as traction. Cadaveric studies demonstrate that mechanical abnormalities within the spine, such as IVD extrusion, result in dilatation, congestion, and thrombosus of veins contributing to disruption of the vascular endothelium and consequent fibrin deposition (Hoyland et al. 1989). Importantly, intraforaminal blood flow may represent part of the sensory-discriminative function of the DRG. The unusual location of the DRG between the peripheral and central nervous systems has been related to its hypothesised function as a sensor of background information such as homeostasis of the IVF milieu (Devor 1999). Besides location, evidence supporting a homeostatic function of the DRG is the lack of blood-nerve barrier around the cells of the DRG and the highly convoluted nature of its vasculature (Devor 1999). Obviously, sufficient blood flow would be required to detect homeostasis. Arguably, techniques such as traction achieve reduction in mechanical irritation by increasing the space for the intra-foraminal blood vessels of the IVF. Apparently, improved IVF space has been demonstrated by merely positioning a person to reduce their lumbar lordosis (Panjabi et al. 1983). The implications are that the function of the DRG may be susceptible to vascular and mechanical compromise in the IVF. Since venous pressure is quite low, the advocacy of using positions of comfort in acute radicular pain may be justified (Maitland 1986), as the required restitution of homeostasis in the IVF may occur.

Additional explanations for the effectiveness of using the ‘positions of comfort’ or low dose traction reside in the effect of neural irritation from compression at two locations. Besides swelling in the IVF from inflammatory exudate, the zygapophyseal (Z) joint may be swollen and inflamed. Histological changes suggestive of inflammation have been demonstrated in the Z-joint (Cooper et al. 1995). Since the Z-joint represents the posterior aspect of the IVF then presumably some decompression of the IVF may result from stretching of the Z-joint capsule during traction (Krause et al. 2000). Interestingly, nutrient transport to the nerve roots from both the intraneural blood vessels and from diffusion from the cerebrospinal fluid is affected in the intermediate zone between the two sites of compression almost as much as at the compression sites themselves, in rats. Even low pressure (10mmHg) is sufficient to induce a significant reduction in total blood flow possibly from retrograde capillary stasis due to venous occlusion (Rydevik et al. 1984a,b; Olmarker et al. 1989a,b; Cornefjord et al. 1992; Matsui et al. 1992; Takahashi et al. 1993). Clinically, pressure from extruded IVD material, in the IVF, and swelling of the Z-joint may represent a similar situation to the animal model. Importantly, relatively small traction loads or ‘positions of comfort’ may be required to reduce compromise at one site, thus resulting in the restoration of venous flow necessary for any homeostatic function of the DRG in the IVF. Perhaps, ultrasound imaging may be useful for demonstrating alterations in the dimensions of the Z-joint capsule. Certainly, ultrasound has been effective in demonstrating changes to the size or shape of the multifidus muscle which inserts into the Z-joint capsule (Hides et al. 1994). MRI of the IVF, doppler ultrasound of intraforaminal flow and computer modelling may be investigative procedures, of the future, for determining the biomechanical response to the treatment technique.

HEALING: THE ROLE OF THE VASCULATURE AND PERIPHERAL SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM IN THE MODULATION OF NEUROGENIC INFLAMMATION AT THE SINUVERTEBRAL (SNV) NERVE TERMINALS: A MOTIVATIONAL – AFFECTIVE RESPONSE TO SOMATOSENSORY STIMULI?

