Establishment of an exercise dose-response outcome for weight loss in obese and overweight adults - a literature review

A dose - response effect has been observed during progressive exercise. Notably, even a small exercise dose of 400Kcal/week (40-50% of recommended guidelines) results in a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity (Dube et al 2012, Med & Sc in Sp & Ex, 44, 5, 793-799). Moreover, as little as a 7 day vigorous (60 min/day 85%HRmax) exercise is sufficient not only to improve insulin sensitivity and fat oxidation but also to favorably alter adipokine secretion, independent of changes in body weight or composition (Kelly et al 2012, Med Sc Sp Ex, 44, 1, 69-74). One half of all Americans over the age of 65 are leading the global rate of blindness. Moderate (walking) and vigorous (running) exercise, through increasing energy expenditure, reduce the risk of cataracts. This is highly likely to be the result of anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity from increased levels of HDL. (Williams, PT 2013 Med Sc Sp Ex, 45,6, 1089-1096).

by Martin Krause, May 2003, updated 27 July 2013

Introduction

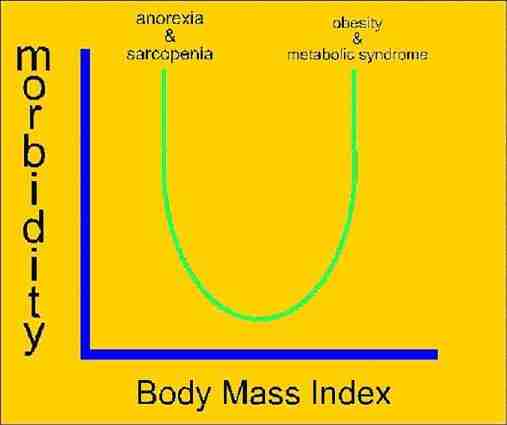

Obesity and overweight is a significant public health problem leading to chronic diseases and health conditions (Jakicic, Clark, Coleman, Donnelly, Foreyt, Melanson, Volek, Volpe 2001). Exercise is considered to have anti-inflammatory effects in sub-clinical iinflammatory conditions such as obesity. Obesity, especially that associated with visceral adipose tissue accumulation, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diseases such as dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitis and cardiovascular disease. These conditions are consistent with increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNFα, C-reactive protein (CRP), leptin, and resistin, as well as reduced anti-inflammatory markers such as IL-10 and adiponectin. Regular exercise, both aerobic and resistance training, promote anti-inflammatory effects including the reduction in visceral adipose fat mass, increased production and release of muscle-derived anti-inflammatory 'myokine', an effect on adipose tissue that reduces hypoxia and local adipose tissue inflammation, in addition to decreases in leukocyte adhesion and cytokine production by endothelial cells (Brunelli et al 2015, Med Sc Sp Ex, 47,10, 2207-2215). Therefore, weight loss is an important consideration in reducing these morbidity factors. This paper defined 2000Kcal/week energy expenditure, through exercise, as a minimum dose to effect significant weight loss. Importantly, the convenience of exercise as well as lifestyle behavioural modification were shown to improve long term exercise adherence.

Background

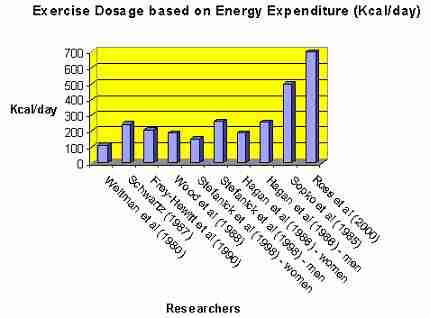

Figure 1: Previous dosage used by various researchers to compare weight loss through exercise in obese, dyslipidemic and overweight adult males and females (source: Ross, Freeman and Janssen (2000).

Several investigators have demonstrated weight loss through energy expenditure (figure 1). However, these investigators concluded that dietary restriction was more conducive to weight loss than exercise prescription. Yet several research methodological errors occurred. These included a vast mismatch in the calorific energy restriction through diet compared with energy expenditure through exercise in all except the 2 investigations of Ross et al (2000) and Sopko et al (1985). In one case the diet restriction of 1200Kcal/day was compared with the energy expenditure of 245Kcal (Schwartz 1987). Another example of mismatch were in the comparative investigations of Hagan et al (1986) where the overweight women and men had a diet restriction of 945Kcal/day and 1705Kcal/day respectively, compared with 190Kcal/day and 255Kcal/day energy expenditure in the exercise groups respectively. In fact, with the two exceptions mentioned, the average calorific deficit induced by exercise was 28% of the calorific shortfall induced by diet. Needless to say the majority of investigators concluded that weight loss through dietary calorific restriction was more efficacious than weight loss through exercise. Thereby, these investigators concluded the superiority of diet over an exercise regime. Furthermore, lack of adherence to exercise was suggested as the problem. However, analysis of these results demonstrate that, even with 100% adherence, approximately 50% more weight should have been lost than was actually lost regardless of intervention regime. Therefore, Ross, Freeman and Janssen (2000) concluded that no justification can be made for the non-inclusion of exercise into any weight loss programme. Importantly, the inclusion of investigations to determine effective exercise dose based on calorific expenditure requires a methodology, which monitors the confounding variable of calorific dietary consumption.

