Neck Pain

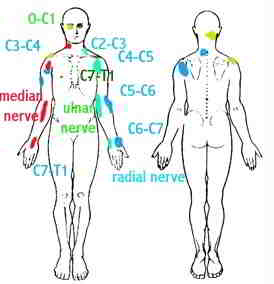

At Back in Business Physiotherapy, in the heart of North Sydney, we treat a variety of neck related disorders. Some people come to us with neck pain and stiffness. Other people see us for headaches, dizziness, and vertigo which is also related to neck pathology. Even, some shoulder, elbow and wrist problems can be associated with neck pathology. This section of our extensive website deals with 'somatic pain', which relates to all movement dysfunctions not related directly to nerve compression or more commonly referred to as a 'pinched nerve'. Please read below for more information on 'somatic neck pain'. For a 'pinched nerve' please see radicular neck pathology.

Somatic referred pain and movement pattern, cervical spine pain and cervical vertigo

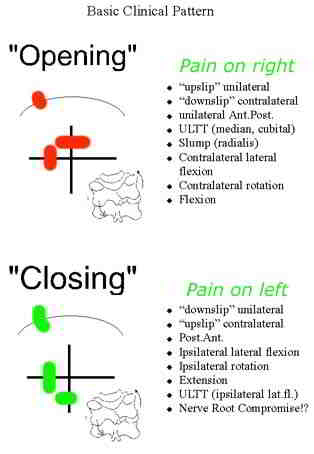

Somatic movement restrictions can have an 'opening' or 'closing' pattern. Generally these conditions respond extremely well to joint mobilisations, Mulligans techniques, Occulomotor reflex patterning exercises, soft tissue massage, dry needling, and exercises for scapula and pelvic symmetry. Additionally, thoracic joint and rib movements usually require assessment for inferior lateral respiratory excursion as well as scapulothoracic mobility. The serratus anterior and trapezius muscles generally require specific attention regarding scapula stability. It should be remembered that somatic movement disturbances will create spasms in some muscles whilst weakness in others. In turn these altered muscle patterns place dysfunctional and asymmetrical loading on the joints.

Cervical Kinesthesia and Occular Reflexes

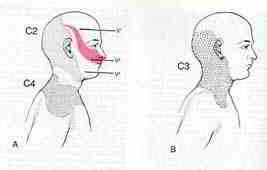

Basic somatic referral patterns

somatic referral due to neurogenic inflammation

Headache - cervicogenic

Cervical Proprioception

-

Clinical aspects of proprioceptive dysfunction have not been researched extensively (Kristjansson 2005)

-

Proprioception is a complex neurophysiological pathway which plays a small but important role in motor control (Gandevia & Burke 1992)

-

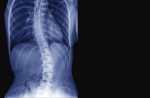

The cervical spine has great mobility at the expense of mechanical stability and a close neurophysiological connection to the vestibular and occular systems (Gimse et al 1996)

-

Perception drives the motor responses. Motor strategies and 'feed forward' preparatory responses are instigated by the CNS to drive the PNS. The CNS stores sensory perceptions in memory. However, sensory conflict may arise when incoming disturbed proprioceptive information is unexpected leading to altered 'efference-afference copy'

-

This hierarchical model has been criticised as it does not explain reactions to novel tasks, nor can the memory bank store all the information needed for complex co-ordinated motor tasks required to solve for the control of multiple 'degrees of freedom' problem proposed by Bernstein (1967)

-

Treatments built into hierarchical ways of thinking (Knott & Voss 1968) have been criticised for being too passive because therapeutic interventions were modelled on facilitation and inhibition rather than function training (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2001)

-

Systems theories examine the functioning of the whole, where self organisation occurs based on principles of physics whereby constraints within an organism, a task and the environment determine which movement strategies are best for each individual as a whole (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2001) - integration of neuro-musculo-skeletal with vestibular, occular and immune.

-

Clinically, treatment needs to be functionally meaningful and task dependent to appeal to the clients perceptions and cognitions.