The sympathetic efferents are postulated to be important to the healing process since the activation of peripheral terminals of sympathetic postganglionic neurones contributes to neurogenic inflammation (Levine et al. 1986). Since emotions and somatosensory inputs profoundly influence the autonomic nervous system, non-invasive autonomic testing has been advocated in people with pain (Sandroni 1998). Sympathetic postganglionic neurones release inflammatory mediators that increase plasma extravasation, including prostaglandins (Coderre et al. 1989; Gonzales et al. 1989; Gonzales et al. 1991; Green et al. 1991a,b). Additionally, under conditions of sympathetic postganglionic neuronal modulation, bradykinin has been found to increase plasma extravasation (Green et al. 1992). Importantly, the interaction between primary afferent nociceptors (associated with the DRG) and sympathetic efferents during inflammation appears to be increased for intact nociceptors with axons travelling in damaged nerve (Sato & Perl 1991). Conversely, the sympathetic postganglionic neurones also release mediators, which decrease plasma extravasation, including neuropeptide Y and noradrenaline (Green et al. 1991; 1992). Apart from modulating plasma extravasation these substances may also interact with endothelial relaxing factor (Greenberg et al. 1991) and platelet-activating factor (Heller et al. 1994) in the blood vessels. Significantly, agents that enhance synovial plasma extravasation have been demonstrated to decrease tissue injury during inflammation (Coderre et al. 1991). The mechanisms by which sympathetic nerves decrease tissue injury are unclear. However, an increased plasma extravasation would be expected to reduce the concentration of inflammatory substances through the facilitation of venous drainage thereby improving healing (Heller et al. 1994) at the terminals of the SNV nerve. These animal investigations suggest that in addition to non-invasive autonomic testing, the motivational-affective responses need to be monitored using psychometric pain questionnaires.

DURATION OF EFFICACY: THE 'SILENCING' OF ECTOPIC IMPULSE GENERATORS COULD LEAD TO A PROLONGED EFFECT SIMILAR TO LOCAL ANAESTHETICS.

The relief of pressure from extraneural inflammatory compromise at SNV nerve receptor sites surrounding the DRG could 'silence' ectopic impulse discharges. Ideally, this 'silencing' would last for a similar duration to that demonstrated by local anaesthetics. Local anaesthetics 'silence' the neurones at the site of ectopic impulse generation for a period outlasting the pharmacological effect of the local anaesthetic (Devor et al. 1992). It has been hypothesised that any silencing of ectopic discharges should allow the autoinhibitory interneurones of the spinal cord to recover from the neurotoxic effects of increased large diameter afferent bombardment (Sugimoto et al. 1990; Dubner 1991). Alternatively, this ‘silencing’ may provide the sensory-discriminative pathway an opportunity to activate powerful descending inhibition of pain and inflammation. A reduction in ectopic discharge has been shown in cats when the compression stimulus was removed (Howe et al. 1977). Thus, if a technique reduces endoneural oedema by assisting in the removal of extraneural inflammatory exudate from around the DRG and SNV nerve, then this may explain any normalisation of neurological signs and symptoms for a duration outlasting the period of the technique. Importantly, the demonstration of such temporal responses, once the biomechanical stimuli of our techniques has been removed, would highlight the overwhelming influence of the neurophysiological processes in healing.

CONCLUSION

Reduced mechanical irritation of the DRG in the IVF may be responsible for the immediate and long lasting effects of the appropriate treatment for acute radicular pain, in some people. Consequently, reduced ectopic impulse generation and enhanced modulation of pain and inflammation should be accompanied by the normalisation of signs and symptoms. Sensory-discriminative and motivational-affective nervous system responses are likely mechanisms required for the prolonged normalisation of signs and symptoms. Clearly, future investigations into the efficacy of manual therapy, requires the incorporation of higher centre processing into the methodology. Vascular changes as a result of inflammation are probably modulated by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Improved blood flow allows the restoration of the homeostatic function of the DRG. Additionally, the modulation of the excitability of sensory nerve terminals, by the DRG, involves its interaction with the SNS. Enhanced modulation of prostaglandin activity through the interaction of the DRG and SNS with the cytokine-immune system at the sites of innervation of the SNV nerve may restore nerve conduction. The two-threshold hypothesis for the dose of traction could represent a novel experimental method, as it is unlikely that a person can guess the threshold of their normalisation of signs and symptoms. A promising investigative model, using the dose of traction, psychometric analysis, computer modelling, in addition to diagnostic imaging, represents a potential methodology for unravelling the mysteries of radicular pain. The effect of appropriate early intervention to the incidence of chronicity requires investigation, since the validity and precise incidence of the normalisation of signs and symptoms during the treatment of acute radicular pain has not been clearly established. Hereby, charges of physiotherapy induced conviction of disease leading to chronicity can be addressed.

Original conception : January - June 1995

Presented : WCPT and IFOMT, Yokohama 1998 - key note address

Published : Manual Therapy : 2000

Revised : 7 March 2022 and 30 April 2024