Figure 2: Weight loss through energy expenditure from exercise.

Interestingly, despite the methodological problems described, the importance of calorific metabolic energy expenditure for weight loss can be seen (figure 2). The majority of investigators used an average exercise duration of 22.75 minutes. However, 2 groups of researchers account for the calorific outliers by using 43 minutes (Ross et al 2000) and 65 minutes (Sopko et al 1985) exercise durations. Apparently, longer periods of exercise resulted in greater calorific energy expenditure. More precisely, 700Kcal energy expenditure requires that subjects walk on a treadmill for about 60 minutes at 70% of maximal heart rate (~60%V o2max ) (Kraemer, Volek, Clark, Gordon, Puhl, Koziris, McBride, Triplett McBride, Putukian, Newton, Haekkinen, Bush and Sebastianelli 1999).

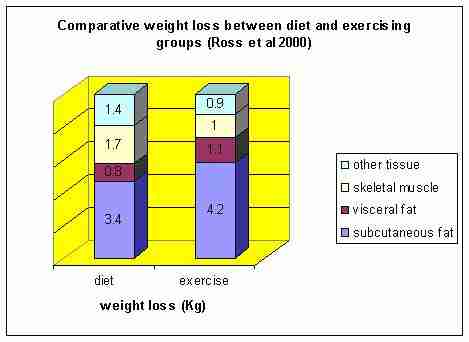

Figure 3: Fat loss through energy expenditure from exercise

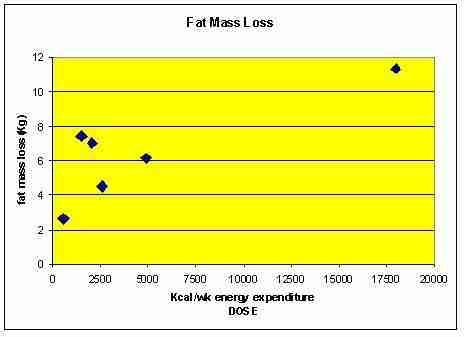

A similar trend to figure 2 can be seen in figure 3 whereby greater exercise duration results in greater fat loss. Interestingly, the 700Kcal/day dose resulted in a 6.1kg fat loss, whereas the weight loss was 7.5kg. An MRI analysis of the composition of weight loss revealed comparatively greater visceral and subcutaneous fat loss through exercise than with diet (figure 4). Significantly, several investigators have demonstrated that reductions of visceral fat, reduces insulin resistance in men (Janssen, Fortier, Hudson, Ross 2002; Ross, Dagnone, Jones, Smith, Paddags, Hudson, Janssen 2000; Ross 2003). Therefore, these results suggest that the quality of weight loss may be more conducive to reduction in co-morbidity factors through exercise than dietary calorific restriction alone.

Figure 4: Comparative weight loss composition between dietary caloric restriction and calorific expenditure through exercise (Ross et al 2000).