Phylogenetics

- When the vertebrates evolved in the ocean, the whole body, including the head, formed a spindle-like unity to enable fast swimming. Spatial orientation was served by peripheral vestibular and visual systems

- About 350million years ago when vertebrates climbed onto the land, to be able to survive, their head had to be able to move freely on the rest of their body

- The first rudimentary head on neck motion was a nodding action occurring at 0/C1

- However, this wasn't enough and development of the dens axis enveloped by the ring of the atlas followed (Wolff 1998)

- Last major development took place at C2/3 which facilitated coupling of movements

- These bony developments were accompanied by distinct development of the musculature of the upper cervical spine to orient the head sensors in space

- A network of mechanoreceptors were developed to provide information of the head in regard to the rest of the body

The Cervical Spine and the Postural Control System

- the vestibular, visual and somatosensory systems

- The semicircular canals used to determine changes in the rate of motion, angular velocity

- The otoliths containing the utricular and saccular maculae provide information on linear velocity and gravity (head tilt)

- Convergence occurs in the vestibular nuclear complex (VNC) via the vestibular nerve and cerebellum

- The vestibulo- and reticular-spinal tracts provide impulse propagation to the trunk & limbs

- The upper cervical mechanoreceptors have indirect inputs into these descending tracts

Visual System & Audition

- Over 1/3 of the brain in primates is devoted to vision (Stein & Glickstein 1992)

- The visual postural system consists of 2 movement - smooth pursuit, saccade, opticokinetic

- The vestibular-ocular reflex (VOR) stabilizes images on the retina

- The position and movement of the head in relation to the rest of the body and eye movements is regulated by the VOR and the much weaker cervico-ocular reflex (COR) where the latter acts on the extra-ocular muscles.

- However, in dysfunctional conditions the COR becomes more active and can be used for differential diagnosis of upper cervical spine proprioception (Neuhuber 1998, Tjell 1998)

The somatosensory subsystem

- Upper cervical spine has an abundance of mechanoreceptors, esp. from the gamma muscle spindles (nuclear bag and nuclear chain fibres) of the deep segmental muscles (Richmond & Bakker 1982), these impulses converge in the central cervical nucleus (CNN)

- The cervical mechanoreceptors have direct inputs to the VNC via the DRG at the C2 and C3 levels which contrasts to inputs from lower spine segments which tapper off to indirect inputs.

- Inputs from lower spinal segments converge onto the cuneatus nuclei and travel from there to the cerebelllum (Neuhuber 1998)

- The CNN has important connections to the VNC. The lateral VNC is the origin of the powerful lateral vestibulospinal tracts which controls muscle tone in the trunk and extremeties (Tjell 1998)

- The cervico-collic reflex (CCR) is mediated through these pathways and probably the medial vestibolospinal tract via the VNC (Peterson et al 1985). The CCR is stimulated by cervical movements and dampens the activity of the VOR and VCR stimulated by the semi-circular canals

The nociceptive system

- The nociceptive system in the upper cervical spine projects onto many cranial afferents of which the trigeminal nucleus and the tractus solitaritus nuclear complex (Vagal nerve) are the most important ones.

- Neuroanatomical research indicates connections from the upper cervical spine to the limbic system (Feil & Herbert 1995; Neuhuber 1998)

- Coordination of movement is mainly the function of the cerebellum, where all spinal and brain stem reflexes directly or indirectly converge (Stein & Glickstein 1992)

- Linear Vestibulocollic Reflex (VCR)

- Little is known about the otoliths

- The otoliths are stimulated by linear accelerations of the head and their inputs have been found to modify both eye and head stabilizing responses (Schor et al 1985)

- Otolith contributions to compensatory eye and neck responses increased with stimulus frequency, but the otolith system alone is unable to produce perfect compensation (Boral & Lacour 1982)

- ? Convergence of canal and otolith input on vestibulospinal neurons combine to provide reflexes to linear and angular acceleration ? (Uchino et al 2000)

- ? Otoliths may have a distinct functional affect during locomotion providing compensatory head pitch movements by the angular VCR during walking and the linear VCR during running ? (Hirasaki et al 1999)

Multimodal Control

- The reflexes appear to be predominant in the frequency of natural locomotion (1.5-2Hz) (Hirasaki et al 1999) and their function is to damp oscillations of the head at higher frequencies (Keshner et al 1999)

- Voluntary responses are observed as anticipatory torques in the neck muscles or responses controlled by the occulomotor reflex

- Above 1Hz mechanical factors (inertial, stiffness and viscoelasticity) become important

- The relative importance of the VCR and CCR for head-neck stabilization is probably dependent upon the degrees of freedom and the postural requirements of the task (Keshner 2005)

Motor Control

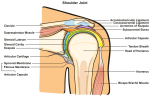

- Complex biomechanical linkage with 20 pairs of muscles capable of performing similar actions -> therefore suggesting some redundancy in the system

