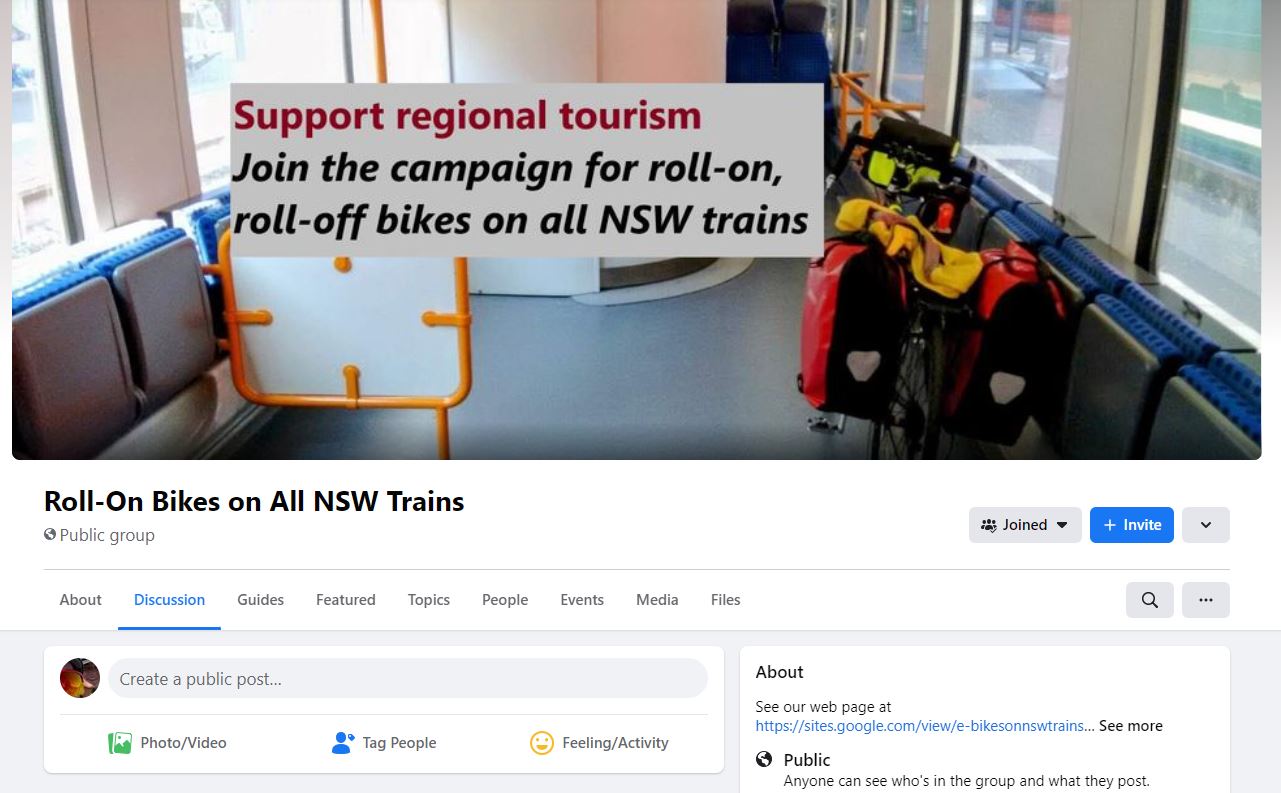

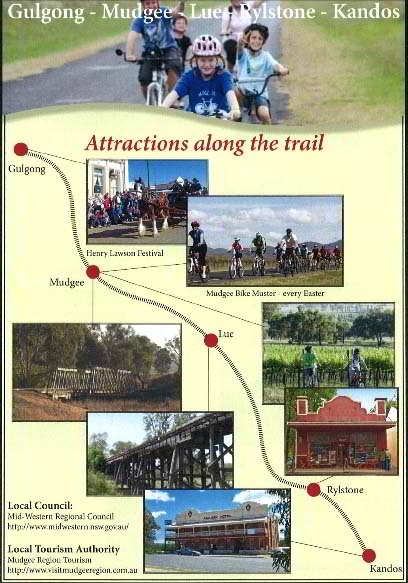

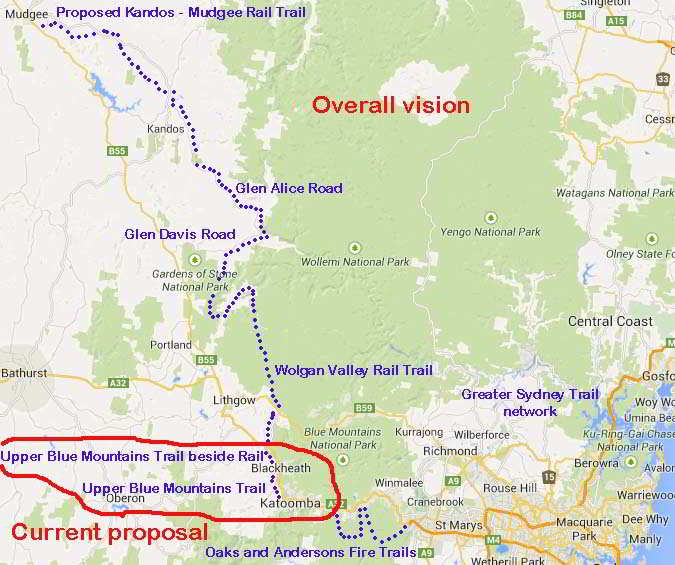

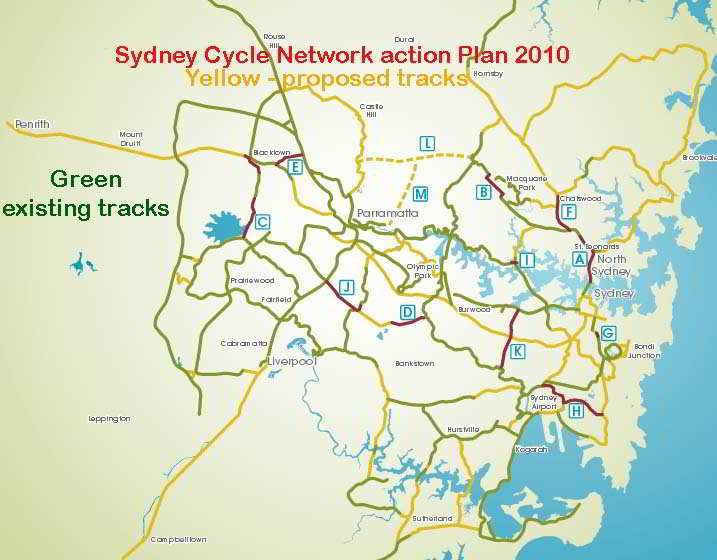

Overall vision is connecting the Sydney cycling network with Bathurst, Orange, Dubbo and Mudgee via the World Heritage listed Blue Mountains and Wollemi Wilderness. In 2020, the Central West bike Trail was established, as was the remaining link across the Blue Mountains. Now, the Newnes (Wolgan Valley) Rail Trail needs to be connected with the Kandos to Mudgee Rail Trail or simply a Cycle Trail parallel to the abandoned railway line.

ie connecting "the Dubbo Sky to the Sea"

(Martin Krause)

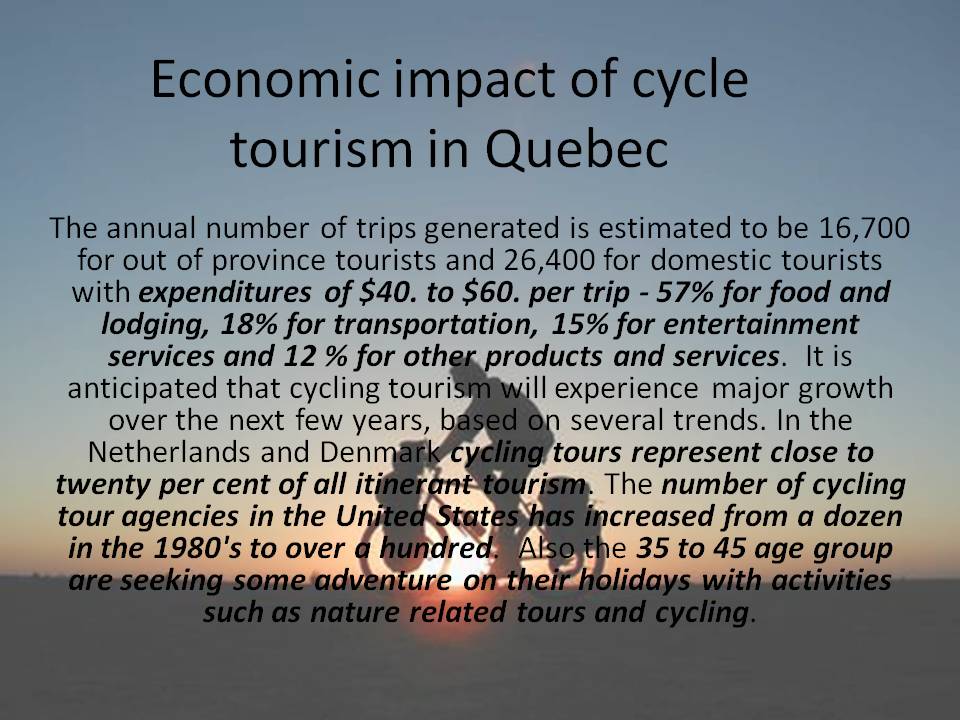

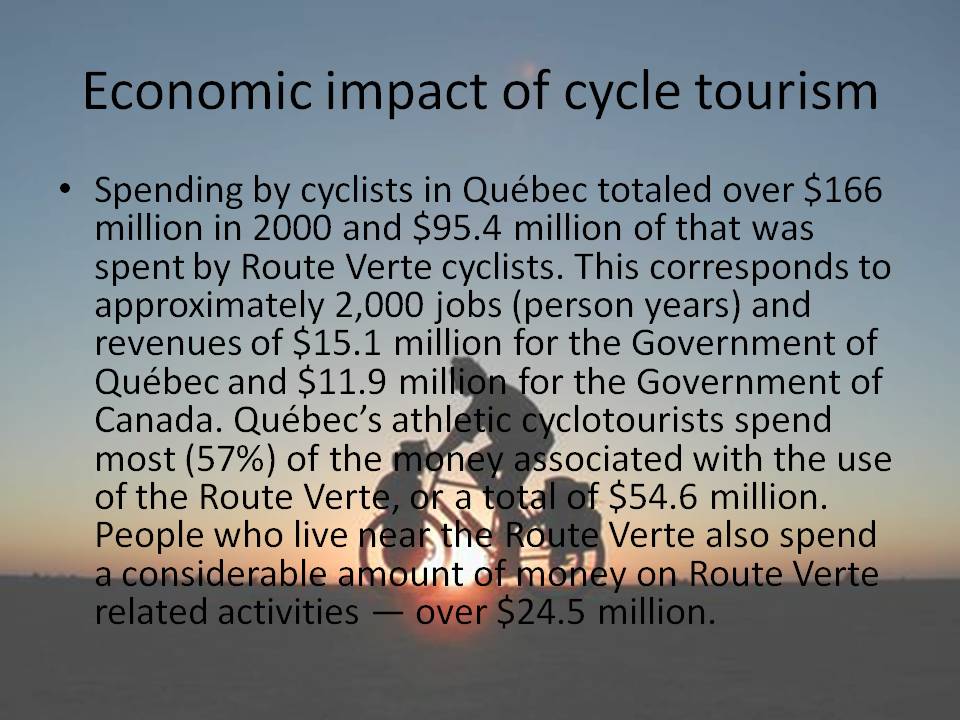

This concept was originally conceived whilst pack cycling the Rail Trails of the Route Verte in Quebec in 1998. In 2015, the Mountains to the Sea concept was adopted and analysed in British Columbia by the Squamish community, as part of the Vancouver to Whistler pack cycling trail.

"Total spending in Squamish attributable to mountain biking totalled

nearly $2.1 million over the period June 4 to September 17, supporting

an estimated $1.9 million in new economic activity (GDP)."

https://www.mbta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/FINAL-Squamish-EI-Study-Dec-15.pdf

"A majority (55%) {of cyclists} had household income levels greater than $80,000. As a datapoint 31% of all BC outdoor recreationalists had household income levels greater than $ 80,000. Mountain biking visitors were generally in line with all tourists to Canada going on guided tours (59% had incomes of greater than $100,000)"

https://www.pinkbike.com/news/economic-impacts-of-mountain-biking-tourism-2014.html

After a quarter of a century of fighting - a miracle appeared on the front page of the AFR in 2021

On 20 October 2021, the Federal Australian Treasure, Josh Freydenburg, appeared on the front page of the Australian Financial Review, declaring the $6.3 Billion Australian cycling economy. The report was created by EY. It highlighted the following :

- 5.8M or 29% of adults aged 18 to 90 – the estimated number of Australian adults who spent money on cycling-related goods and services.

- 1.7M new bikes were sold

- 28% of new bike sales were children’s bikes.

- $990 – the average annual spend on cycling related goods and services.

- Fitness was the primary motivation for cycling.

- Recreational road cycling is the most popular form of the activity making up 69% of respondents.

- 52% said they ride a stationary or indoor trainer.

- Between 2019 and 2020 the annual number of bike imports increased from 1.2M to 1.7M.

- State and Local Governments spent $428M on cycling infrastructure and promotion in 2020.

Link to report : https://bicyclingaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-Australian-Cycling-Economy_October-2021-Updated.pdf