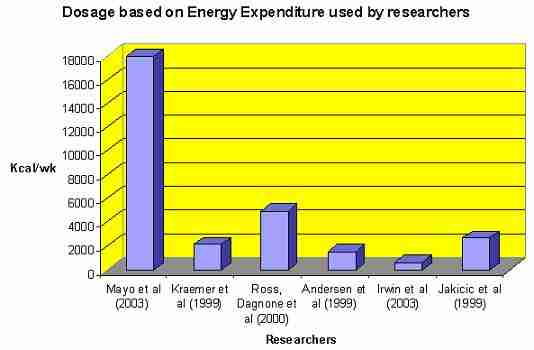

Selection of papers to an exercise dose for a weight loss response outcome

A large range of energy expenditure over varying time periods, have been used to investigate the effects of exercise on weight loss. Mayo, Grantham and Balasekaran (2003) used 30 obese male army recruits on a 4 month training programme. Kraemer et al (1999) used 35 overweight men on a 12 week programme. Ross et al (2000) used 52 obese men over a 12 week programme. Andersen, Wadden, Bartlett, Zemel, Verde, Franckowiak (1999) used 40 obese women on a 16 week programme with a 1 year follow up. Interestingly, this study demonstrated significant maintenance of weight loss at the 1year follow-up by including a lifestyle behavioural approach to exercise. This may be a novel method of maintaining exercise adherence. Jakicic, Winters, Lang, and Wing (1999) also addressed the problem of exercise adherence by including an 18 month behavioural weight loss programme to 3 different exercise groups of 148 overweight females. These investigations generally used subjects in their 20's and 30's. However, the investigation by Irwin, Yutaka, Ulrich, Bowen, Rudolph, Schwartz, Yukawa, Aiello, Potter, McTiernan (2003) selected a group of 173 overweight post menopausal women to undertake a 12 month exercise trial. This exercise group undertook moderately intense sports/recreational activity, which most frequently included 176min/wk of walking. Conversion tables were used to calculate an average 600Kcal/wk of energy expenditure. All except the investigation of Mayo et al (2003) used randomized control design for assigning subjects into various comparative groups. Instead, Mayo et al (2003) used a non-recruit population matched for age and anthropometric characteristics. These investigations were chosen due to

- their methodological thoroughness,

- statistical analysis of variance generally across more than one intervention group,

- clear data presentation

- low drop – out rate,

- population sample spread of young males, women, men and post menopausal females,

- the common ability to use energy consumption to investigate dose (figure 5).

Importantly, “overweight” was defined as >=24kgm2 BMI by Irwin et al (2003), body weights 20%-70% higher than ideal body weight by Jakicic et al (1999) and BMI = 32.8kgm2 by Kakicic et al (1999) suggesting that weight loss through exercise programmes can be used across a population of people with overweight or obesity problems. Finally, with the exception of Mayo et al (2003) whose subjects used the army canteen, all the investigations chosen had strict dietary controls.

Figure 5: Exercise prescription based on calorific dose.

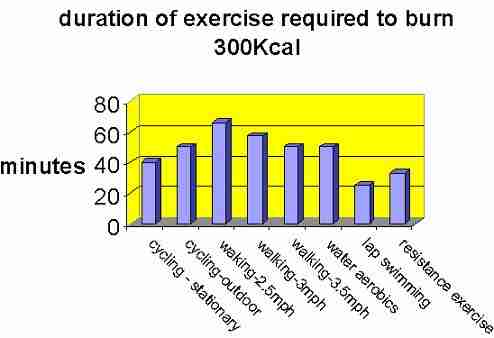

Figure 6: Duration of continuous activity for 300Kcal energy expenditure in a 200lb adult (source Jakicic et al 2001).

Tabulated data provided by the ACSM working group (Jakicic et al 2001) demonstrates the minutes of exercise required for 300Kcal of energy expenditure for adults with a body weight of 200lbs during various activities (figure 6). Interested readers should refer to the original table for other body weight comparisons. Importantly, exercise duration and intensity can be prescribed, which can be converted into energy expenditure. However, both duration and intensity may be considered as inverse dose characteristics. For example, an energy expenditure of 700Kcal/day, 3 days per week, appears to be sufficient to reduce weight and improve insulin sensitivity (Jakicic et al 2001). Alternatively, this would require a lesser intensity of 1 hour walking at 2.5m.p.h (4km/hr), 7 days per week. Interestingly, lap swimming burns more calories sooner, suggesting that non-weight bearing activities may result in greater exercise intensity.

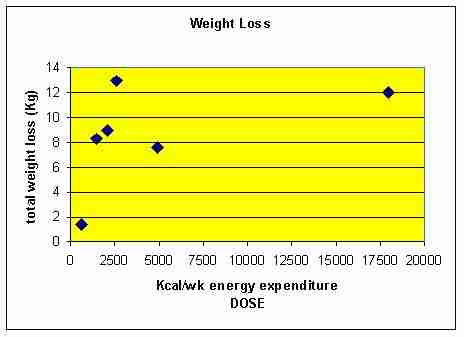

Figure 7: Energy expenditure through exercise versus weight loss.

A threshold in the vicinity of 2000Kcal/wk is sufficient to reduce weight, yet greater energy expenditure leads to greater weight and fat loss (figure 7 & 8). Although the average drop-out rates were low in these investigations, problems with exercise adherence are conceivable if the weekly programme takes too long.