- Overall the number of independently controlled muscle elements exceeds the number of degrees of freedom of neck motion -> the extent of functional variability depends upon the task being studied

- Head represents 7% body weight, yet has 20 different muscles directly linking the skull in either side of midline to the vertebral column

- Motions of the head are primarily directed towards orienting and stabilizing the position of the eyes and head in space

- CNS programmes neck muscles in specific directions rather than an infinite variety of muscle patterns

- Muscles organised in layers - outer layer connects skull with the shoulder girdle - deeper layer links the skull with the vertebra

- deepest layer consists of muscles that link the cervical and thoracic vertebrae - The layer of muscles linking the skull to the vertebrae form the long dorsal (splenius capitis, semispinalis capitus and longissimus capitis) and a long ventral (longus capitus) muscle. - > act as a sleeve for the cervical vertebrae eg rotation

- Splenius cervicis, Semispinalis cervicis, longissimus cervicis & longus colli lie deeper, have a small moment arm - > proprioceptive function

- Suboccipital muscles produce extension at the atlanto-occipital joint.

Neck muscle morphometry

- Each muscle differs in it's relative content of fast and slow twitch fibres, angles of pennation, sarcomere length, sites of origin and insertion and the mechanics of action across the individual joints

- Unlike limb muscles where there is a distinct tendonous attachment to bones, many neck muscles had very little tendons at their ends.

- Instead of distinct tendons, many neck muscles have a complex architecture of internal tendons and aponeuroses. (Kamibayashi & Richmond 1998)

Functional Synergies

- One solution to controlling the degrees of freedom (Bernstein 1967) is to organise movement around synergistic muscle torques (Buchanan et al 1989)

- In cats, dissociation between deep and superficial neck muscle activation suggests different neural controllers (Richmond et al 1992)

- Separation of two groups of muscles, one producing the forces necessary to move the head and another to align the head with the terminal target would assist the head-neck controller in meeting multiple criteria or goals (Thomson et al 1994)

- A single action can be accomplished through the activation of agonists and antagonists where the control parameter appears to be the required force vector rather than the specific force lever arm of any particular muscle (Macpherson 1988, 1991) - therefore the specific direction of motion is important

Directional tuning of muscles

- Each muscles preferred direction is unique and consistent amongst subjects (flexion for sternocleidomastoid, ipsilateral flexion for splenius capitis and extension for semispinalis capitis. Trapezius was tuned toward lateral flexion but had the lowest activation and the greatest variability)

- Rotation shifted the maximal activation vectors away from the moment arm direction due to the observation that none of these muscles produce a unique axial rotation torque (Keshner 2005)

- A likely control parameter for the CNS to employ in the selection of which muscle to employ may be contingent upon it's ability to generate a maximal mechanical advantage (Keshner et al 1997)

- Posture affecting the plane of motion of the muscles length and pulling direction may have a greater influence on its contribution than mechanical efficiency (Runciman & Richmond 1997)

- Orientation of the C/S (ie perpendicular or horizontal to earth) was a significant variable in determining the ROM, amplitude and timing of the neck muscles (Statler & Keshner 2003)

Neural Control of the Cervical Spine

- Vestibulocollic (VCR) and cervicocollic (CCR) reflexes, respond reactively to accelerotory and proprioceptive stimuli to maintain the orientation of the head in space (VCR) and the head on trunk (CCR).

- Voluntary responses are those for tracking and acquiring exteroceptive (visual, auditory and olfactory) information and can be used either anticipatorily or pursuit actions

- The normal repertoire of movement responses emerges from combinations of input and output signals (Keshner 2005)

- Vestibulospinal pathways have monosynaptic and disynaptic connections with cervical motor neurons

- Cervical proprioceptive inputs have significant influence on the vestibulospinal signals (Gdowski & McCrea 2000) and together with the reticulospinal neurones have a major influence on orientation and posture through convergence of afferent input which initiates a series of interspinal reflexes

- The VCR alone is not sufficient for purposeful head stabilization in a dynamic environment (Keshner 2005) suggesting that other inputs such as the reticulospinal are also involved.