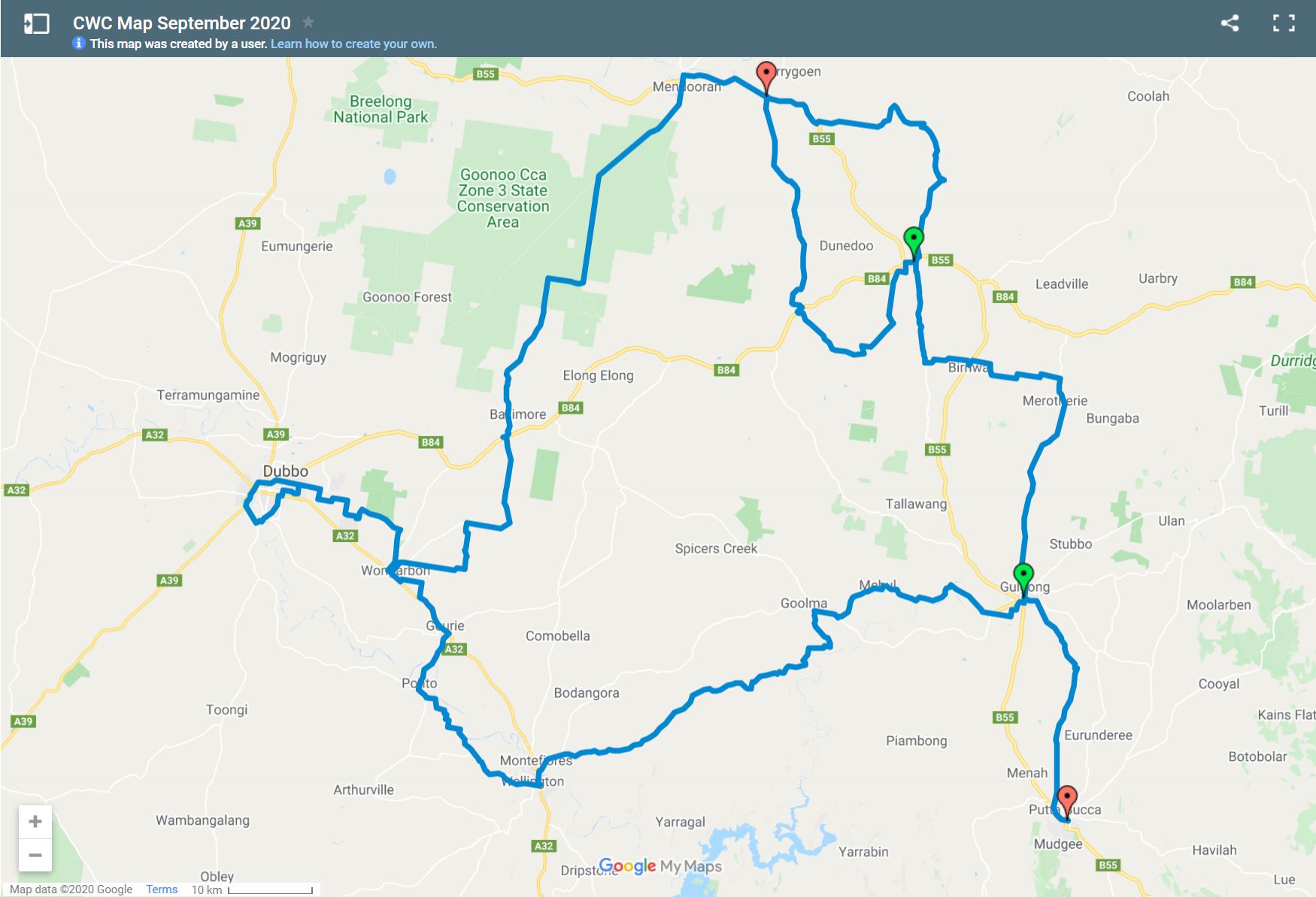

Second miracle in a month - 13 November 2021

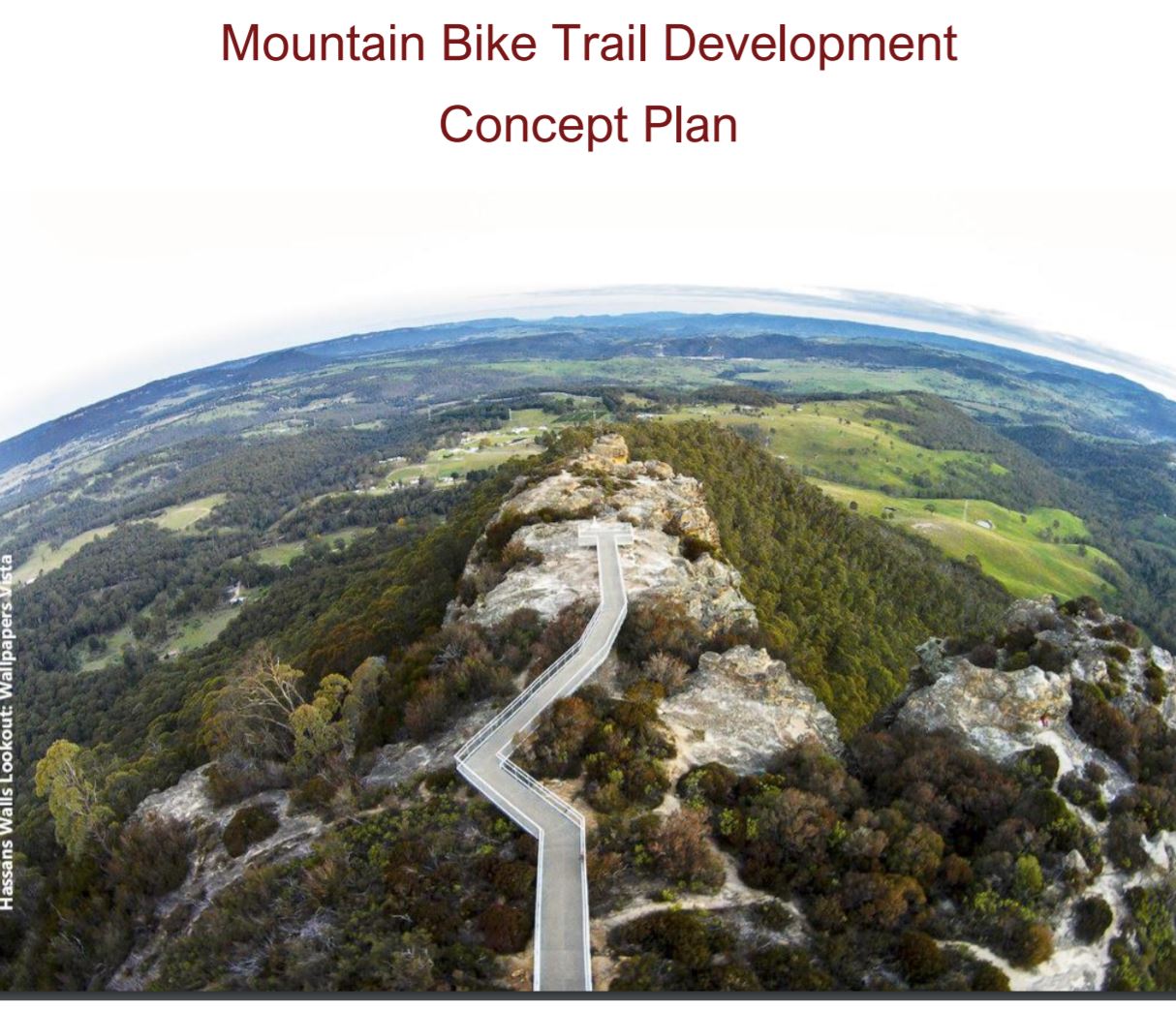

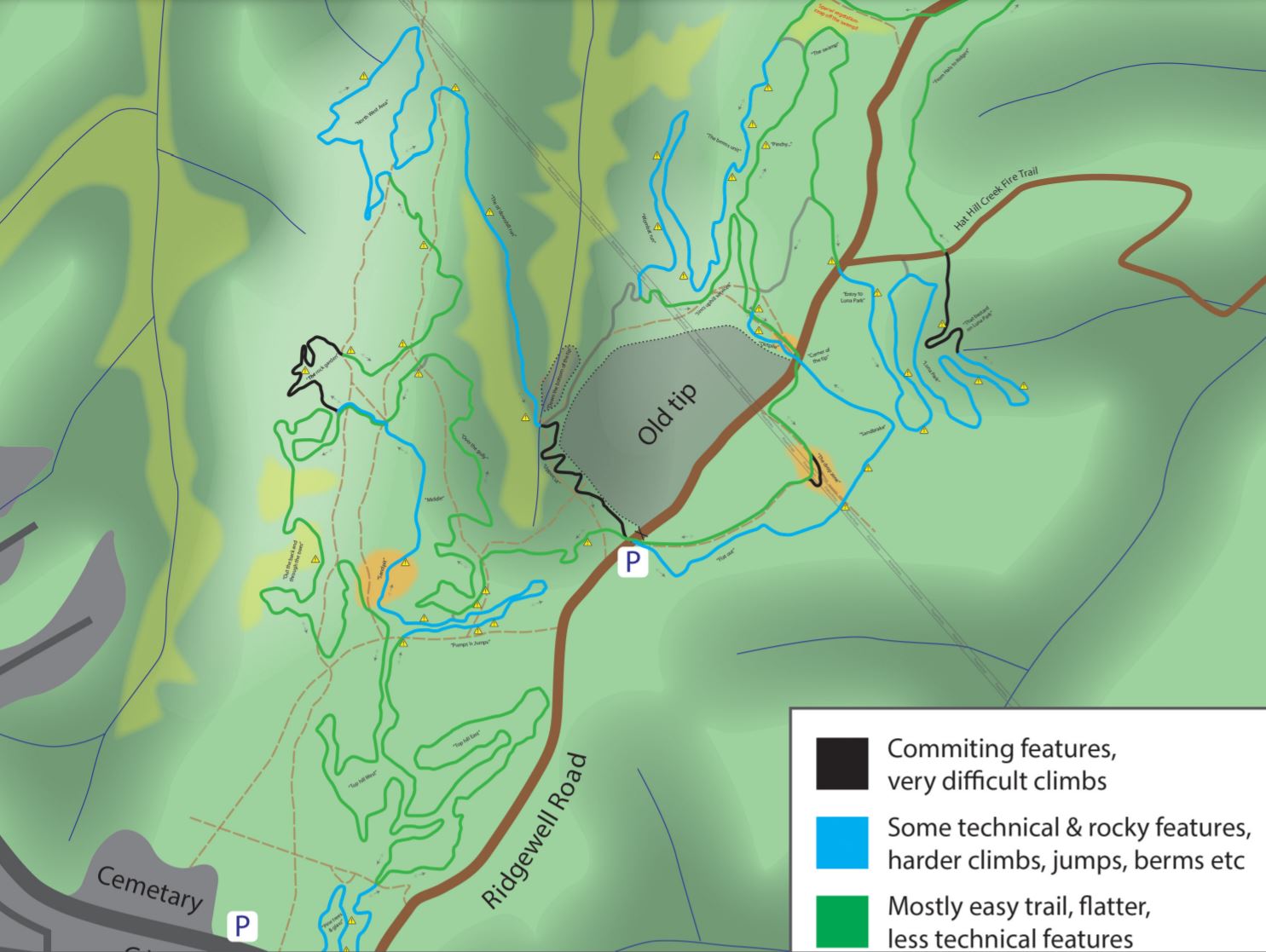

NSW state government anounces $50 million to the conservation of the Gardens of Stone State Forest with the creation of an eco-tourism sight close to Lithgow, including 35km of MTB trails.

RailCorp - rail corridor impass

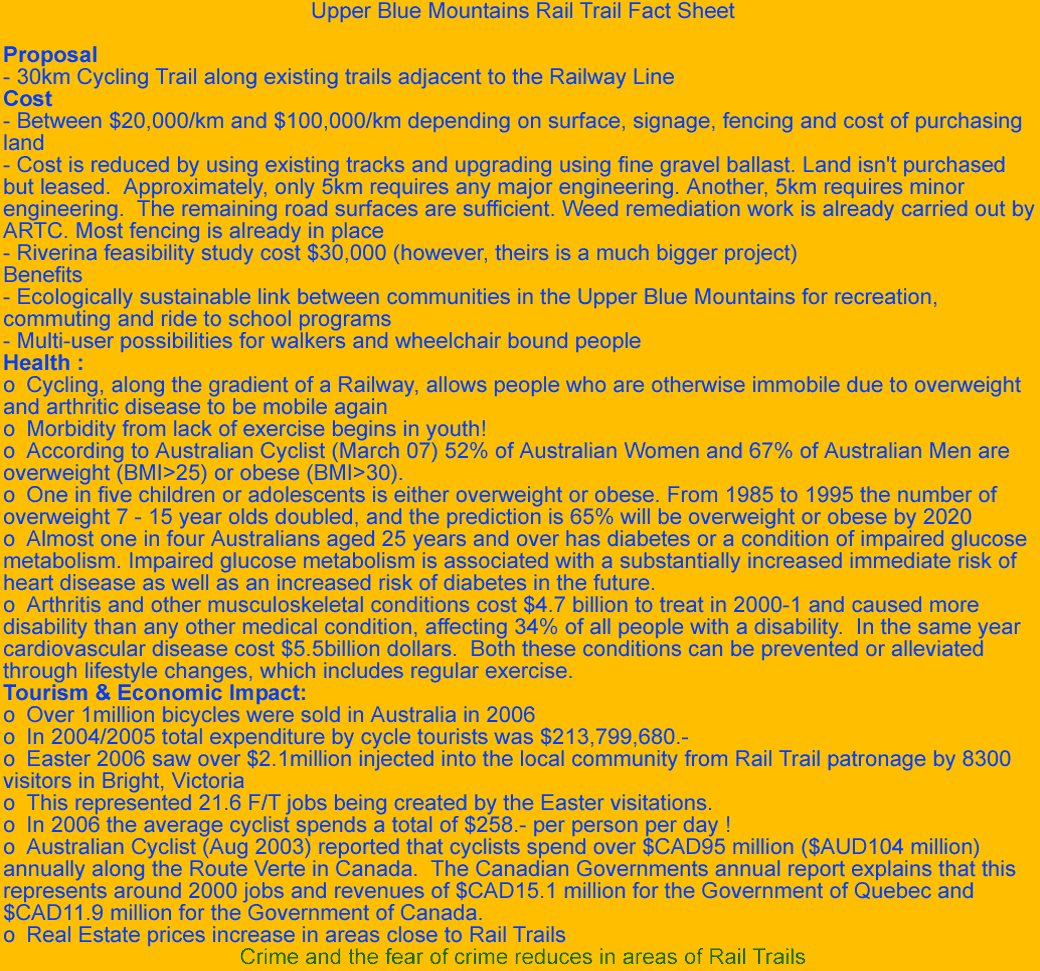

Rationale (health and economics) for the development of the trail

Cycling participation in Australia

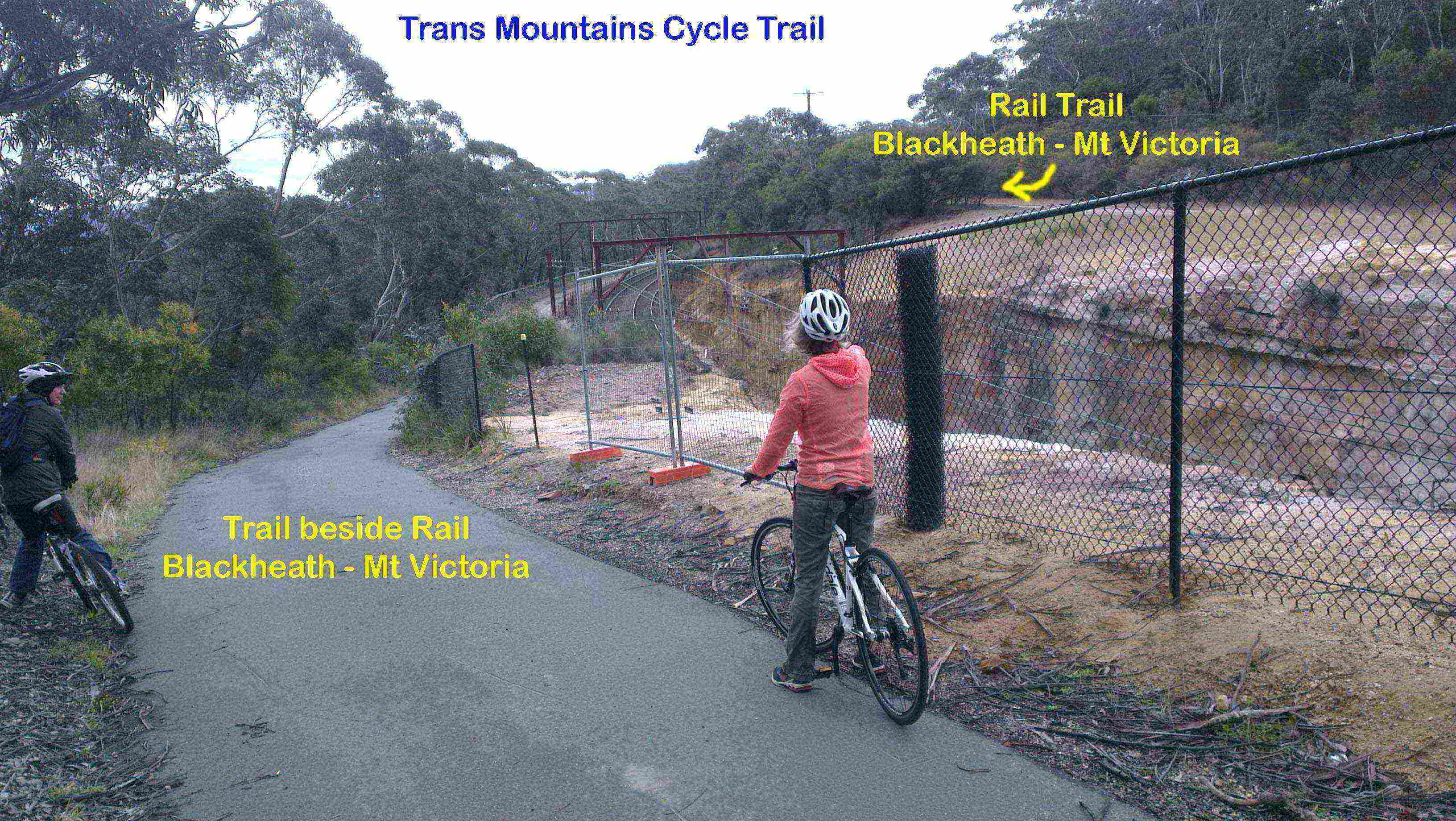

Trails beside Rail or Rail Trail

Blackheath - Mt VictoriaUpper Blue Mountains Rail Trail Lower Blue Mountains Zig Zag Rail TrailHealth

Wollemi National Park

Manly to Mudgee

The concept of linking disparate cycle paths, Rail Trails (Newnes Rail Trail and Kandos-Mudgee Rail Trail) and fire trails to create a 300km cycling odyssey. Most trails already exist. Upgrading and linkage is needed. Thereby, creating a cycle randonneur/pack cycling/cycle touring experience.