Figure 8: Fat mass loss post exercise vs energy expenditure

Figure 9: Fat free mass (FFM) loss post exercise vs energy expenditure

The least fat free mass (FFM) loss occurred in the group of young army recruits whose exercise adherence was not based on voluntary effort. The outliers in figures 7, 8 and 9 represented army recruits whose training regime time totaled 446 hours in 16 weeks (average ~ 4 hours/day). The young age of these subjects may account for the lack of FFM loss. These investigators demonstrated a FFM loss only occurred with weight reductions exceeding ~11kg (Mayo et al 2003).

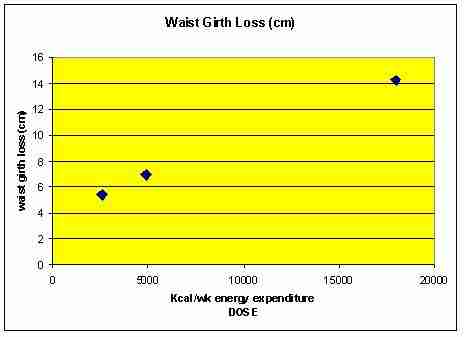

Figure 10: Reduction in waist girth demonstrated by Jakicic et al (1999), Mayo et al (2003), Ross et al (2000)

Excess fat deposition in the abdomen region is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes than is obesity per se (Blair, Kohl, Barlow, Paffenbarger, Gibbons, Marcera 1995; Ross 2003). Indeed, the reduction in waist circumference with the 700Kcal/day exercise prescription resulted in improved insulin sensitivity in obese men (Ross et al 2000). Again, the army recruits demonstrated greatest change through greater energy expenditure.

Exercise programme adherence and long term outcomes

The previous investigations demonstrate significant weight loss in response to exercise which uses at least 2000Kcal energy expenditure per week. Importantly, a behavioural lifestyle intervention is recommended, as improvement gains after a 16 week exercise intervention programme were maintained at a 1 year post exercise follow-up (Andersen et al 1999). Irwin et al (2003) used a similar behavioural lifestyle intervention with success over 12 months, however no follow-up data was provided. Jakicic et al (1999) measured the adherence to their behavioural lifestyle and exercise programme during an 18 months trial. Additionally, they compared 3 exercise groups:

- short bout (SB): 20min/day initially, then gradual increase to 40min/day by week 9 divided into multiple 10 minute bouts per day

- long bout (LB): 20min/day from week 1-4 , then 30min/day from week 5 through to week 8, and finally 40 min/day of continuous exercise for the duration of the study.

- Short bout + exercise equipment (SBEQ): exercise prescription identical to the SB group but they were also provided with a motorized treadmill.

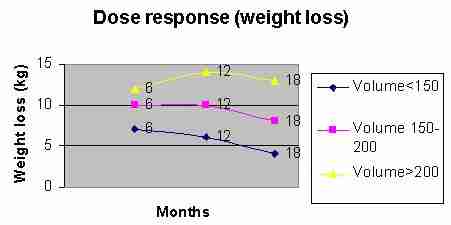

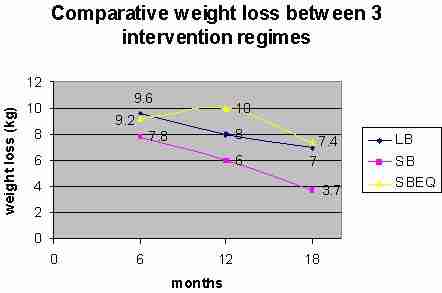

As expected, the greater volume of exercise resulted in greater weight loss (figure 11 & 12). Surprisingly, the SBEQ group did considerably better at 12months (figure 13) suggesting better exercise adherence. Perhaps the novelty and convenience of the treadmill may have improved the motivation, comfort and convenience to exercise. Similar to the observation made with the energy consumption during swimming, it may be the comfort of the shock absorbing characteristics of the treadmill, which is an important consideration in overweight and obese people. Alternatively, the pacing characteristics of the treadmill and lap swimming may be a motivating factor to attain an exercise goal, which more closely resembles the energy expenditure required to lose weight.