- Gdwoski & McCrea suggest correct alignment of the head and trunk requires ascending somatosensory inputs. The CCR arises from a stretch of the neck musculature as would occur when turning the body with a fixed head position. This reflex is more complex than a monosynaptic reflex, with evidence of presynaptic inhibition in the CCR response (Banovetz et al 1995)

Neck muscle activation patterns

- Each head motion is executed by a specific muscular pattern that is not repeated in any other direction

- Motor solutions to voluntary head tracking need constant adjustment whereas the VCR and CCR probably only need to stabilize specific cervical joints.

Cervical Vertigo

- Dizziness is the third most common reason to seek medical advice in the USA (Kroenke & Mangelsdorff 1989)

1.8% in young adults to 30% in elderly (Sloane et al 2001) - Up to 80-90% of patients suffering chronic whiplash report vertigo & dizziness (Oosterveld et al 1991)

4 categories of cervical vertigo

- Vertigo : “sensation of irregular or whirling motions, either of oneself or of external objects”

- Near-syncope

- Disequilibrium

-Light headedness (40-50% of attacks are vertigo)

Differential Diagnosis with

- Vertigo (canalolithiasis and cupulolithiasis)

-Prolonged spontaneous - positional vertigo (BBPV) -recurrent attacks - Meniere’s Disease

- Vestibular Neuritis

- Labyrinthitis

- Periplymphatic Fistula

- Bilateral Vestibular Dysfunction

- Central causes

- Vestibular Schwannoma

- Arnold-Chiari Malformation

- Vertiginous Migraine

- Psychogenic Dizziness

- Mal de debarquement syndrome

- Pharmacological

Cervical Vertigo

-

‘spinning of the head’ rather than spinning of the patient, light headedness, tipsy feeling, as a consequence of ‘noise ‘ in the PNS

-

Usually worse in the morning and tappers during the day

-

Associated with neck movements but also with tracking an object or driving a car (Hulse & Holzl 2000)

-

Tend to increase in intensity over time as mechanoreceptors are non-adaptive and their threshold decreases over time if left untreated (Neuhuber 1998)

-

Some people don’t perceive dizziness however they have overall increased muscle tone which may explain why some people go on to develop fibromyalgia

-

In long-standing cases the plasticity of the CNS (Sessle 2000) may make them treatment resistant to traditional manual therapy and techniques employing virtual reality training become important (WiiFit balance exercises), yoga, Tai Chi, etc

-

Visual disturbances although common are not widely accepted due to the lack of verification using conventional opthalmologic instruments (Hulse 1998) – these people complain of blurred vision, reduced visual field, grey spots appearing in the visual fields, temporary blindness, disordered fusion, whole words or whole sentences ‘jump’, double vision but not true diplopia (as with VBI), and reading problems (Hulse 1998)

-

Existence of cervical vertigo is controversial as otoneurological examination are frequently normal

-

Incidence appears to be highest in the 30-50 year old and more common in females

-

The diagnosis of cervicogenic dizziness is based on history, examination, and vestibular function tests

-

Vascular hypothesis - Vertebral artery vasospasms due to close relationship with the sympathetic nerve trunk

However this would be accompanied by serious neurological symptoms such as diplopia, dysarthria, ataxia & motor symptoms

The vertebral artery is at risk in artherosclerosis.-

Degenerative changes in the uncinate processes of the low C/S projecting osteophytes laterally, and/or subluxating superior articular processes (Bogduk 1986)

-

Full rotation of the C1/2

-

Deep fascial bands of cervical muscles crossing the artery, anomalous course of the artery between fascicles of either longus colli or scalenus anterior (Bogduk 1986)

-

-

Neurovascular hypothesis

-

Sympathetic Nervous System

-

C3/4 osteophytes and irritation of superior cervical ganglion ((Tamura 1989)

-

Direct irritation of sympathetic ganglia within fascia of anterior cervical muscles after whiplash

-

Erroneous proprioceptive signalling due to gamma reflexogenic activation of muscle spindles (Johansson & Sojka 1991)

-

However SNS blocks induces vertigo, tendency to fall, horizontal nystagmus & tinnitus, instead of diminishing the symptoms (Barre 1926, Lieou 1928 in Heikkila 2005)

-

-

Somatosensory hypothesis :

-

Disturbed afference – efference copy due to

-

Abnormal sensory input from neck proprioceptors

-

Vestibulo-occular reflex (VOR) stabilizing the visual field

-

Vestibulocollic reflex (VCR) stabilizing the head position

-

Cervicooccular (COR) proprioceptive reflex - helper reflex if the labyrinths have been damaged (Botros 1979), co-operates with the VOR for clear vision – originates in neck and joint proprioceptors