Newnes Glow Worm Rail Tunnel (2020)

Carriage ruins of Wolgan Valley Rail Trail (October 2020)

Old cutting (October 2020)

Evidence of previous rail (October 2020)

Old Carriages (October 2020)

Wolgan Valley (October 2020)

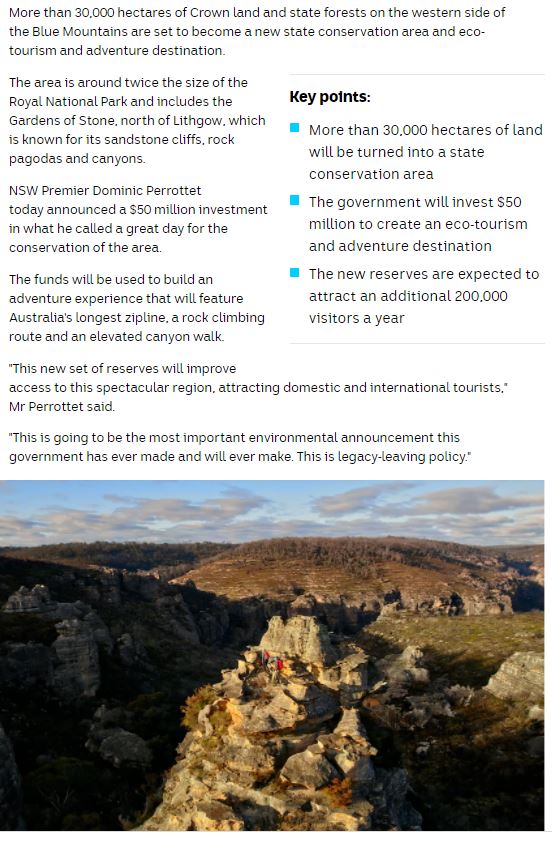

Central West Bike Trail (September 2020) : Manly to Dubbo

Imagine linking the Central West Bike Trail with Sydney????!!!!!!!

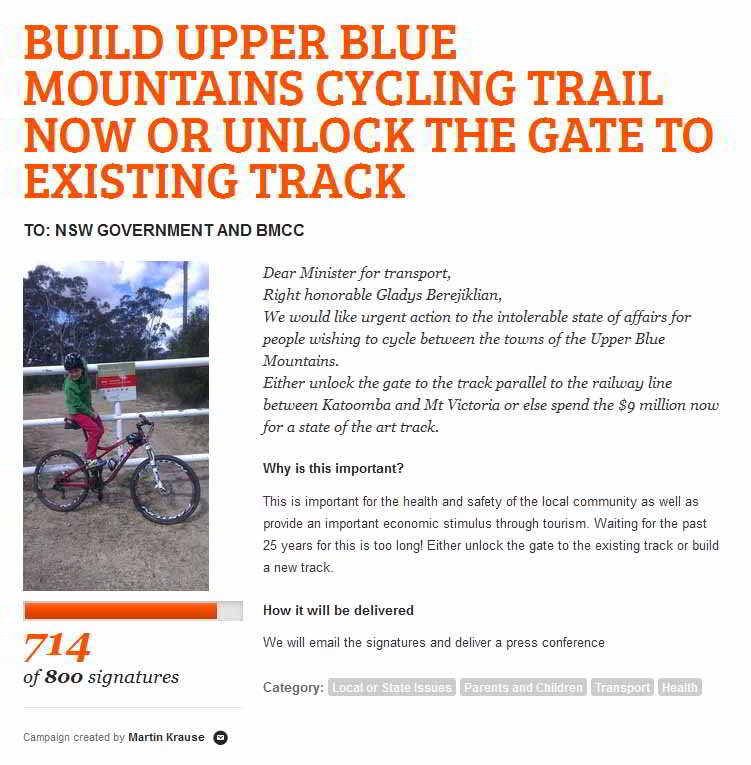

Background

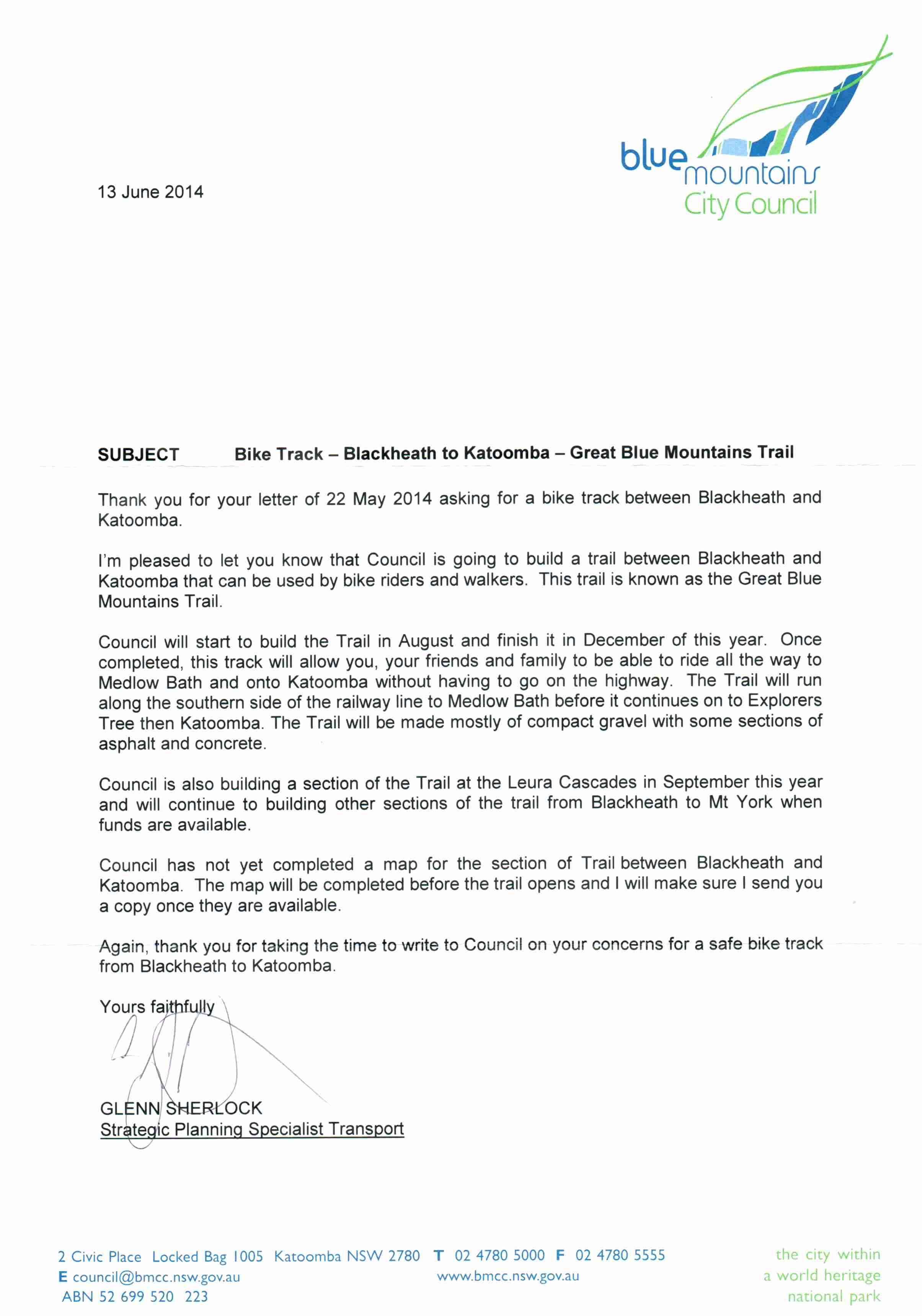

The concept of a Trail following the Rail was brought to the attention of Blue Mountains City Council in 1998 through the presentation of a petition, which included over 1000 signatures. The objective was to open one of several tracks, which follow the railway line, to public use as an off-road biking and hiking trail between Wentworth Falls and Mt Victoria. Several issues arose with this proposal. These issues included Sydney Water Catchment area, several non-integrated and stratified government departments, questions ownership of the land adjacent to the railway line, safety - including the surface of the track, fencing, and gradients, environmental impact, as well as the cost of building as well as maintaining another BMCC asset such as this track.