Figure 11: weight loss based on volume of exercise (min/wk). The greater volume of exercise resulted in greater weight loss

Figure 12: Energy expenditure per week vs weight loss. The greater the energy expenditure, the greater the weight loss

Figure 13: Comparative weight loss between exercising groups. Convenience of exercise appeared to be an important factor in exercise adherence and weight loss. The multiple short bout group using a treadmill had greater weight loss than the equivalent multiple short bout group without a treadmill

Implications of research to health outcome

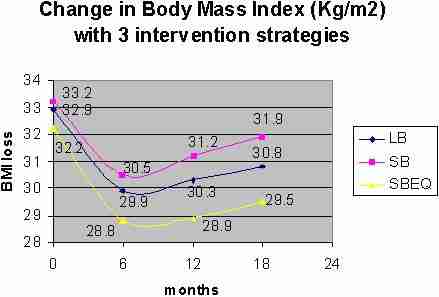

A body mass index (BMI) > 25kg/m2 is considered to represent a significant health risk including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Shaper, Wannamethee, Walker 1997). Although these results did not result in BMI <25kg/m2, at 6 months there was a positive trend in that direction in this population of overweight women aged between 25 and 45. However, this trend began to reverse after 6 months (figure 14). The investigators correlated this reversal in trend to a loss of adherence to the exercise programmes. Importantly, these results highlight the need for convenience when prescribing an exercise regime to the overweight – obese population.

Figure 14: Reductions in Body Mass Index (BMI) at 6, 12 and 18 months.

In other investigations, high intensity exercise (RPE 15.4) versus low intensity exercise (RPE 11.1) for a 16 week walking programm was shown to reduced regional body fat by 47 vs 11cm2 and abdominal visceral fat content by 24 vs 7cm2 (Irving et al 2008) . Further reductions in visceral fat were reported by the same authors with 8 months of vigorous jogging (~20miles/week). This is significant as visceral fat is directly correlated with the progression of glucose intolerance to type II insulin resistant diabetes. Interestingly, moderate intensity exercise (500Kcal) energy expenditure was shown to improve postprandial dyslipidemia in people diagnosed with metabolic syndrome (Mestek et al 2008). This finding wasn't found in healthy subjects, suggesting that even moderate amounts of activity can have large impacts on a critical risk factor for morbidity.

Risk factors associated with exercise

Certain significant risk factors do exists when prescribing exercise to people who are by definition overweight – obese. These include the co-morbidity conditions such as hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes, stroke or heart attack in people with cardiovascular disease. Fortunately, even in exercise regimes without weight loss, serum markers associated with these complications (Sharper et al 1997), such as fat and glucose metabolism were reduced (Duncan, Perri, Theriaque, Hutson, Eckel, Stackpoole 2003). Additional risk reducing changes included reduced systolic blood pressure and increased peak O2 consumption, as well as improved serum cholesterol and triglycerides (Ross et al 1999). However, these changes may take time (e.g. 6 months [Jakicic et al 1999]) and therefore these risk factors need to be monitored and balanced with the potential benefits. Gradual increases in the training regime as described previously are warranted to reduce these risks. Of the 148 subjects who participated in that programme only 6 retired due to medical reasons (Jakicic et al 1999). It has been suggested that exercise resulting in energy deficits > 700Kcal/day may result in lean tissue loss in addition to fat (Mayo et al 2003). However, obese men who expend 700Kcal/day by walking for 12 weeks reduced total fat by 6.1kg with a preservation of skeletal muscle (Ross et al 2000). No significant benefit was demonstrated in regimes, which involved more vigorous resistance training (Andersen et al 1999; Wadden, Vogt, Andersen, Bartlett, Foster, Kuehnel, Wilk, Weinstock, Buckenmeyer, Berkowitz, Steen 1997). Importantly, for sedentary overweight-obese individuals, a diet combined with a lifestyle programme of moderate intensity physical activity can facilitate weight loss, enhance weight management and improve cardiovascular disease profiles (Andersen et al 1999). Therefore, risks may be reduced through progressive incremental increases in the duration of exercise whilst maintaining moderate exercise intensity.

Conclusion

It would appear that the exercise dose selected has to be commiserated with exercise adherence. The minimal dose required to affect weight loss is in the order of 2000Kcal/wk. Ideally, this would include a regime whereby the individual's lifestyle is not disrupted. Indeed, these investigations suggest that the convenience of the exercise as well as meaningfulness (behavioural modification) to overall health and well - being play an important part in adherence to the exercise programme beyond a 4 month regime. Unfortunately, even with 18 months of periodic follow up and monitoring of the exercise regime some regression in weight loss was seen.

References

Andersen RE, Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Zemel B, Verde TJ, Franckowiak SC (1999) Effects of lifestyle activity vs structured aerobic exercise in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA , 28 , 4, 335 to 340

Blair SN, Kohl HW, Barlow CE, Paffenbarger RS, Gibbons LW, Marcera CA (1995) Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. JAMA , 273 , 1093 to 1098.

