- are they all the same?

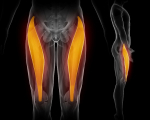

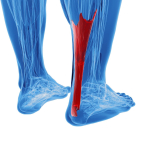

How often have you heard of people injuring their hamstring, only to have treatment involving soft tissue massage, taping, stretching and ultrasound? With a bit of luck they may have had a neural stretch thrown in for good measure!! Yet, what has the physiotherapist ascertained from their clinical reasoning to take the usual prototypical approach to all sports injuries? No doubt they have had some success in the past with such an approach, since most acute injuries will get better anyway. However, what of the clients speed of recovery and subsequent sporting performance, let alone their rate of re-injury?!

Variables which need to be considered when assessing a musculoskeletal injury

A more precise approach to the 'torn hamies' would be to use clinical reasoning. In the subjective examination, the frequency of injury needs to be ascertained. Is it a first time or does it occur regularly? How does this relate to the years of experience of the athlete? If it is a first time and the person has had years of experience in the sport, then you must ask yourself why it happened. What was the mechanism of injury and was it severe enough to warrant the amount of swelling and bruising you encounter in your physical examination? Does this correlate with the severity of the disability described? If the mechanism of injury doesn't provide sufficient information, then analyse the time of onset, i.e. early or late in the game to get an idea if it is a problem of insufficient warm up and visco-elasticity or a problem of endurance and reduced performance with the onset of fatigue. This information will be critical for your exercise prescription. If the athlete is a novice to the sport then exercise prescription must include sport-specific elements in the psycho-cognitive-motor domain. These sport specific elements will also vary depending upon the position a player has. In soccer, for example the winger tends to run in bursts and predominantly in straight lines, whereas the defenders tend to run sideways and backwards, whilst the mid-fielders tend to be the technical agility magicians. Additionally, what are the kicking characteristics of the position played? Similarly, the midfield player at AFL spends a lot of time down low scrambling for the ball and can run up to 20km in a game, whereas the goal kicker tends to sprint short distances, kick and reach high to take a mark. Each of these players will load their hamstrings in a different manner. Finally, did the injury involve the stretch-shortening cycle of a forward moving leg, or the energy transfer function during the concentric stance push-off phase? The physiotherapist who doesn't ask the right questions, will continue to under-perform and not meet the clients full potential and expectations. Clearly, by narrowing the scope of their intervention, the inexperienced physiotherapist using a recipe based approach may never realise the full potential of their involvement . Merely, having the excuse that they know little about that precise sport suggests a lack of communication with their clients and hence a lost opportunity to learn the precise nature of the players needs to reach their goals. Therefore, not all 'torn hamies' are the same and treatment should be oriented towards the unique nature of the injury.

Importantly, the timing of relaxation define the efficiency of repetitive muscle use

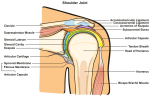

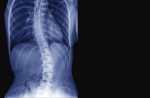

As eluded to, the biomechanical consideration of an eccentric versus concentric injury should also be taken into consideration. In the eccentric open kinetic chain scenario, the neural dynamics and lumbo-pelvic stability of the opposite leg need to be taken into consideration. Clinically, it is very common to see a tight hamstring and SLR (neural restriction of sciatic nerve mobility) on one side, with a tight quadriceps and PKB (neural restriction of femoral nerve mobility) on the opposite side. This is a classic example of Newtons Third Law of equal and opposite forces in action. It also may represent altered pelvic symmetry. An anterior tilted pelvis may lead to a tight rectus femoris and reduced hip extension, thereby either reducing the stride length and/or induce pelvic rotation backwards on the stance side, rather than forward rotation on the swing side. Hence, the shortening elements of peripheral muscles can dictate the rotation of the pelvis which leads to excessive movement in the lumbar spine. Ideally, the gluteal and iliopsoas muscles provide a powerful synergy on the stance leg which allows optimal foot placement of the swing leg, thus reducing the strain on the decelerating function of the hamstring. At foot strike, the lateral hamstrings form a sling across the pelvis to the contralateral thoracolumbar fascia, whilst the medial hamstrings form a functional synergy with the hip adductors and ipsilateral internal and contralateral abdominal oblique muscles. Clinically, it is important to ascertain the functional integrity of these synergistic muscles, as well as the stability of the symphasis pubis and ilium. Excessive anterior rotation of the ilium can potentially lead to anterior hip pain due to impaction from the acetabulum (hip socket) on the femur (ball), as well as a tight piriformis with SIJ and sciatic nerve irritation. Sciatic nerve irritation can create ectopic impulse generation increasing hamstring muscle tension and thereby reducing stretch-shortening agility. Furthermore, the geometry of the anteriorly rotated ilium reduces the ability of the gluteus maximus to contract properly. Add, SIJ irritation then quite frequently, the upper gluteus maximus will become tight and go into spasm whilst the lower gluteus maximus is completely inhibited. Either scenario will alter the timing of gluteal : hamstring activation in favour of the hamstring. Lack of inferior gluteus maximus contraction together with reduced relaxation time of the hamstring muscles will lead to premature fatigue and risk of injury in the hamstrings. The anteriorly rotated ilium also places strain on the L4 lumbar vertebrae by rotating it contralaterally, which may stretch the L4/5, L5/S1 nerve root. Such irritation can not only lead to excessive pain but also to more subtle changes in adverse neural tension (ANT) resulting in calf and hamstring tightness, reduced dorsi flexion during the swing phase, as well as reduced hip extension during stance phase. Similarly, the ANT can lead to excessive forefoot strike with it's inherent risks for lateral ankle stability. The latter scenario will have an impact on the timing between the erector spinae, inferior gluteal and superior hamstring muscles.