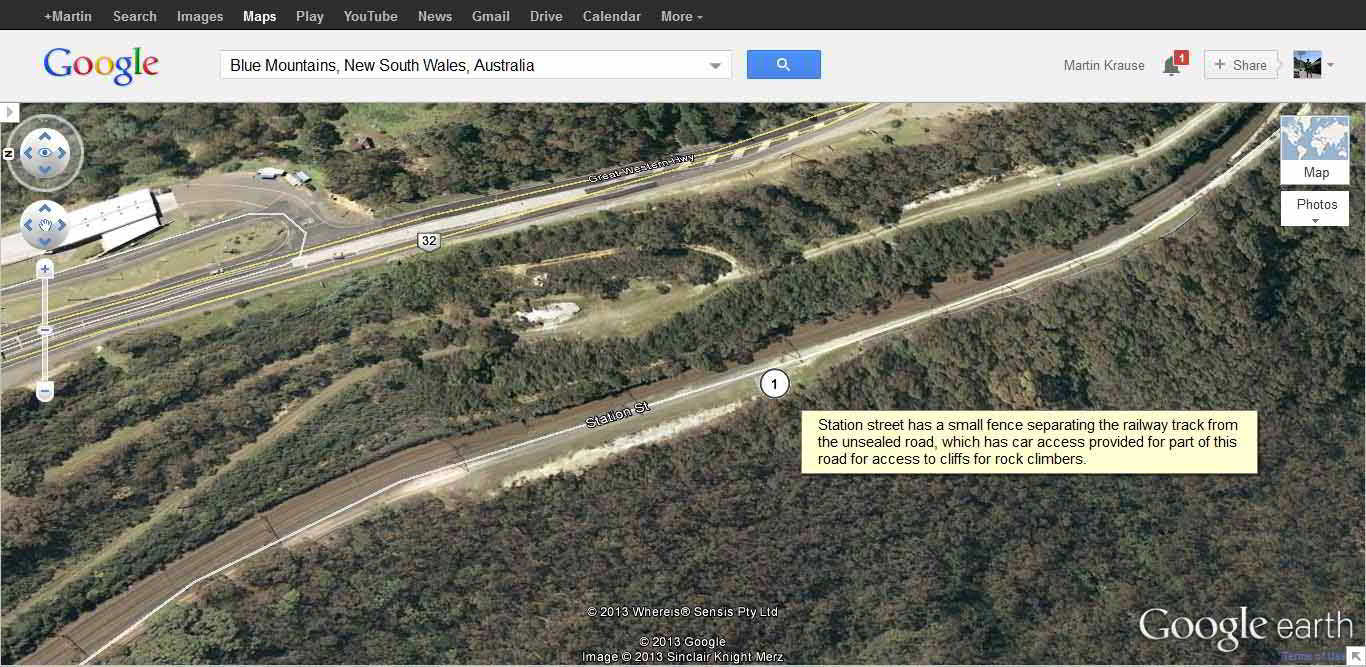

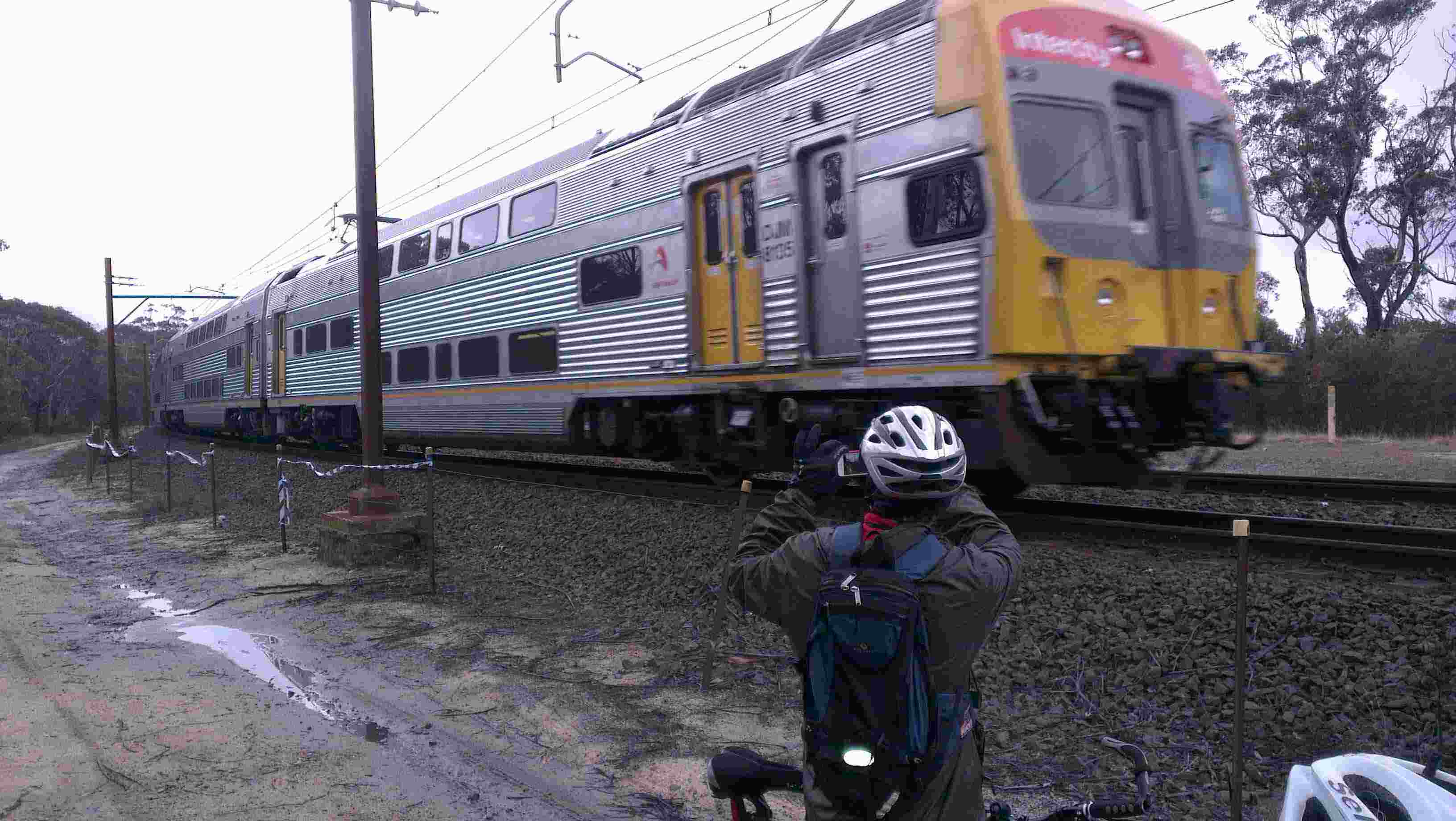

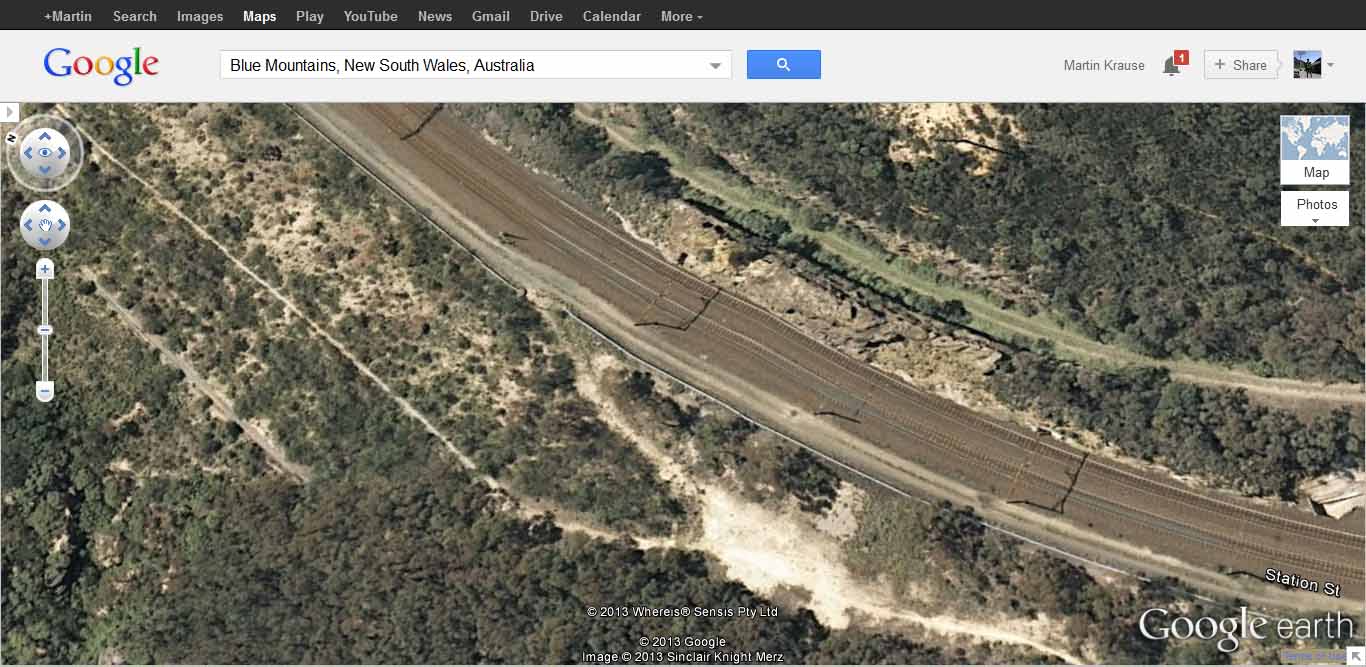

At the time, public access to the track between Medlow Bath and Blackheath already existed. However, the track between Katoomba and Medlow Bath went through Sydney water catchment land, but was still used illegally by commuting mountain bikers. This illegal use was necessary, as the Great Western Highway had extremely large amounts of heavy traffic on a very narrow road. The track to the west of Blackheath essentially followed an existing suburban street until it became railway land. Although car access had been developed and granted to rock climbers, early in the 1990's, by the late 1990's, there was a reluctance to grant similar access to cyclist and worse still a fence was erected half way along this strip to prevent any through traffic, hereby only allowing access from the west for climbers and their cars. A similar situation existed between Leura and Katoomba, where illegal bike commuting access was occurring along the southern side of the railway line. In this instance, this was occurring because the road trip between the 2 towns involve very steep hills, whereas along the railway line the gradient was extremely modest.

A public information campaign was launched through the Blue Mountains Gazette, as well as approaches to BUG's (bicycle user groups) in the Blue Mountains and Bathurst, schools, TAFE, outdoor communities, NPWS, as well as various Chamber of Commerce (esp Wentworth Falls and Lew Hird in particular), Blue Mountains Tourism as well as Blackheath and Mt Victoria community action groups. The former headed by Liz Bastian. Interestingly, both labor, liberal and some independent councillors and politicians mooted for the project. Surprisingly, the people who were least helpful were Bicycle NSW and the Greens!!!!

Correspondence was entered into with NSW state and Federal governments across many departments, including local sitting members, departments of transport, environment, health and tourism. Several meetings were held with many members of staff and people from the local community at BMCC, which were co-ordinated by Glen Sherlock. I personally invested a lot of my time investigating every plausible reason for constructing such a trail, by looking at comparative projects interstate and overseas, as well as investigating the nature of 'trusts' to take 'ownership' and maintain an on-going commitment to the maintenance and development of the asset.

Through continuous lobbying, the NSW labor government conceded the need for safe cycling across the Blue Mountains by agreeing to build wide cycling tracks along the great wester highway during it's upgrading. The completion, in 2012, of the cycling track between Wentworth Falls and Bodington Hill is an example of this, and represents a vital link to the well frequented Andersons and Oaks fire trails between the upper, mid and lower Blue Mountains towns of Wentworth Falls, Woodford and Glenbrook respectively.

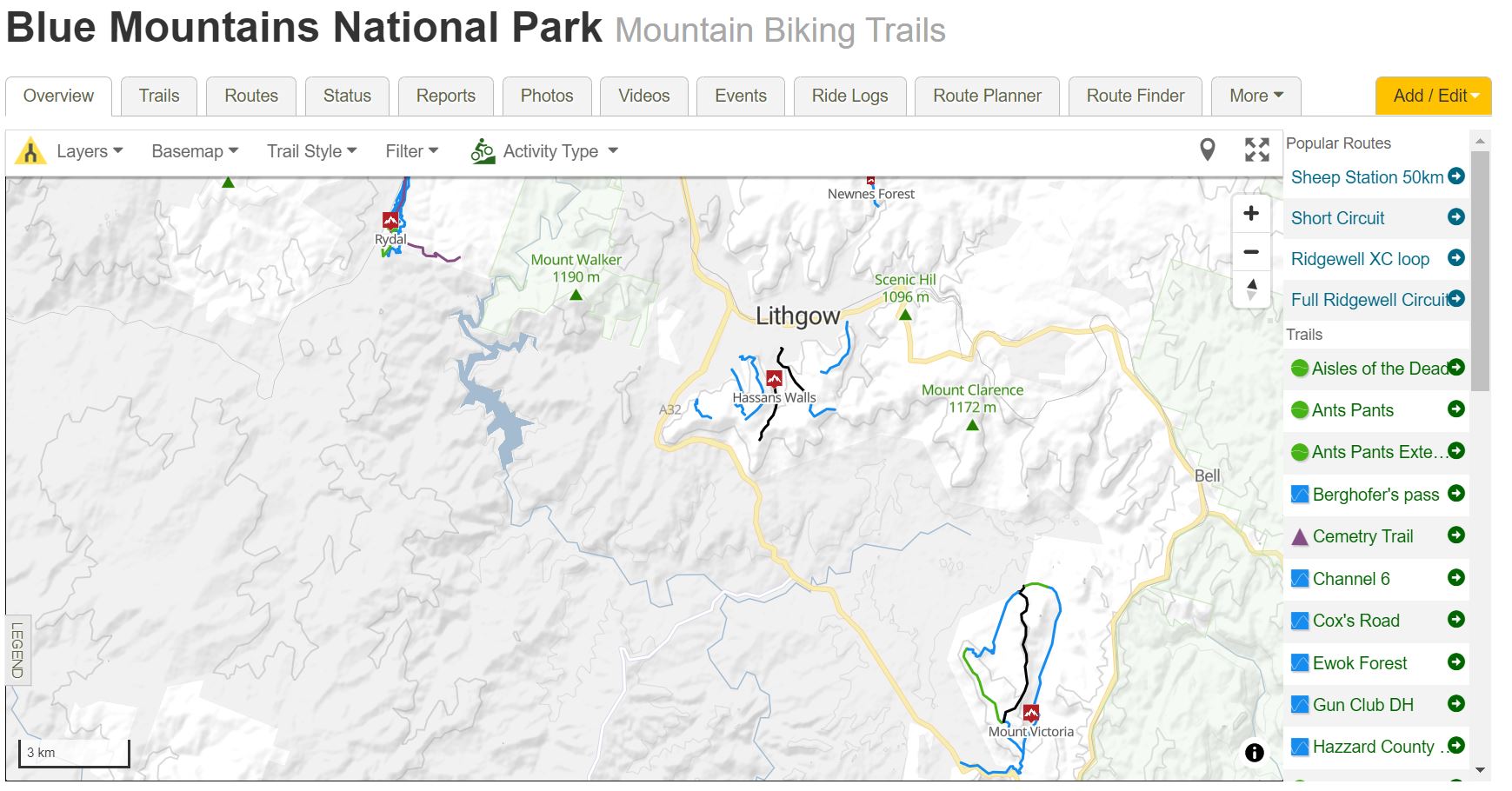

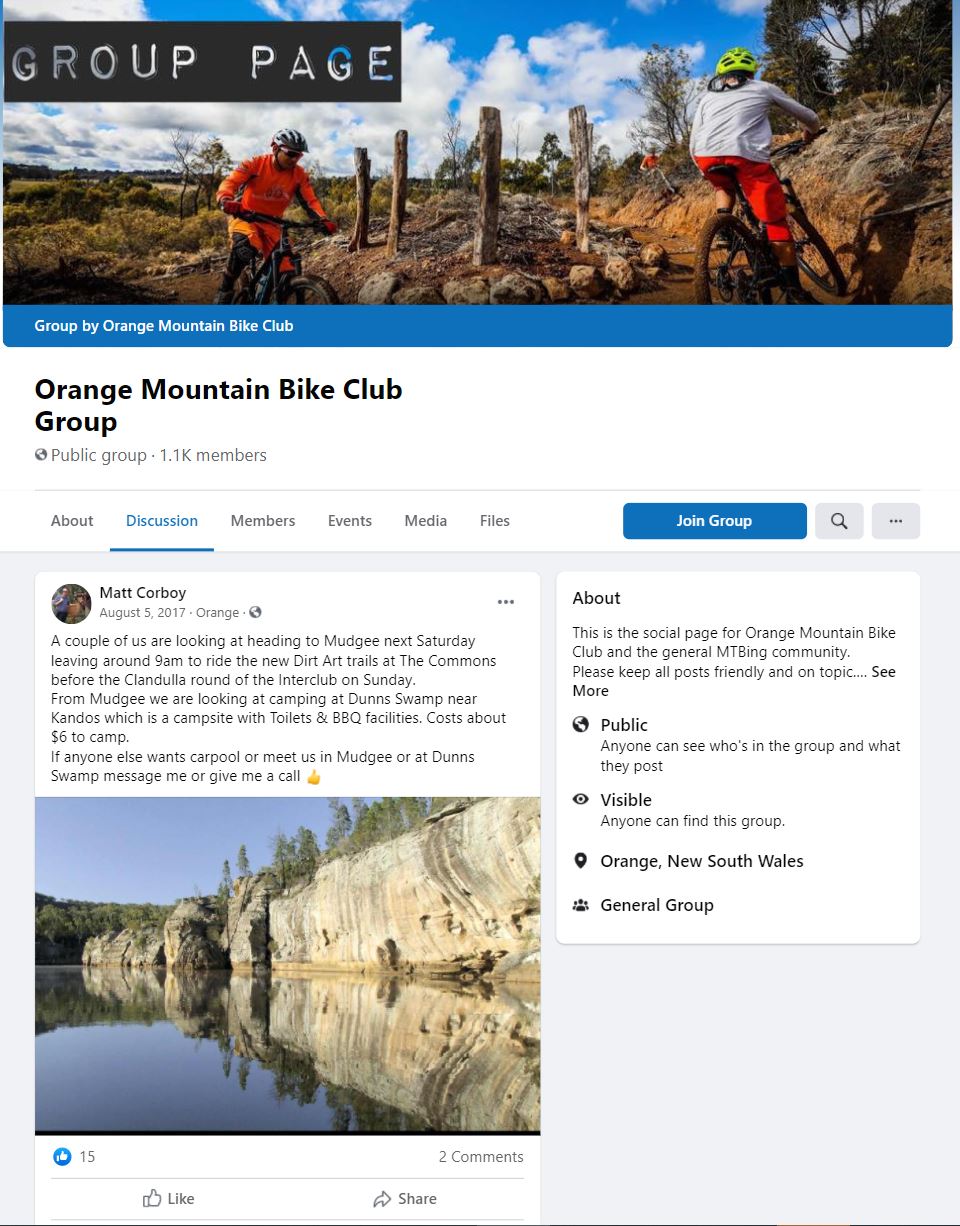

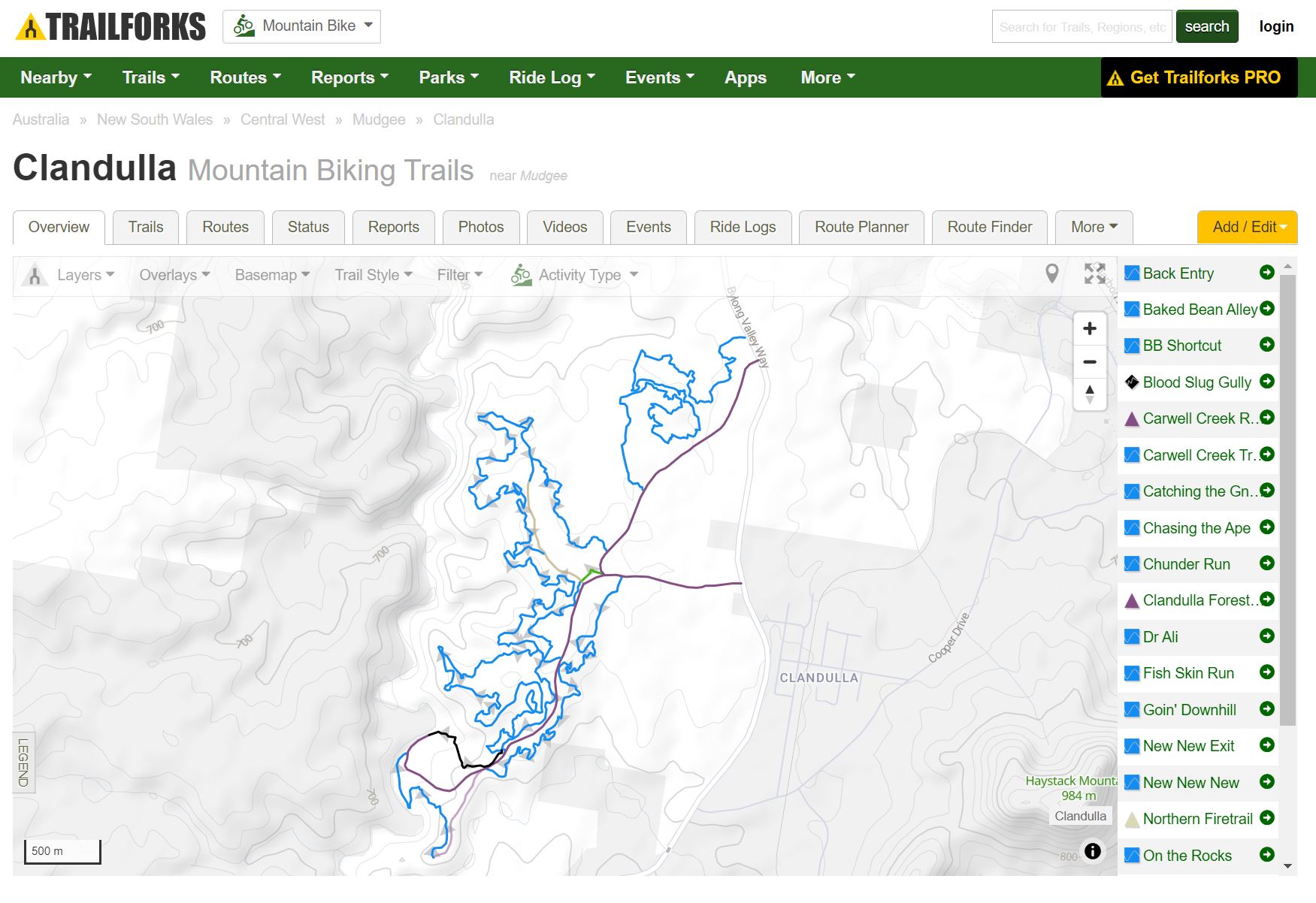

Additional considerations were, that this cycle path created an important 'backbone' to accessing cycling facilities either side of the trail, with cross country mtb'ing trails at Katoomba, Blackheath, Mt Victoria and road cycling into the Megalong Valley. Additionally, it formed an essential part of the Manly to Mudgee and the Dubbo pack cycling trail, which again had cycling facilities either side of it, These places included Hassans Walls Gravity Trails in Lithgow, Rydal cross country trails near Lthgow, Wolgan Valley and Newnes Plateau, Oberon, Clandulla near Kandos, Dunns Swanp and Rylstone. Finally, the central west pack cycling route from Mudgee to Dubbo return circuit became a great sensation for family and friends cycle toruing during the COVID-19 crisis of 2020-21.