Duncan GE, Perri MG, Theriaque DW, Hutson AD, Eckel RH, Stackpoole PW (2003) Exercise training, without weight loss, increase insulin sensitivity and postheparin plasma lipase activity in previously sedentary adults. Diabetes Care , 26 , 3, 557 to 562

Frey-Hewitt B, Vranizan DM, Dreon DM, Wood PD (1990) The effect of weight loss by dieting or exercise on resting metabolic rate (RMR) in overweight men. International Journal of Obesity , 14 , 327 to 334

Hagan RD , Upton SJ, Wong L, Whitman J (1986) The effects of aerobic conditioning and/or caloric restriction in overweight men and women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise , 18 , 87 to 94

Irwin M, Yutaka Y, Ulrich C, Bowen D, Rudolph R, Schwartz R, Yukawa M, Aiello E, Potter JD, McTiernan A (2003) Effect of exercise on total and intra-abdominal body fat in post menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA , 289 , 3, 323 to 330

Irving BA et al (2008). Effects of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40, 11, 1863 to 1872

Jakicic JM, Clark K, Coleman E, Donnelly J, Foreyt J, Melanson E, Volek J, Volpe S (2001) Appropriate intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise , 33 , 12, 2145 to 2156.

Jakicic JM, Winters CMS, Lang W, Wing RR (1999) Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women: a randomized trial. JAMA , 282 , 16, 1554 to 1560

Jannsen I, Fortier A, Hudson R, Ross R (2002) Effects of an energy restrictive diet with or without exercise on abdominal fat, intermuscular fat, and metabolic risk factors in obese women. Diabetes Care , 25 , 3, 431 to 438

Kraemer WJ, Volek JS, Clark KL, Gordon SE, Puhl SM, Koziris L, McBride JM, Triplett McBride TN, Putukian M, Newton RU, Haekkinen K, Bush JA, Sebastianelli WJ (1999) Influence of exercise training on physiological and performance changes with weight loss in men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise , 31 , 9, 1320 to 1329

Mayo M, Grantham JR, Balasekaran G (2003) Exercise induced weight loss preferentially reduces abdominal fat. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise , 207-213

Mestek et al (2008) Aerobic exercise and postprandial lipemia in men with the metabolic syndrome. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40, 12, 2105 to 2111

Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones P, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R, Janssen I (2000) Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men: a randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine , 133 , 2, 92 to 103

Ross R, Freeman JA, Janssen I (2000) Exercise alone is an effective strategy for reducing obesity and related comorbidities. Exercise and Sports Science Reviews , 28 , 4, 165 to 170

Ross R (2003) Does exercise without weight loss improve insulin sensitivity? Diabetes Care , 26 , 3, 944 to 945

Schwartz RS (1987) The independent effects of dietary weight loss and aerobic training on HDLs and apolipoprotein A-I concentrations in obese men. Metabolism , 36 , 165 to 171

Shaper AG, Wannamethee GS, Walker M (1997) Body weight: implications for the prevention of coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus in a cohort study of middle aged men. BMJ , 314 , 1311 to 1317

Sopko G, Leon AS, Jacobs DR (1985) The effects of weight loss and exercise on plasma lipids in young obese men. Metabolism , 34 , 227 to 236

Stefanick ML, Mackey M, Sheehan N, Ellsworth N, Haskell WL, Wood PD (1998) Effects of diet and exercise in men and postmenopausal women with low levels of HDL cholesterol and high levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. New England Journal of Medicine , 339 , 12 to 20

Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Andersen RE, Bartlett SJ, Foster GD, Kuehnel RH, Wilk J, Weinstock R, Buckenmeyer P, Berkowitz RI , Steen N (1997) Exercise in the treatment of obesity: effects of four interventions on body composition, resting energy expenditure, appetite, and mood. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology , 65 , 2, 269 to 277

Weltman A, Matter S, Stamford BA (1980) Caloric restriction and/or mild exercise: effects on serum lipids and body composition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 33 , 1002 to 1009

Exercise Intensity, Inflammatory Signaling, and Insulin Resistance in Obese Rats

DA SILVA, ADELINO S. R.; PAULI, JOSÉ R.; ROPELLE, EDUARDO R.; OLIVEIRA, ALEXANDRE G.; CINTRA, DENNYS E.; DE SOUZA, CLAUDIO T.; VELLOSO, LÍCIO A.; CARVALHEIRA, JOSÉ B. C.; SAAD, MARIO J. A.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 42(12):2180-2188, December 2010.

doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e45d08

Abstract:

Purpose: To evaluate the effects of intensity of exercise on insulin resistance and the expression of inflammatory proteins in the skeletal muscle of diet-induced obese (DIO) rats after a single bout of exercise.