-

Cervicocollic (CCR) proprioceptive reflex – stabilizes the neck and protects from over-rotation and coutneracts the COR, probably generated by the gamma muscle spindles of the deep neck muscles (Hirai et al 1984)

-

Vestibulospinal reflexes – appropriate tone for the neck and body muscles for the purpose of balance

-

-

Impaired kinaesthetic performance was found in people with dizziness/vertigo of cervical origin which may be as a result of lesioning or functional impairment of muscular and articular receptors, or by alteration in afferent integration and tuning (Heikkila et al 2000; Wyke 1979, Taylor & McCloskey 1988)

-

Altered kinaesthetic sensitivity has been implicated in functional instability of joints and their predisposition to re-injury, chronic pain and degenerative joint disease (Revel et al 1991, Hall et al 1995)

-

Postural control and voluntary eye movements were impaired during cervical restriction with a collar (Karlberg et al 1991)

-

Smooth pursuit and saccade abnormalities have been reported in people whiplash (mild – due to altered C/S proprioception {Oosterveld et al 1991}, severe – due to medullary lesions {Hildings et al 1989}), and in people suffering from fibromyalgesia with dysaesthesia (Rosenhall et al 1987)

-

62% of whiplash patients had at least 1 smooth pursuit abnormality at 2 years follow-up (Heikkila & Wenngren 1998)

-

Smooth pursuit was correlated with active ROM function of the C/S (Heikkila & Wenngren 1998; Karlberg et al 1991)

-

Vertigo was reported in 85% of whiplash subjects (Oosterveld et al 1991)

-

Whiplash subjects had less accurate ability to relocate their head in space after active displacement that turned their head away from the reference position (Heikkila & Astrom 1996) – esp. vertical mov’ts -> correlates with hyperflexion/extension injury

-

Signs & Symptoms of Cervical Vertigo

-

Correlating symptoms of imbalance with neck dysfunction

-

Cervical vertigo is characterised by a feeling of unsteadiness when standing and walking rather than rotatory vertigo (Brandt 1991)

-

Accompanied by pain – occipital, temporal, temporomandibular to orbital or forehead region

-

Tenderness on cervical palpation

-

Dizziness and nausea may be provoked by palpation of the lateral mass of the atlas (Scherer 1985)

-

Blurred vision, photophobia, direction-fixed, directional changing positional nystagmus, tinnitus, low frequency hearing loss

-

Imbalance may occur during the Unterberger stepping test

-

Correlating subjective findings (mechanism of onset, history of duration, frequency, area, and intensity) with physical and functional impairment is important in making a diagnosis and monitoring progression

-

Questionnaires

-

Activities Specific Balance Confidence Scale (ASBCS) (Powell & Myers 1995) & Dizziness Handicap Inventory (Tesio et al 1999)

-

Dynamic Gait Index (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2001) & Berg Balance Test (Berg et al 1992)

Physical Assessment

-

Visual Disturbances

-

Smooth Pursuit Neck Torsion Test (SPNT) (Rosenhall et al 1996)

-

Tests the reflex interaction between smooth pursuit system and the proprioceptive system of the cervical spine

-

Velocity of eye movements relative to target object – net gain is calculated; abnormal result is reduced gain in the direction in which the head is rotated

-

When the body is rotated beneath a stationary neck a nystagmus can be induced

e.g. when the trunk is rotated left, the head is in relative right rotation, the COR helps the VOR to stimulate eye movements to the left in this position, but for teleologic reasons, in order to look forward, the saccadic system moves the eyes to mid point. The VOR with the aid of an overactive COR moves the eyes again to the left inducing a right-directional nystagmus (Tjell 1998, Tjell & Rosenhall 1998)

-

-

Dix – Hallpike manoeuvre for BPPV

The patient is in long sitting with the head rotated 45degrees to the side to be tested, then the patient is moved quickly into supine with the head in 30degrees of extension over a pillow under the rib cage, during which the eyes are observed for nystagmus for the posterior semicircular canals

85% of BPPV are upward rotating due to the posterior semicircular canals -

Cervicocephalic kinaesthetic sensibility (position sense + movement sense)

“kinaesthesia is a sensation which detects and discriminates between the relative weight of body parts, joint positions, and movements, including direction, speed and amplitude” (Newton 1982) -> the qualities that are supposed to be the result of proprioception-