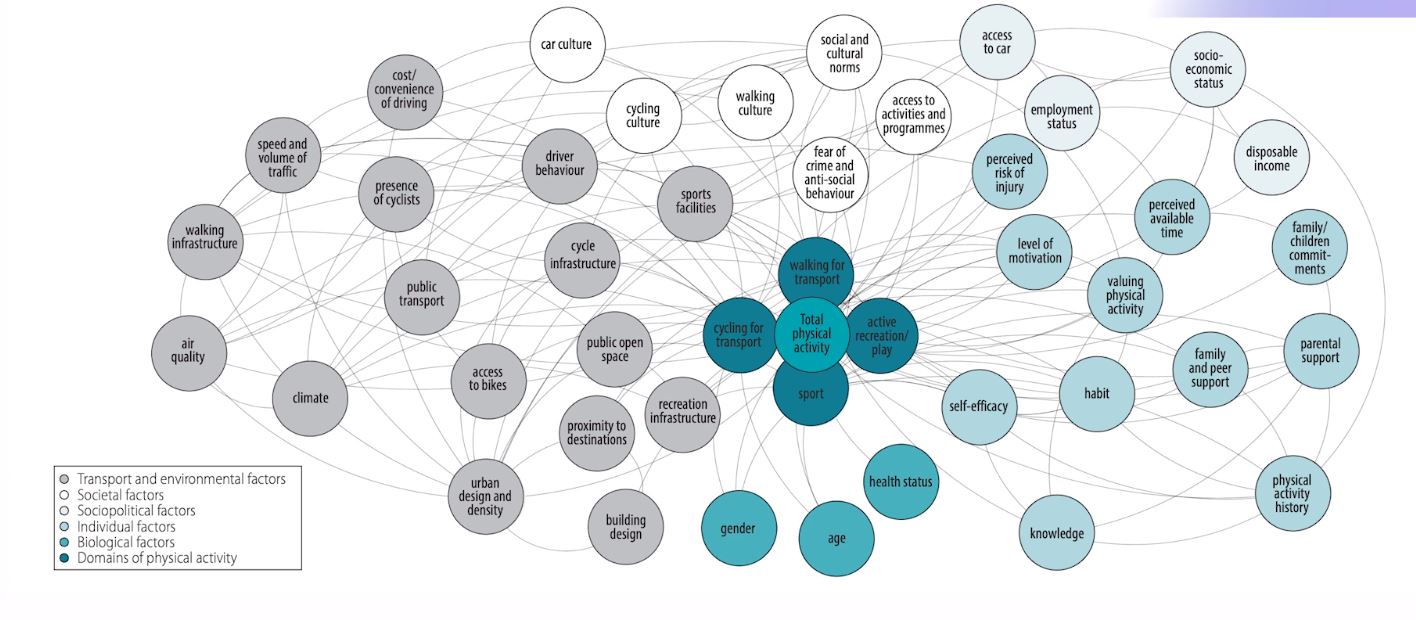

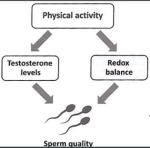

Active transport for personal health and the health of the environment - systems map of factors contributing to uptake (Rutter H et al 2019 Bull World Health Organ)

Backdrop : 2011

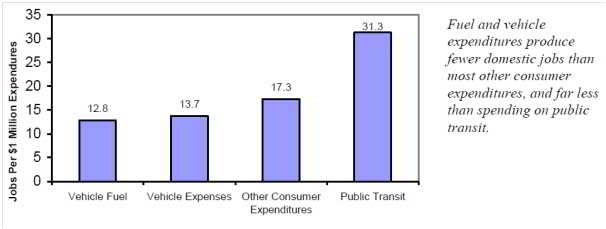

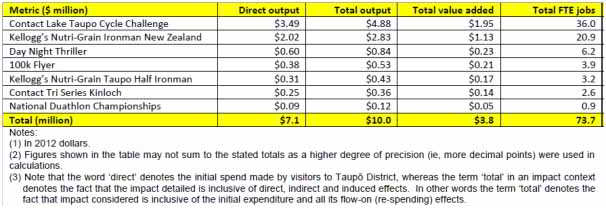

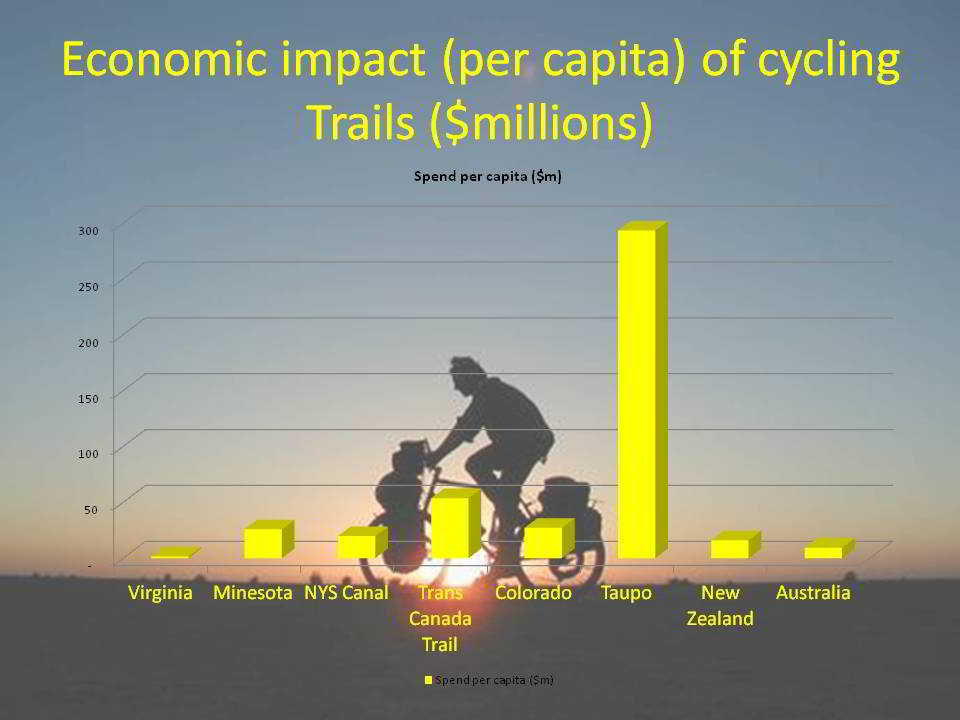

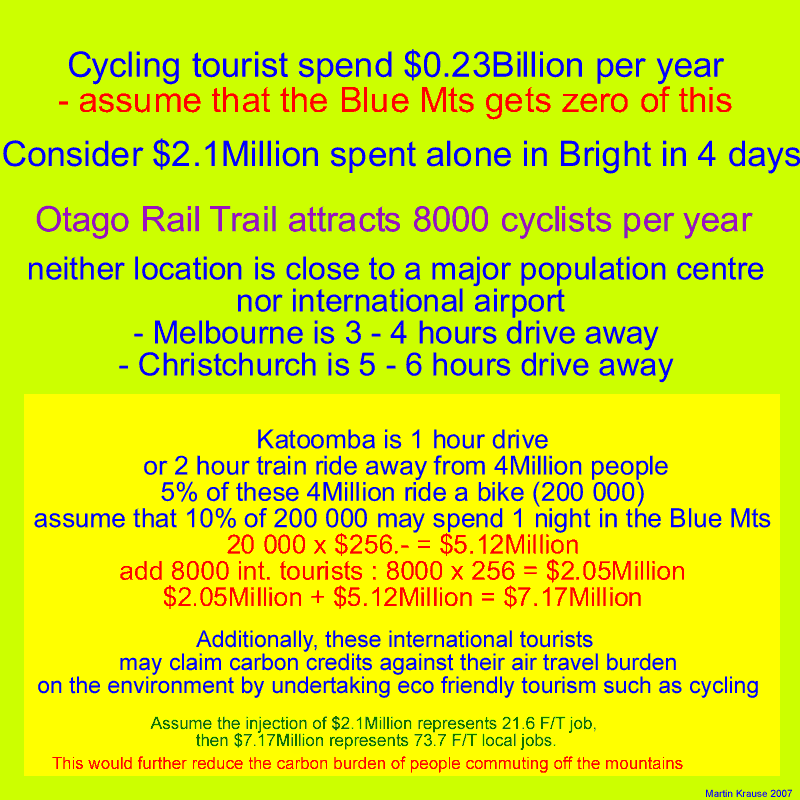

Cycle Tourism: Events and tourist trails generate $254 million a year in Australia

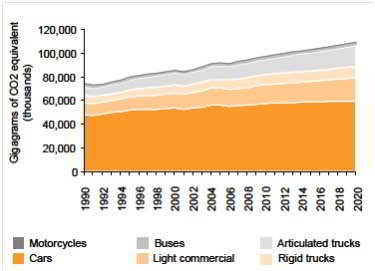

- $9.6 Billion : Car trips cost 5.9¢ a km in CO2, air, water and noise pollution. In 2010 we drove cars more than 163 million km

- Regular bicycle riders take one less sick day than non-riders, saving businesses $61.9 million a year

- The Australian bicycle industry employs 10,000 people and generates $139 million income tax revenue.

- Inactivity costs Australia $13.8 billion a year. Everyday cycling can provide recommended activity levels and reduce this cost.

- Bike and accessories are worth $1 billion a year, generating $100 million gst revenue

- 4 Million people: 18% of Australians cycle in a typical week, 1.6 million use their bikes for transport

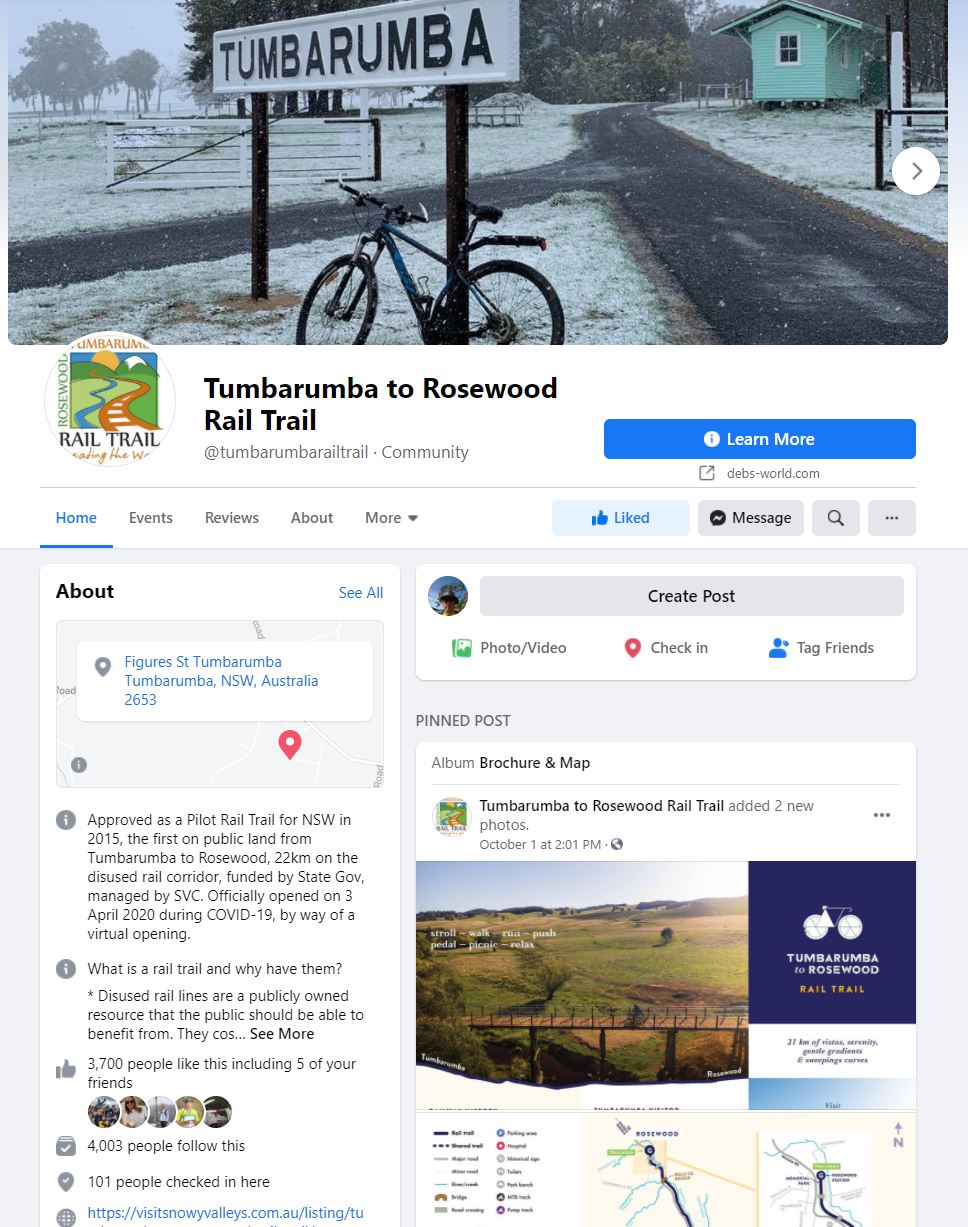

Economic Impact - Real Estate : Derby Tasmania : September 2021 National News - ABC

Many investigations into Rail Trails in North America eluded to the beneficial impacts of RT's on the liveability, connectedness, and quality of life that a RT brings to a health minded recreationally oriented community. Additionally, disused rail corridors and abandoned towns suddenly get a new lease of life. Even crime reduces in these regions. These factors all have a positive impact on real estate prices in a community serviced by cycling infrastructure.

In September 2021, a dilapidated 2 bedroom 100 year old shack sold, in Derby, Tasmania for a record $1.3 million. 10 years previously it had sold for $160 000. The real estate agent was quoted as saying "I've never had so many calls about a property before … I would have easily had hundreds of calls and texts and emails."

What happened???? World class, cross country, enduro and epic mountain biking trails. A government investment of $4 million turned a virtual 'ghost town' into a must do, go to, international and domestic mountain biking destination!!!