Methods: In the first exercise protocol, the rats swam for two 3-h bouts, separated by a 45-min rest period (with 6 h in duration-DIO + EXE), and in the second protocol, the rats were exercised with 45 min of swimming at 70% of the maximal lactate steady state-MLSS (DIO + MLSS).

Results: Our data demonstrated that both protocols of exercise increased insulin sensitivity and increased insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate 1 and serine phosphorylation of protein kinase B in the muscle of DIO rats by the same magnitude. In parallel, both exercise protocols also reduced protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B activity and insulin receptor substrate 1 serine phosphorylation, with concomitant reduction in c-

N-terminal kinase and I?B kinase activities in the muscle of DIO rats in a similar fashion.

Conclusions: Thus, our data demonstrate that either exercise protocols with low intensity and high volume or exercise with moderate intensity and low volume represents different strategies to restore insulin sensitivity with the same efficacy.

Strength Exercise Improves Muscle Mass and Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Youth

VAN DER HEIJDEN, GERT-JAN; WANG, ZHIYUE J.; CHU, ZILI; TOFFOLO, GIANNA; MANESSO, ERICA; SAUER, PIETER J. J.; SUNEHAG, AGNETA L.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 42(11):1973-1980, November 2010.

doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181df16d9

Abstract:

Introduction: Data on the metabolic effects of resistance exercise (strength training) in adolescents are limited.

Purpose: The objective of this study was to determine whether a controlled resistance exercise program without dietary intervention or weight loss reduces body fat accumulation, increases lean body mass, and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in sedentary obese Hispanic adolescents.

Methods: Twelve obese adolescents (age = 15.5 ± 0.5 yr, body mass index = 35.3 ± 0.8 kg·m

; 40.8% ± 1.5% body fat) completed a 12-wk resistance exercise program (two times 1 h·wk

, exercising all major muscle groups). At baseline and on completion of the program, body composition was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, abdominal fat distribution was measured by magnetic resonance imaging, hepatic and intramyocellular fat was measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy, peripheral insulin sensitivity was measured by the stable-label intravenous glucose tolerance test, and hepatic insulin sensitivity was measured by the hepatic insulin sensitivity index = 1000/(GPR × fasting insulin). Glucose production rate (GPR), gluconeogenesis, and glycogenolysis were quantified using stable isotope gas chromatography/mass spectrometry techniques.

Results: All participants were normoglycemic. The exercise program resulted in significant strength gain in both upper and lower body muscle groups. Body weight increased from 97.0 ± 3.8 to 99.6 ± 4.2 kg (< 0.01). The major part (~80%) was accounted for by increased lean body mass (55.7 ± 2.8 to 57.9 ± 3.0 kg,P <0.01). Total, visceral, hepatic, and intramyocellular fat contents remained unchanged. Hepatic insulin sensitivity increased by 24% ± 9% (< 0.05), whereas peripheral insulin sensitivity did not change significantly. GPR decreased by 8% ± 1% (< 0.01) because of a 12% ± 5% decrease in glycogenolysis (< 0.05).

Conclusions: We conclude that a controlled resistance exercise program without weight loss increases strength and lean body mass, improves hepatic insulin sensitivity, and decreases GPR without affecting total fat mass or visceral, hepatic, and intramyocellular fat contents.

Adiposity, Activity, Fitness, and C-Reactive Protein in Children

PARRETT, ANNE L.; VALENTINE, RUDY J.; ARNGRÍMSSON, SIGURBJÖRN Á.; CASTELLI, DARLA M.; EVANS, ELLEN M.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 42(11):1981-1986, November 2010.

doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0355e

Abstract:

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to examine the relative association of physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), and adiposity with C-reactive protein (CRP) in prepubescent children.

Methods: Forty-five prepubescent children (age = 9.4 ± 1.6 yr; 26 boys) were assessed for adiposity (percent fat) via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, CRF with a peak graded exercise test, physical activity using pedometers, and systemic inflammation via serum CRP.

Results: Adiposity was positively correlated with CRP (body mass index,= 0.61; percent fat,= 0.59,< 0.001), whereas step count and CRF were inversely associated with CRP (= -0.49 and -0.37, respectively, all values < 0.05). Compared across fitness or physical activity and adiposity groups, the low-fit/high-fat and the low-activity/high-fat groups had higher CRP than both low-fat groups. There was also a main effect of physical activity (< 0.01) but not fitness on CRP. Regression analyses revealed that percent fat (ß = 0.59, = 0.002) and physical activity (ß = -0.35, = 0.011) were the only independent predictors of CRP, explaining 16.0% and 10.0% of the variance, respectively.