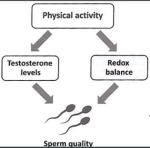

Treatment strategies should include muscle energy techniques for anterior ilial rotation, lack of hip extension, and SIJ - L4 dysfunction. Additionally, joint mobilisations, soft tissue massage, taping for 'unloading' the hamstrings, McConnell taping for the gluteus maximus, ultrasound, electrotherapy, may be used. Finally, sport specific exercise regimes which define not only the stage, severity, irritability and stability of the dysfunction but moreover reflect the mechanism of injury (misuse, disuse, overuse, abuse) as well as the precise demands of the sport should be implemented. The return to sport regime should reflect the loading capacity of the hamstrings at each stage of recovery. Biomechanically, the hamstring muscles (semitendinosis, semimembranosis, biceps femoris) peak force occur simultaneously around terminal swing during sprinting, which suggests that they are vulnerable to injury in this phase (Schache et al 2012, Med Sc Ex Sp, 44, 4, 647-658). Hence, rehabilitation for the hamstring in a sprinter eventually requires high intensity, high velocity exercise training to be functionally successful. Swiss Ball, theratubing, bike riding and Pilates Reformer are some good basic exercises for the hamstring in the initial phases of rehabilitation. Architectural changes changes of the biceps femoirs long head have been shown to differ between concentric (muscle shortening) exercise versus eccentric (muscle lengthening) exercise. In the latter muscle fascicle length was considerably longer, however these changes reversed again after 28 days of de-training (Timmins et al 2015, Med Sc Sp Ex, 48, 3, 499-508). Hip stability exercises will also be of paramount importance, particularly in ballistic multidirectional sports such as soccer, where rotation and lateral stability need to combine with forwardly directed power. Moreover, specific exercises for sacral torsion and ilial nutation may also be required. Localised vibration of the hamstrings have been shown to increase knee extensibility over an 8 week period (Hoshang Bakhtiary et al 2011, AJP, 57, 165-171). Whole Body Vibration is also used at Back in Business Physiotherapy in North Sydney to achieve hamstring length and strength. Nutritional issues such as Magnesium supplementation, creatine and carbohydrate-protein formulation may also need to be addressed.

Cognitive and meta-cognitive reasoning should define the precise nature of the condition

Filtering multiple hypothesis formation through cognition and meta-cognition

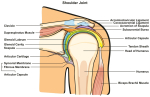

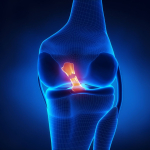

ACL injury and surgical repair using hamstring grafts

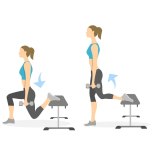

Interstingly, limbs which have had an ACL reconstruction using semitendinosus muscle have been found to have biceps femoris (lateral head) {BFlh} muscle with shorter fascicles and greater pennation angles under 25% MVIC load compared with the contralateral uninjured side. Furthermore, their eccentric loading capacity was reduced (approx 16%), when tested using the Nordic Protocol, even though isometric strength deficits were negligible (Timmins et al 2016, Med Sc Sp Ex, 48, 3, 337-345). This has major clinical implications when undertaking post operative knee rehabilitation, especially when considering that the hamstring muscles act, along with the ACL, to reduce the anterior 'draw' (glide) of the tibia on the femur, as well as act to control the rotation of the tibia on the femur. Supine bridges - bilateral and unilateral can be used with or without a step can be used to activate both the gluteals and hamstrings, with progression to a swiss ball. Simple sideways and backward stepping off a step maintaining body weight on the stance side can work the posterior stabilising kinetic chain whilst maintaining a continuous eccentric-concentric load on the quadriceps. Modified lunges with a forward tilting body at the hips will also engage the posterior kinetic chain, as will a modfiied 'downhill skiing' position squat. in both instances once the static position is reached the movement becomes a forward and backward movement, horizontal to the floor, rather than up and down. Ultimately, exercises such as the 'bobbing duck' can be employed.

It is important to remember that even a grade II strain of the hamstrings can take 28 days to recover. More severe strains can take up to 6 months. Additionally, the myofascial trains should not be overlooked suggesting a total body approach to rehabilitation and repair. Further reading on exercises for hamstrings injuries.can be found elsewhere on this site

Link to

General health and the Immune system in Sport

Link to Instructional Design - Clinical Reasoning

by Martin Krause (2010)

Back in Business Physiotherapy North Sydney

Last update : 28 April 2022