"One hundred years ago people were coming back from World War I, new businesses were opening here, mining was heating up again, and now here we are 100 years later and it's mountain biking, not tin.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-31/derby-crack-house-sells-for-1-3-million/100419092

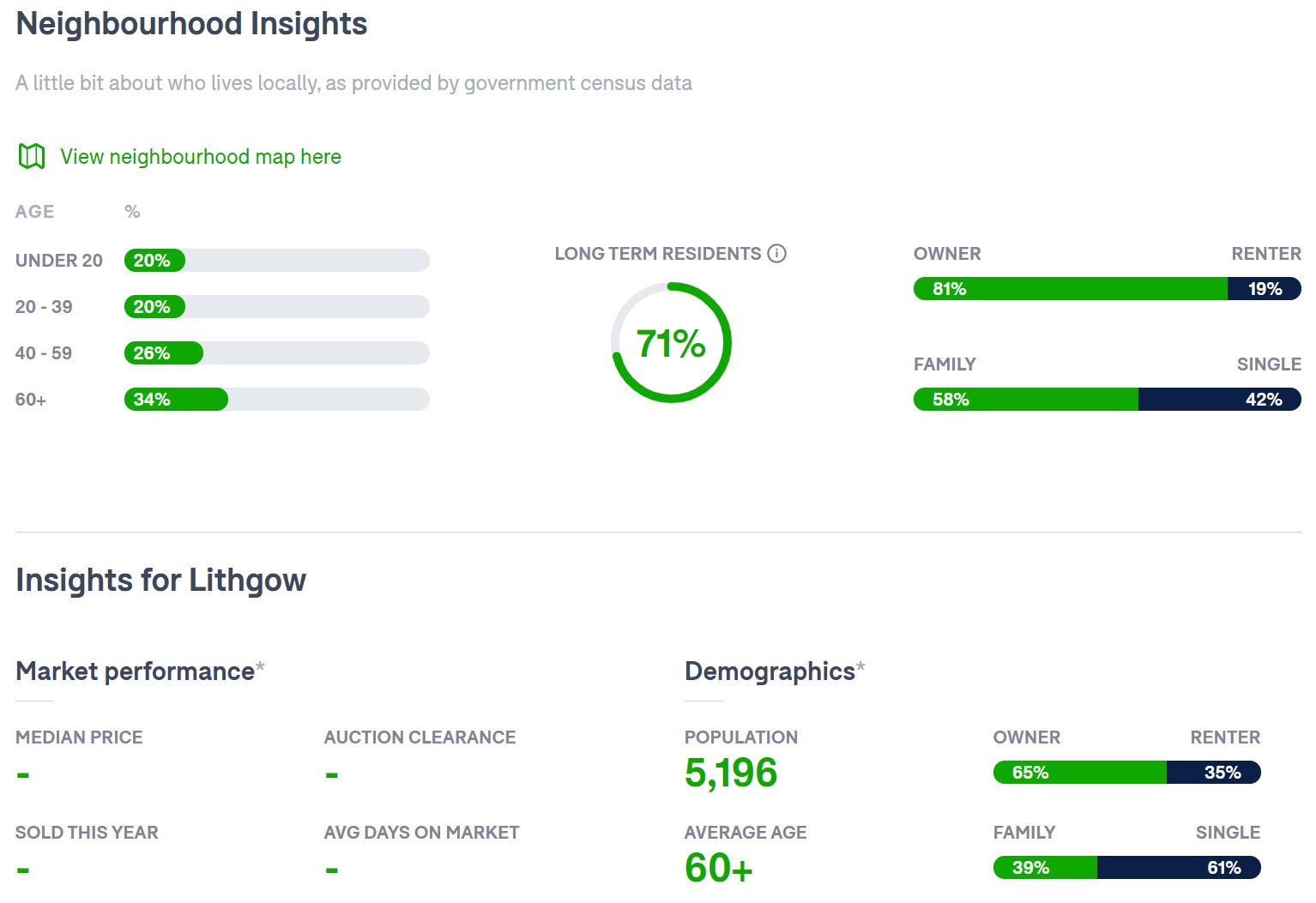

The following are Lithgow neighbourhood insights from Domain real estate in September 2021.

This could be Lithgow : a community transformed from coal mining and a jail to a progressive mountain biking destination with all the economic windfalls which go with them. Improved liveability and quality of life through the economic boost from cycle tourist spending creates a mosaic of recreational activities as well job opportunities.

Rocky Trail has held Downhill races at the Pony Express, endorsed by the local MTB club, for about 10 years until 2016/2017. It has been difficult for the club to maintain the trails as the downhill market is in decline – this is why we propose the Superflow-style of trails in this project as they will attract a broad range of mountain bikers not just to events, but also for ongoing visitation.

Rocky Trail’s ultra-endurance event, the Jetblack 24 Hour has had its home in Lidsdale State Forest in Rydal since 2017. Attracting Australia’s top endurance and marathon racers, it has become a hugely popular event with the casual mountain bike riders and racers thanks to the uniquely comfortable set up of the event village, which we have been able to achieve in Rydal.

The 2019 edition of the JetBlack 24 Hour with its JetBlack 6+6 Hour offspring took place at Rydal Showgrounds near Lithgow on 23+24 March 2019. More than 300 race competitors from all over NSW and the ACT raced in teams of up to 6 in the 24 Hour competition and up to 4 in the 6+6 Hour event, clocking in almost 2,900 laps and recording more than 27,500 racing kilometers over the weekend.

The Jetblack 24 Hour once again transformed the Rydal Showgrounds in Lithgow into a vivid mountain bike event centre and tent village over the weekend with 435 racers and overnight event visitors plus an est. 50 local spectators, injecting more than $250,000 into the local economy.

Entering its second decade the 11th edition proved that the 24-hour racing concept is more and more becoming a social affair: more than a third of all racers competed in the teams of six-classification – and whilst everyone from solo to team participant races hard and gives into this unique endurance challenge, it’s all about that fun weekend away with fellow mountain bikers, family and friends - and this aspect is what we will put a strong emphasis on for the future promotion and growth of this event.

https://www.councilnews.com.au/2021/03/15128116-draft-hassans-walls-mountain-bike-trails-strategy

Lithgow could be one of the hubs of the Manly to Mudgee and Dubbo bike packing trail as well as an ultimate destination for downhill mtb'ing. Similar to how Tasmania was, Lithgow struggles as a tourist destination. Tasmania used to have tourists who came to see convict ruins, which is probably similar to a country as beautiful as Poland marketing itself as a 'concentration camp' destination - 'welcome to the gates of hell', Now, rather than the horrors of Port Arthur, it's a wine, food, cultural and sporting outdoor destination. Tasmania markets itself as such and now has a high influx not only of tourists but also of people relocating for it's liveability. Lithgow with it's geographic proximity to Sydney and the iconic World Heritage Blue Mountains, as well as the gateway to the west, can become an even better place to live.

Derby, in Tasmania, is an example of how mountain biking can kick-start an economy. “A ghost town of just 173 people just three years ago, Derby is now a renowned MTB hotspot that generates $23 million a year.”

https://www.mtba.org.au/wp-content/uploads/CCJ17427-Blue-Derby-Case-Study.pdf

There are currently about 90 km of trails in the Blue Derby network. It is not necessary to build such a large network of trails to gain significant economic benefit. Small mountain bike projects can attract similar visitor numbers to large-scale projects.

Smithfield Mountain Bike Park in Queensland is only 16 km from Cairns. It has approximately 25km of trail and sees 33,600 users per annum.

Forrest in Victoria, a 1.5-hour drive from Melbourne has 65km of trail and sees usage volumes of between 22,000 – 25,000 per annum

The Wild Mersey project in Tasmania is a great example. Due to its proximity to population centres, the 16km section of stacked loops in the Warrawee Reserve has seen usage volumes similar to that of Blue Derby, with 25,000-30,000 users annually.

Other examples of gravity trails include Maydena, about an hours drive from Hobart, Tasmania and Whistler, Canada, which makes more money from cycling than it does from winter sports.

The seminal MBTA 2007 study Whistler Report is the one most commonly used as a baseline. Surprisingly it showed that over half (52%) of Whistler visitors weren't there for the bike park but for the Whistler valley's exceptional trail system. Bike park ridership was greater though due to number of repeat visitors (76,600 bikepark vs 25,000 trail for the mid June to mid Sept study period). There was less than 10% crossover between bikepark and valley trail riders showing that the trail system, in and of itself was a significant draw. A large majority (70% were male). Another large majority (68%) were non-locals. Riders in Whistler (including bikepark and trails) were predominantly in the 30-39 category (37%) with bikepark riders being generally older than trail riders. Visiting riders were strongly represented by 18 and under year olds (18%) which brings down the average age making visiting riders in Whistler relatively younger than for any other area with an EIA (except for Moab where the average age of visitors was also younger). Living in Whistler I would hazard a guess that there is a noticeable subset of younger travellers who are more budget-conscious that travel to this core name-brand destination but the younger demographics' average dollar spend isn't significant.

As to spending, 90% of visitors were overnight visitors. Both bikepark and trail riders stayed a fairly long time (4.5 to 5 nights). Bikepark riders spent more per day ($133) vs trail riders ($94) - but taking out the price of the bikepark passes, trail riders spent more. International/oversea visitors spent the most, stayed the longest (7 nights) but spent less per day on average; probably because lodging costs drop as you stay longer. Income of riders was all over the place with the bell curves having fat tails at bottom and top end (ie fair amount of budget mixed in with bling but with lower incomes predominantly among trail riders). https://www.pinkbike.com/news/economic-impacts-of-mountain-biking-tourism-2014.html

A 2014 Squamish (just down the road from Whistler and up the road from Vancouver) study found that 75% of trail users were visitors (a large increase); jumping to 85% on the Half Nelson landmark trail. The factor dropped considerably over the past 7 years with male percentage dropping to 55% showing that Squamish trails drew increasing female ridership. The study counted 1339 riders over a three day weekend. A conservative projection estimated rider counts at 1920 visitors/week; 640 locals/week. It was then projected that 25,000 riders visited Squamish on just weekends over the riding season (26 weekends) roughly doubling that number when including weekdays. 40% stayed overnight spending $ 215 per person per trip or approx $80/day (average stay was 2.5 days). Day visitors spent $ 37 per day.

Economic benefits of mountain biking for 'tiny towns' are further detailed in https://adventure.com/mtb-mountain-biking-saving-tiny-towns/. Although Lithgow isn't a tiny town, the potential economic impact is never-the-less clear.

Hassans Walls lookout, Lithgow, Australia

The effect : 1998-2003

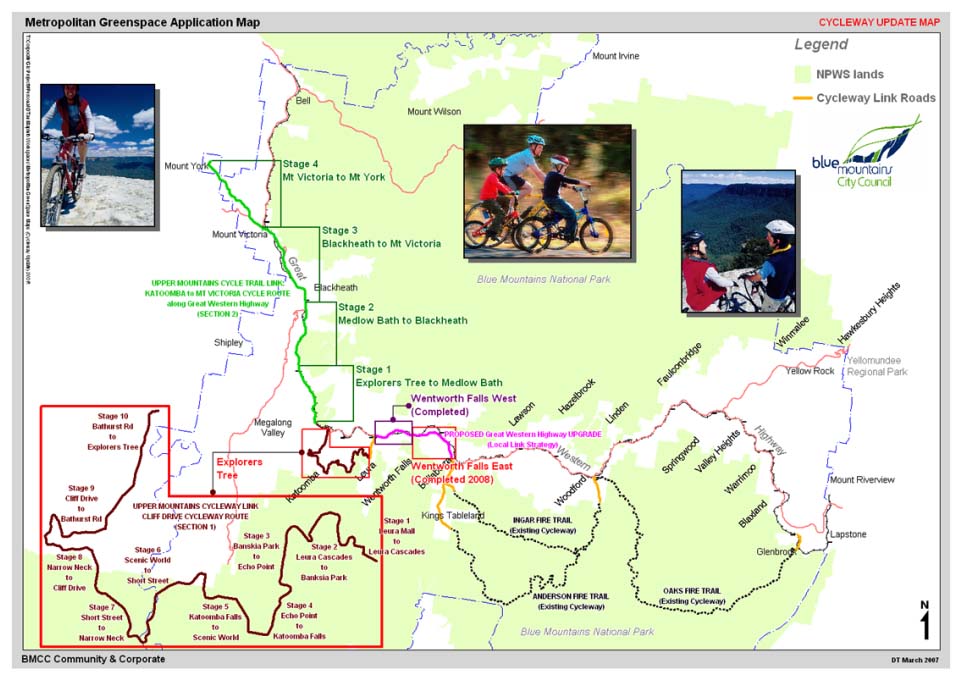

BMCC received funding from the State Government , Dept Planning as part of the Greenspace Program to undertake the feasibility study which was completed in 2010. They again applied for funding from the same program in 2011 to undertake a Review of Environmental Factors (REF) for the trail which was completed in March 2012 and a Signage and facilities Plan was due for completion in June 2012. Both the REF and Signage Plan were requirements from the Dept Planning.

It was the intent of BMCC that during the next round of grants in September 2012 from the Greenspace Program that they apply for funds to begin construction.

BMCC also made application to the various State/Federal stimulus fund rounds without success until 2013.

After 15 years of campaigning, in 2013, Federal Labor Government make a funding announcement to develop the trail as far as Lithgow.

The Federal Labor Government today announced it would contribute $500,000 towards the construction of a new walking and cycling track in the Blue Mountains.

This funding is for the second section of the Great Blue Mountains Trail which will add 13.2 kilometres of new walking and cycling track linking the towns of Katoomba, Medlow Bath & Blackheath.

Minister for Regional Development and Local Government, Anthony Albanese said the trail would add to region's appeal as a walking and cycling destination.

"Tourism is the primary economic driver in the Blue Mountains region and the trail will provide a new and interesting visitor experience and bring a positive economic impact," he said.

"The new trail will generate tourism spending by New South Wales, interstate and overseas visitors and support local businesses associated directly with trail activities such as tours, cycle sales and hire, as well as for cafes and hotels."

Senator for New South Wales Doug Cameron said the newly funded section will be moderately graded and offer the local community and visitors a safe connection through scenic areas.

"The trail will eventually go for 36 kilometres from Leura to Mt York, and to the lower mountains and Lithgow. Its moderate gradient will make it accessible and available to walkers and cyclists of all ages, including families," he said.

"This project is a good example of the real benefits of targeted, long term investment in regional communities.

"The construction of this project, and the resulting increase in tourist numbers, are expected to create an additional 250 jobs in the region."

Funding is being provided to the Blue Mountains City Council under Round Four of the Australian Government's Regional Development Australia Fund.

Stage 2 of project will be completed in the second half of next year with the total 36 kilometre regional trail to be completed by June 2019.

Tuesday, 11 June 2013

Media contacts:

Minister Albanese: Virginia Kim 0407 415 484

Senator Cameron: Mark Andrews 0417 024 890

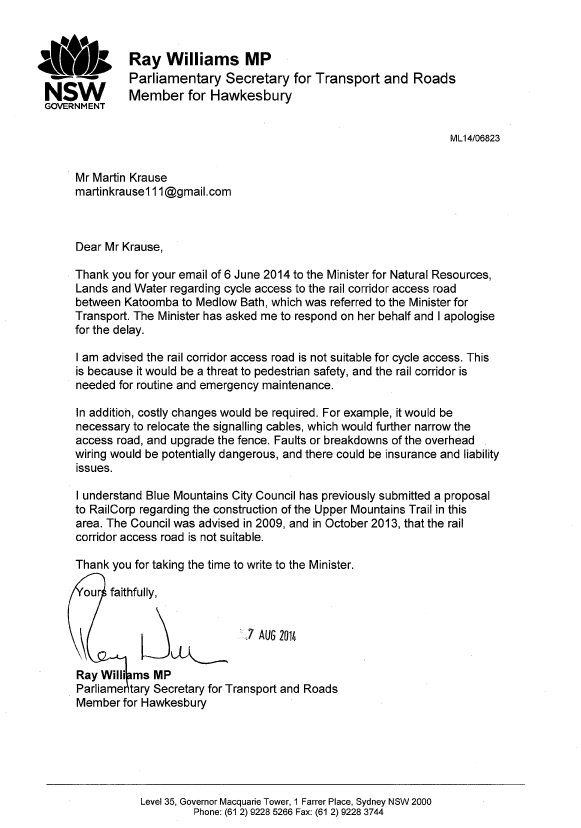

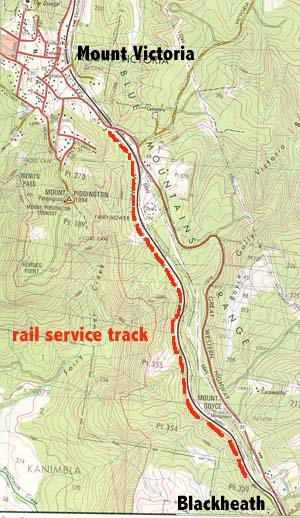

Rail Corp Minsitry for transport Roadblock August 2014

The following letter at least acknowledges a response. Strangely, it is a response from the Ministry of Transport from an email I sent to Sydney Water enquiring about the status of the track on their land between Katoomba and Medlow Bath. Fortunately, BMCC are about to construct their track on the opposite side of the highway to that of the Katoomba catchment. However, we still need cycling access to the Rail Corridor between Blackheath and Mt Victoria. Hence, the response demonstrated very little understanding of the needs of the community, nor the actual technical issues. Firstly, 2/3 of the track between Blackheath and Mt Victoria is already accessable and has been for at least 2 decades and hasn't resulted in any electrocutions, pedestrians being run over, or insurance and liability issues. The remaining closed off 1/3 is no different to the currently open 2/3. Same flimsy fence. No doubt, these issues which they have raised could be solved if there were a willingness to do so.