Conclusions: Adiposity is positively related to serum CRP in prepubescent children, independent of the effects of fitness or physical activity. In addition, physical activity is inversely associated with CRP levels. This research identified habitual physical activity and adiposity as focal points for the design of interventions attempting to reduce chronic systemic inflammation in children.

Myostatin Decreases with Aerobic Exercise and Associates with Insulin Resistance

HITTEL, DUSTIN S.; AXELSON, MICHELLE; SARNA, NEHA; SHEARER, JANE; HUFFMAN, KIM M.; KRAUS, WILLIAM E.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 42(11):2023-2029, November 2010.

doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0b9a8

Abstract:

Purpose: There is mounting evidence that skeletal muscle produces and secretes biologically active proteins or "myokines" that facilitate metabolic cross talk between organ systems. The increased expression of myostatin, a secreted anabolic inhibitor of muscle growth and development, has been associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Despite these intriguing findings, there have been few studies linking myostatin and insulin resistance.

Methods: To explore this relationship in more detail, we quantified myostatin protein in muscle and plasma from 10 insulin-resistant, middle-aged (53.1 ± 5.5 yr) men before and after 6 months of moderate aerobic exercise training (1200 kcal·wk at 40%-55% VO2peak). To establish a cause-effect relationship, we also injected C57/Bl6 male mice with high physiological levels of recombinant myostatin protein.

Results: Myostatin protein levels were shown to decrease in muscle (37%, = 0.042, = 10) and matching plasma samples (from 28.7 ng·mL pretraining to 22.8 ng·mL posttraining, = 0.003, = 9) with aerobic exercise. Furthermore, the strong correlation between plasma myostatin levels and insulin sensitivity (= 0.82, < 0.001, = 9) suggested a cause-effect relationship that was subsequently confirmed by inducing insulin resistance in myostatin-injected mice. A modest increase (44%) in plasma myostatin levels was also associated with significant reductions in the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt (Thr) in both muscle and liver of myostatin-treated animals.

Conclusions: These findings indicate that both muscle and plasma myostatin protein levels are regulated by aerobic exercise and, furthermore, that myostatin is in the causal pathway of acquired insulin resistance with physical inactivity.

Exercise without Weight Loss Does Not Reduce C-Reactive Protein: The INFLAME Study

CHURCH, TIMOTHY S.; EARNEST, CONRAD P.; THOMPSON, ANGELA M.; PRIEST, ELISA L.; RODARTE, RUBEN Q.; SAUNDERS, TRAVIS; ROSS, ROBERT; BLAIR, STEVEN N.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 42(4):708-716, April 2010.

doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c03a43

Abstract:

Purpose: Numerous cross-sectional studies have observed an inverse association between C-reactive protein (CRP) and physical activity. Exercise training trials have produced conflicting results, but none of these studies was specifically designed to examine CRP. The objective of the Inflammation and Exercise (INFLAME) study was to examine whether aerobic exercise training without dietary intervention can reduce CRP in individuals with elevated CRP.

Methods: The study was a randomized controlled trial of 162 sedentary men and women with elevated CRP (>=2.0 mg[middle dot]L-1). Participants were randomized into a nonexercise control group or an exercise group that trained for 4 months. The primary outcome was change in CRP.

Results: The study participants had a mean (SD) age of 49.7 (10.9) yr and a mean body mass index of 31.8 (4.0) kg[middle dot]m-2. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) and mean baseline CRP levels were 4.1 (2.5-6.1) and 4.8 (3.4) mg[middle dot]L-1, respectively. In the exercise group, median exercise compliance was 99.9%. There were no differences in median (IQR) change in CRP between the control and exercise groups (0.0 (-0.5 to 0.9) vs 0.0 (-0.8 to 0.7) mg[middle dot]L-1, P = 0.4). The mean (95% confidence interval) change in CRP adjusted for gender and baseline weight was similar in the control and exercise groups, with no significant difference between groups (0.5 (-0.4 to 1.3) vs 0.4 (-0.5 to 1.2) mg[middle dot]L-1, P = 0.9). Change in weight was correlated with change in CRP.

Conclusions: Exercise training without weight loss is not associated with a reduction in CRP.

Energy expenditure calculation formula

Endurance training and movement efficiency

First Upload : Dec 2003

Last update : 4 November 2015