Target matching is used to relocate the natural head posture (NHP) or to actively relocate a set point in range (Kristjansson et al 2003) in the transverse and saggital planes

-

Studies have demonstrated reduced relocation accuracy in whiplash patients (Heikkila & Wenngren 1998) but variable results in insidious neck pain (Kristjansson et al 2003)

-

60% sensitivity and 80% specificity (Kristjansson – unpublished work 2002)

-

Movements on the transverse plane stimulate mainly the semicircular canals, those in other planes stimulate the utricular otoliths which are sensitive to gravitational changes (Taylor & McCloskey 1990)

-

Slow movements test cervical proprioception due to the inertia of the cupula in the semicircular canals

-

An important aspect of proprioception is moment-to-moment feedback from tracking fast and unpredictable movements -> ‘the fly’ computer program with a Fastrak device is used for such determination (Kristjansson et al 2003, 2004)

-

Treatment

-

Positive affects have been reported for manipulative treatments (Cronin 1997, Galm et al 1998; Hulse et al 2000)

-

Both acupuncture and manipulation reduced dizziness/vertigo, neck pain and improved head repositioning error (Heikkila et al 2000)

-

Postural training with a significant eye-neck coordination component (Revel et al 1994) and vestibular component (Yardley et al 1998) have been shown to improve posture and dizziness

-

Multimodal approach advocated (Bracher et al 2000)

-

Recruitment of deep cervical flexors in neutral head and shoulder position (Jull 2000)

-

Loss of cervical lordosis in chronic whiplash patients (Kristjansson & Jonsson 2003) due to weak deep cervical flexors of the upper cervical spine (Jull 2000) and deep cervical extensors of the lower cervical spine (Kristjansson 2005)

-

Adequate movement control through range of motion

-

Determine whether global or segmental (upper, mid, low) stability has been lost

-

If segmental then try to move areas below and above the unstable segment keeping the latter stable – cognitive control

-

Next step is to recruit global and local stabilizers which most effectively move the dysfunctional segment under active control in a specific direction – the patient can be taught to only move the decontrolled segment through controlled ROM or move the whole cervical spine

-

The patient is specifically taught to control inner range and to move eccentrically from inner range to mid range and in some cases outer range (depending upon functional task which requires reinstating) (Kristjansson 2005)

-

There has been little research to the effectiveness of treatment strategies aimed at improving neuromuscular control and head carriage in the cervical spine

-

Revel et al (1994) conducted an 8 week eye-neck co-ordination exercise and awareness of movement with significant improvements in neck pain

Olafsdottir & Helgadottir (2001) conducted an ‘awareness through movement’ Feldenkreis program. After 4weeks significant improvements in NHP was detected (5.22deg + 1.79 vs 3.32 + 1.27 after treatment), additionally significant improvements in the Northwick Park Disability Index occurred using a 100mm VAS (Leak et al 1994)

Cognitive VOR training

-

Adaptation – resetting or retuning the VOR

-

Particularly good for unilateral lesions (hypofunction)

-

Must incorporate movement of the head and visual input

-

Takes time – requires 1-2 minutes practice with error signal

-

Context specific –need a wide range of frequencies i.e. head velocities and variety of positions - no distraction

-

Physiological/Behavioural mechanisms

-

Sensory re-learning to change/substitute sensory strategies during functional tasks

-

Can bias strategies away from vertigo side or towards it use and drive compensatory processes

-

Body scan - teach client to attend to various inputs and switch back and forth to those

-

Remove or alter some inputs during a task e.g. eyes open/shut, foam, vibration, head tilts

-

Behavioural strategies as coping mechanisms

-

Learn how to move without triggering symptoms (if adaptation and habituation don’t work)

-

Learn how to lessen the symptom experience via education, relaxation strategies

-

Habituation

-

Habituate repeated exposure to noxious stimulus to bring about neural changes to reduce sensitivity to the stimulus

-

Identify the source of conflicting sensory information i.e. vestibular, visual, somatosensory

-

Design movements based on those reproducing symptoms (1-4 movements, 2-3x each, 2-5x day)

-

Performed quickly enough through sufficient range to reproduce mild to moderate symptoms – increase this as habituation increases

-

Rest between each movement to allow symptoms to subside (approx. 1 minute)

-

May take up to 4weeks to notice changes

-

Do exercise for up to 2months intensively then gradually reduce them

-

Precautions in elderly with choice of movement

go to: radicular referred pain

Updated 29 September 2012