November 2015 : Rail Corp rejects BMCC's revised proposal.

BMCC and Rail Corp surveyed the Blackheath to Mt Victoria Trail beside Rail and to a lesser extent the Rail Trail. Rail Corp concluded that too many 'pinch points' existed which prohibited the co-existence of cycling and rail maintenance. This is very disappointing as the Rail Trail seems like a great option where the public is clearly being short changed from the prohibition of the use of such a beautiful public resources. BMCC made further submissions for funding for a trail beside the northern and eastern side of the GWH.

Rationale for the construction of a sealed Upper Mountains Trail

1. Introduction

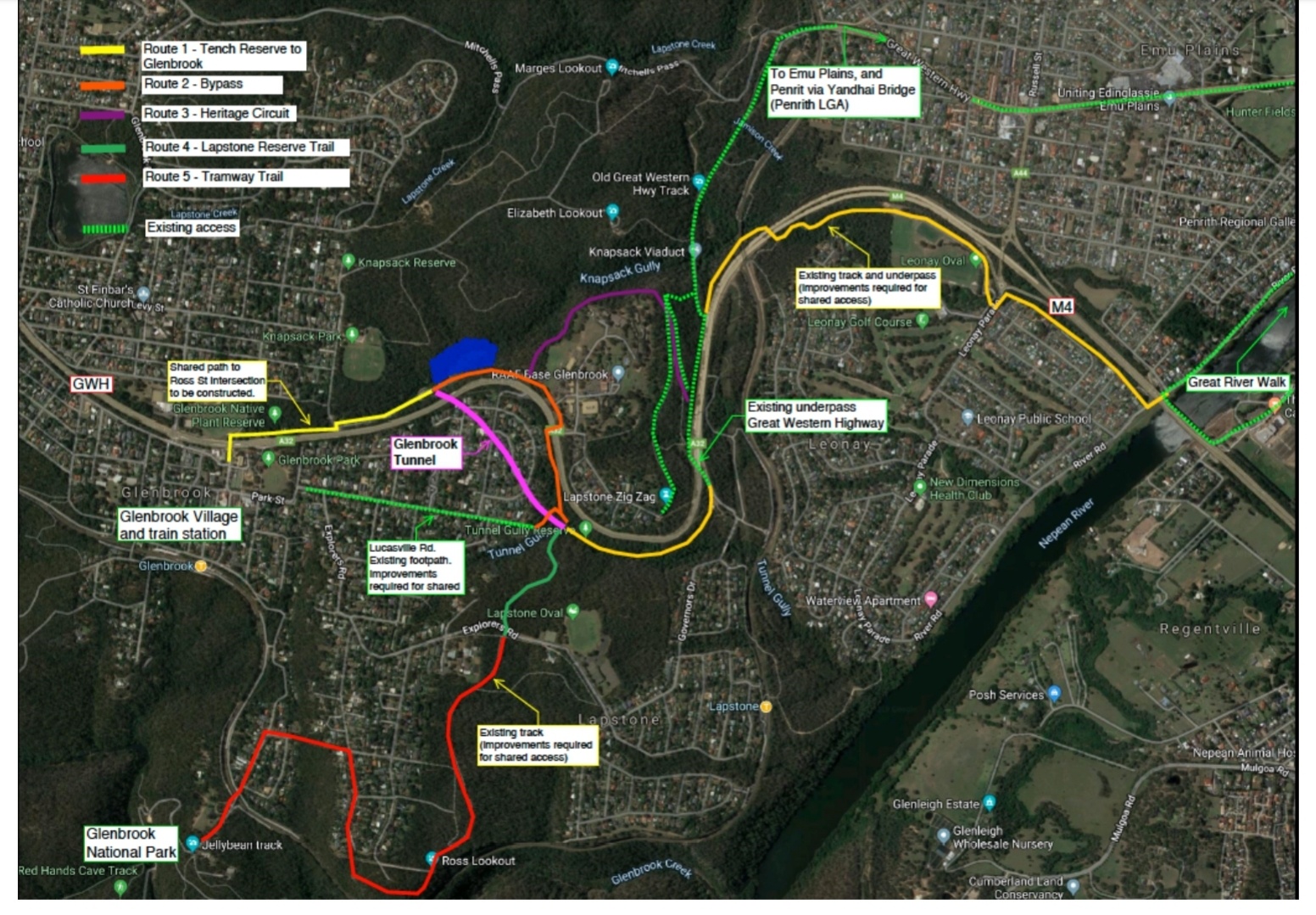

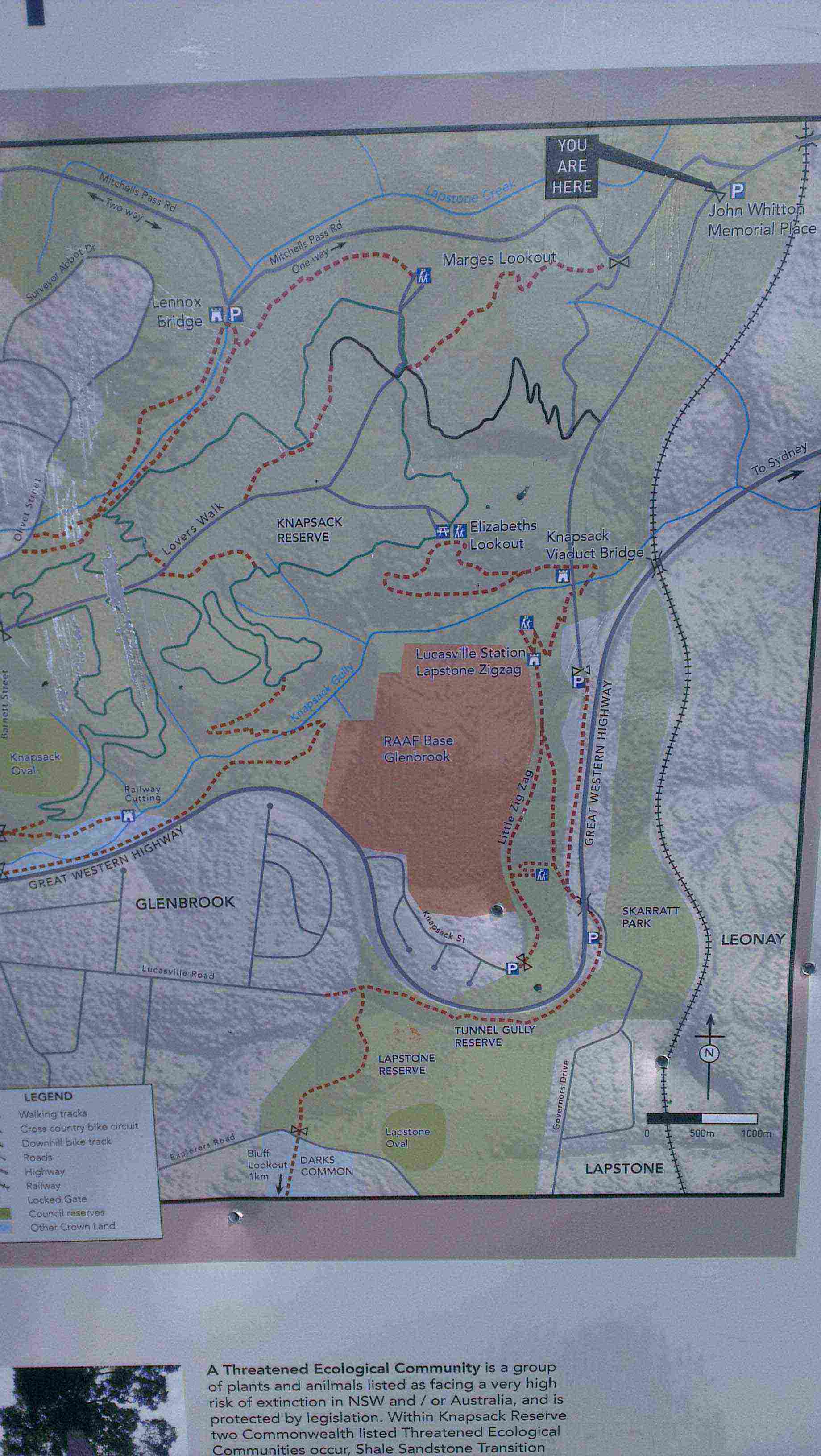

The Great Blue Mountains Cycle Trail (GBMCT) is a visionary trail whereby cyclists and walkers can cross the Blue Mountains from the Sydney Basin in the East to the rural countryside west of the Great Dividing Range, traversing World Heritage listed terrain, Wollemi wilderness and eventually arriving in rural NSW. Currently, sections of this trail exist. There is a partial Rail Trail (the lower mountains Zig Zag) coming up from Emu Plains/Mitchels Pass and traversing Lapstone before making it's way into Glenbrook. Despite, the tunnel in Glenbrook being closed to cyclists and the cuttings becoming overgrown there is potential here for creating a very exciting gateway for the Great Blue Mountains Trail, with very little remediation. From Glenbrook there is the Oaks fire trail which connects with Woodford and after that, the Anderson's fire trail which links Wentworth Falls.

Unfortunately, it is from Wentworth Falls, where the problems with a discontinuous trail begin. Blue Mountains City Council (BMCC) have approved the bike plan for a segregated cycle track parallel to the Great Western Highway (GWH). In fact, they recently received funding which has allowed them to do remediation work on the track between Medlow Bath. BMCC will commence construction of the Katoomba to Medlow Bath section in September 2014 which should be completed in early 2015. Ironically, the section (Blackheath – Mt Victoria) of the rail corridor, where a track which has been open for use by climbers since the 1990's, is the most problematic, in terms of bureaucratic wrangling over cycling access to this area. If these few kilometres of rail corridor can be opened for cycling and walking, then a Trans Mountains Trail becomes reality.

The following is a case which argues for the upgrade of the construction of the Upper Blue Mountains Trail (GBMCTUM) being done by BMCC, the building of the section of trail between Blackheath and Mt Victoria along the rail corridor. These arguments are based on economic, environmental, health and safety issues using current data and comparative case presentations. Ultimately, the amelioration of the dangerous cycling conditions, in the Upper Blue Mountains, through a segregated cycling and walking trail, should make this an iconic cycle commuting, touring and rambling trail linking Sydney with NSW rural country towns like Bathurst and Mudgee.

2. Cycling participation in Australia

As a recreational pursuit, the results of the 2008 'Exercise, Recreation and Sport Survey' show that 1.93 million people cycled in 2008, representing a 21% increase in cycling participation since 2005 and a 34% increase since 2001 (DHAASC 2008). Cycling is now the 4th most popular physical activity behind walking, aerobics and swimming (DHAASC 2008). In terms of ownership, half of Australian households now own one or more bicycles, with the ACT as the state with the highest ownership at over 65% (ABS 2009). For the tenth consecutive year, bike sales exceeded motor vehicle sales in 2009 (ABC 2009). Research indicates there is a range of reasons for participating in cycling. There is a significant disparity in participation between genders. Female participation in cycling is significantly lower in Australia than many other countries – the rate of female commuter cycling is less than one third of the male rate. (Bell et al 2006). While the data shows mixed results in terms of progress over the past five years, the evidence suggests that cycling is growing in significance as a legitimate mode of transport in Australia. For example, ABC (2009) data showed a 47% increase in cycling on the top five commuter routes into capital city centres between 2005 and 2008.

Citations

• Australian Bicycle Council (2009): Annual Report

• Australian Bicycle Council data drawn from Cycling Promotion Fund (2010),

• Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009): Environmental issues: Waste Management and Transport Use, Cat. no.602.0.55.002

• Department of Health and Ageing and Australian Sports Commission (2008): Participation in Exercise, Recreation and Sport, Annual Report 2008

• Bell, C., Garrard, J. and Swinburn, B (2006) Active transport to work in Australia: is it all downhill from here?,Asia Pac. J. Publ. Health. 18 (1) pp. 62–68.

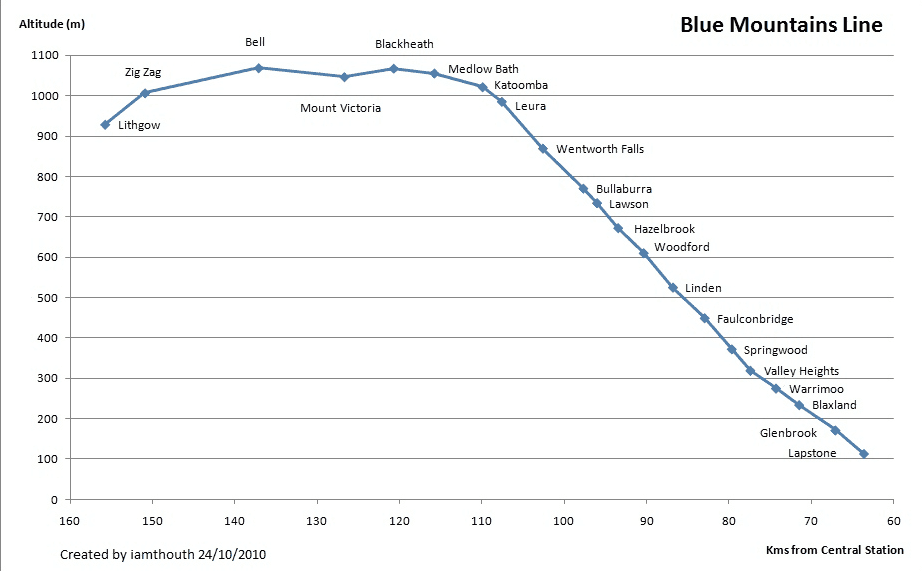

3. Demographics and Geography

The settlements in the Blue Mountains follow a narrow ridge serviced by the Great Western Highway and the Western Railway line. As such, few houses are more than a few kilometres from a Railway Station. Notably exceptions are Winmalee and the Megalong Valley. Direct train services from Cental are hourly to Katoomba, less frequent to Mt Victoria and even less so to Lithgow, where the electric train line terminates.

The region encompasses a total land area of 1,432 square kilometres, of which 74% is World Heritage National Park, renowned for its forests, rock formations, bushwalks, waterfalls and lookouts. A further 14% of the City is contained in public reserves. The City's major industry is tourism, with many holiday homes and guest accommodation in the upper mountain towns such as Blackheath, Katoomba and Wentworth Falls, while the lower mountain towns such as Blaxland, Glenbrook, Springwood and Winmalee, are more suburban in character. The main industrial estates are located in Katoomba and Lawson. The primary rural area is the Megalong Valley.

The population of the entire Council area was just under 77,000 in 2006 and is predicted to increase slightly to just over 78,500 by 2021, this represents a marginal population increase over the longer term. The residential areas that most likely to be effected by the GBMCTUM are Leura [4,343 people], Katoomba – Medlow Bath [8,708] and Blackheath and Surrounds [5,649] which represents a resident population of around 19,000 people currently that reside within close proximity to the identified route with this increasing to around 20,000 by 2021.

The Katoomba Region also has an array of inequalities compared to NSW as a whole, attributable to the regions pronounced level of socio-economic disadvantaged including:

• Katoomba has a 20 per cent greater death rate then would be expected for those less than 80 years old

• Premature death for females in Katoomba in the 25-75 age range (for all mortality causes) is 36 per cent above the rate for NSW and 42 per cent above the average for men.

• The rate of coronary heart disease experienced by males in Katoomba is 53 per cent above the rate for NSW

• Mental health suffers when social conditions are adverse. Katoomba is the only postcode in the Blue Mountains to have significantly higher rates of mental and behavioural disorders for 15-24 year-olds than the state average.

• Katoomba has the highest proportion of Blue Mountains families with children living off household incomes below $399 per week (17.6%). The state average is 13.2%.

• Despite geographical isolation and harsh winter conditions, 21.4 per cent of Katoomba households do not have a vehicle. The NSW average is 13.5 per cent.

• Single parent families comprise 15 per cent of all NSW families. Katoomba is well above this (24.3%) with more than a third of all Katoomba children (34%) living in single parent families.

• The proportion of households in Katoomba experiencing rental stress is 60.9 per cent. Rental stress is typically measured as an outlay greater than 30 per cent of total household income spent on rent.

The minimal population growth predicted in the area suggests local trail activity demand will not increase significantly as a result of local population growth and will be dependent upon visitor demand. The range of socio-economic indicators suggest the area has a relatively low socio-economic profile and given the characteristics of trail users (employed, higher income earners) it would be expected that demand for trail use from the local population would be lower compared with an equivalently sized area with a higher socio-economic status. However, this is not thought to be the case due to the local environmental sustainability focus of local residents. Furthermore, the need for the provision of low cost and alternate transport options such as cycling and walking trails is also higher in this area due to the high level of health issues, relatively low socio-economic status and lower levels of car ownership (Treadwell 2010).

Citations

• Treadwell (2010) Blue Mountains City Council Great Blue Mountains Trail: Upper Mountains Component : Feasibility Assessment Final Report.

4. Gundangurra Tribe

The world-famous Three Sisters landmark at Echo Point, Katoomba, is officially the 98th place in NSW to be declared of cultural, social and historic significance to the Aboriginal community.

The area down into the valley below the Three Sisters has traditionally been used as a ceremonial space with legend telling how the Three Sisters came to be the land formations they are today. The area is highly valued by the Aboriginal peoples of the Gundangurra, Wiradjuri, Tharawal and Darug nations.

Elders of the Gundangurra Tribe, the traditional custodians of the land over which the trail will run, have given their support to this proposal. Indeed, the trail should be named by the indigenous people of the Blue Mountains and signage should be made, describing significant Aboriginal history in the form of a 'discovery trail' of pre-European history and culture. Both, the Andersons and Oaks fire trails, which would form part of the Trans Mountains Trail, have significant Aboriginal caves with engravings and axe grinding grooves, which are already being managed by NPWS. The Cliff Drive section of the GBMCTUM also goes past 'the Gully'; important for recent Aboriginal history, where a vibrant community of Europeans and Aborigines co-existed until the 1950's.

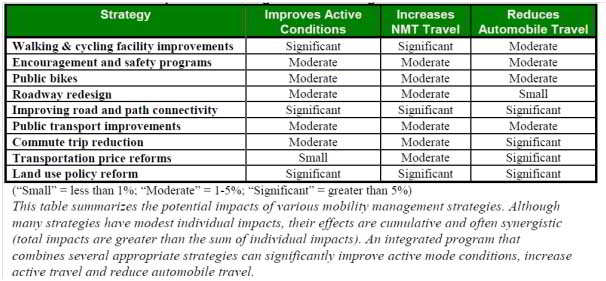

5. Active Transport

In most communities, 20-40% of the population cannot or should not drive due to disabilities, low incomes, or age. In addition, many trips, such as short errands, are most efficiently made by active modes. There is evidence of significant latent demand for active travel; many people want to walk and bicycle more than they currently do but face obstacles (ABW 2010). Active transport facility improvements often lead to more walking and cycling activity (FHWA 2012; Litman 2009b; Living Streets 2011). Similarly, there appears to be significant latent demand for housing in walkable communities (Leinberger 2012). Current demographic and economic trends (aging population, rising fuel prices, urbanization, growing traffic congestion, and increased health and environmental concerns) are increasing demand for active transport and the potential benefits from accommodating this demand (Litman 2006).

Travel impacts which encourage active transport

Citations

• ABW (2010 and 2012), Bicycling and Walking in the U.S.: Benchmarking Reports, Alliance for Biking & Walking (www.peoplepoweredmovement.org); at www.peoplepoweredmovement.org/benchmarking.

• FHWA (2012), Complete Streets (www.completestreets.org), provides information on multi-modal road planning. FHWA Bicycle and Pedestrian Program Office (www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bikeped) promotes bicycle and pedestrian accessibility, use and safety.

• Litman (2006), The Future Isn't What It Used To Be: Changing Trends And Their Implications For Transport Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/future.pdf; originally published as "Changing Travel Demand: Implications for Transport Planning," ITE Journal, Vol. 76, No. 9, (www.ite.org), September, pp. 27-33.

• Litman (2009), Where We Want To Be: Home Location Preferences And Their Implications For Smart Growth, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/sgcp.pdf.

• Litman (2011), "Adjusting Data Collection Methods: Making the Case for Policy Changes to Build Healthy Communities," From Inspiration to Action: Implementing Projects to Support Active Living, American Association for Retired Persons (www.aarp.org) and Walkable and Livable Communities Institute (www.walklive.org), pp. 104-107; at www.walklive.org/project/implementation-guide.

6. GBMCTUM as an essential link

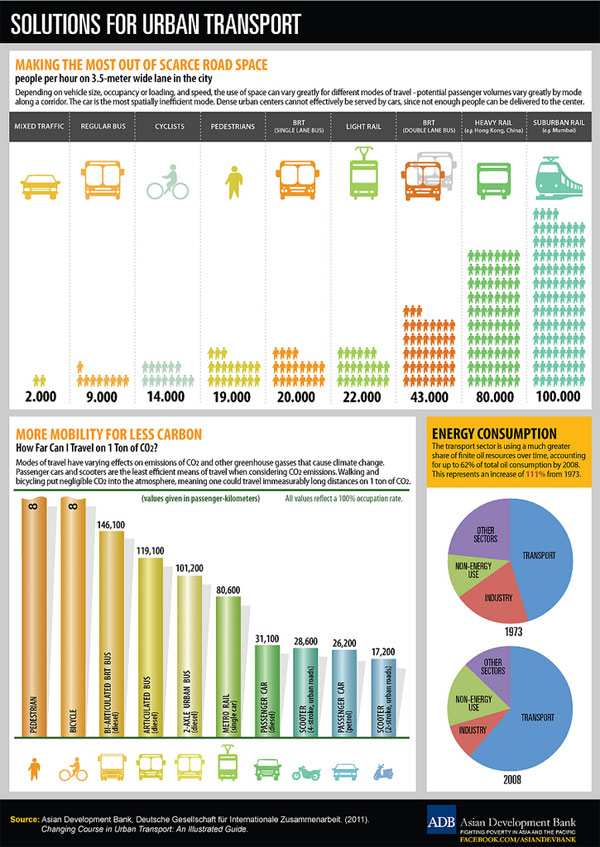

Transport systems tend to have network effects: their impacts and benefits increase as they expand. For example, a single sidewalk or bicycle lane generally provides little benefit since it will connect few destinations, but a network of sidewalks and bicycle lanes that connect most destinations in an area can be very beneficial. Similarly, a single sidewalk or bicycle path that connects two networks (i.e., it fills a missing link) can provide very large benefits.

Transportation improvement strategies also have synergistic effects, that is, their total impacts are greater than the sum of their individual impacts. The first few sidewalks, bike lanes or encouragement programs in a community will seldom offer a high economic return if evaluated individually, although once completed the network may provide very large benefits. It is therefore important to use comprehensive and systematic evaluation of active mode benefits.

The GBMCTUM represents the essential link between the cycling networks of the Sydney Basin and cycle touring possibilities west of the divide. For example, there appears to be little demand for the lower mountains Zig Zag connecting the Sydney Basin with the lower Blue Mountains. However, if this was also the connection with the entire Blue Mountains, including the Oaks and Andersons fire trails, the Wolgan Valley Rail Trail, with Lithgow and Bathurst, then we are looking at an international cycle touring icon such as "Bathurst to the Sea". Furthermore, the same trail project can also be seen in the light of a "Manly to Mudgee" 300km cycle trail, where the Sydney Basin cycle network is connected to Mudgee through the construction of 25km of GBMCTUM, upgrading 15km of the Wolgan Valley Rail Trail, signage through Cullen Bullen State Forest, and connecting with the yet-to-be-built Kandos to Mudgee Rail Trail, via the Glen Alice road. Hereby, you've connected communities physically and economically throughout this network. Moreover, a 300km network with a minimal investment in small connectors between pre-existing paths and trails can be made. Such an analysis must be of particular interest to Destinations NSW.

7. GBMCTUM rather than cycling on the 'unsafe' Great Western Highway.

The Great Western Highway between Katoomba and Mt Victoria represents a major national highway with large volumes of trucks and cars using one of only two crossings of the Blue Mountains. Currently, the highway is single lane with no shoulder. The high speed and large volumes of traffic (the annual average daily traffic (AADT) data for 2005, recorded 16,657 vehicle movements east of Narrow Neck Road and 16,368 vehicle movements south of Govetts Leap Road: RMS 2014) and limited space on the road make it a very dangerous proposition when considering its use by cyclists. The highway has been progressively upgraded over the past 3 decades. However, presently there are only limited plans for the upgrading of the highway along the stretch in the Upper Blue Mountains. Hence, the residents of the Upper Mountains are completely disconnected by any means of active transport. Furthermore, limited train and bus services make this disconnectedness even more acute.

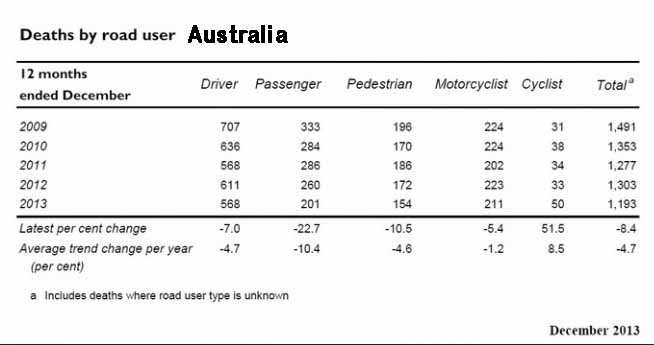

Cycling Rates are low, crash rates are relatively high and under-reported.

In Australia, transport-related deaths fell from 1,524 in 2008 to 1,477 in 2009. The majority of deaths (72% in 2009) were associated with motor vehicles driven on public roads. Pedestrian deaths fell from 206 in 2008 to 194 in 2009, while the number of pedal cyclist deaths increased from 26 to 35 (ABS 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2012). Cyclists are among the most vulnerable of road users. They have the highest proportion of self-reported near-miss crashes, which is significantly higher than that of motorists. The average probability of a cyclist being seriously injured in a collision was almost 27% - that's more than 1 in 4 crashes resulting in a serious injury (Wood et al 2009). In 2008, the majority of cyclist fatalities occurred on Sunday (21) and Friday (18), and 12-6pm was the most dangerous time for cyclist fatalities (CARRS 2011). The relative risk of injury on a bicycle is around 13-19 times higher than in a car over the four-year period (2002-5), which is broadly comparable to the results from Melbourne based on CrashStats data. It also appears that fatality risk may be greater for cyclists in Sydney, with more cyclists killed despite cycling rates of around half those of Melbourne (Garrard et al 2010). The cyclist fatality rate of between 4 and 7 per 10 to power of 8km in Sydney is several times greater than in the Netherlands (1.1 per 10 to power of 8km), Denmark (1.5) and Germany (1.7), though comparable to the USA (5.8) [Pucher J 2008]. The cyclist serious injury rate in Melbourne of between 124 (police data) and 315 (hospital data) per 10 to power of 8km cycled is very much greater than in the Netherlands (14), Denmark (17) and Germany (47), though, once again, comparable to the USA (375) [Pucher et al 2008]. A recent analysis reported a killed or seriously injured cyclist casualty rate of 54 per 10 power of 8km in Britain in 2008 based on police crash reports [Knowles J et al 2009].

Marshall and Garrick (2011) found that U.S. cities with higher per capita bicycling rates tend to have much lower traffic fatality rates, for all road users, than other cities. They conclude that this results, in part, because increased street network density both supports cycling and reduces traffic speeds and therefore risk. Robinson (2005), Geyer, Raford and Ragland (2006), and Turner, Roozenburg and Francis (2006) also find that shifts from driving to active modes by sober, responsible adults are unlikely to increase total accidents, and that per capita collisions between motorists, pedestrians and cyclists decline as active transport activity increases.

Various studies indicate that automobile external accident costs average 2¢ to 12¢ per vehicle-mile, depending on driver and travel conditions, and the scope of costs considered ("Crash Costs," Litman 2009; van Essen, et al. 2007; TC 2008). Net safety benefits provided by automobile to active travel shifts are estimated to average 5¢ per urban peak mile, 4¢ per urban off-peak mile, and 3¢ per rural mile, with greater benefits from strategies that reduce walking and cycling risk, for example if active travel increases due to more separated facilities (e.g., sidewalks and paths), traffic speed reductions, improved traffic law enforcement and cycling education.

The statistics into cycling injuries in the Upper Blue Mountains are more difficult to find. However, as speed is purported to be a major factor in cycling injury and even death, then it would well be worth hypothesising the risk to a cyclist if they were fool hardy enough to use the GWH where the speed zones are up to 80km/hr.

Source : RMS 2014

Interestingly, similar to the sections between Katoomba and Blackheath, speed was the major cause of crashes, both in the township as well as between towns. In the section of highway between Blackheath and Mt Victoria, it is expected that cyclists share the road with vehicles moving at 80km/hr. Apart from the lack of cyclists on this stretch of road due to its inherent danger, all the crash statistics involving cyclists are likely to be under-reported due to the inclusions criteria used (see below).

It should be noted that not all bicycle accidents involve car collisions, which may also contribute to under reporting of cycling accidents, as found by Richardson DB (2009). While road safety counter-measures have undoubtedly led to a safer operating environment for vehicle occupants, the (arguably) car-centric nature of many of these measures has in fact done little to improve cyclist safety. Cyclists appear to be over-represented in terms of fatalities and serious injuries relative to their exposure to traffic, but under-represented in interventions aimed at reducing traffic fatalities and injuries (Garrard et al 2010).

Trails beside Rail:

In the USA, there are more than 21,000 miles of rail-trails across the country, in urban, suburban, and rural areas. But these trails don't need to be built on the graves of defunct rail lines. A growing number of them, in fact, are constructed next to active rail lines. In 1996, there were slightly less than 300 miles of these trails. Today there are about 1,400 miles. Railroads tend to be skittish about approving walking and biking routes because they fear liability if someone gets injured. Even so, 43 percent of rails-with-trails, as they're known, are located wholly within railroad rights-of-way, while another 12 percent have some segments inside the right-of-way.

By planning for mobility along and even across railroad tracks, railroads can help prevent some of the 430 fatalities that occur each year when people cross tracks where they shouldn't. In its comprehensive study of rails-with-trails, the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy found only one record of a fatality (and two injuries) on such facilities in 20 years:

This suggests that providing a well-designed pathway dedicated for cyclists and pedestrians provides a safe travel alternative and reduces the incentive to trespass or use the tracks as a shortcut. Such pathways often include some form of barrier between the trail and the active railway, and carefully-planned intersections if the trail crosses the tracks.

http://usa.streetsblog.org/2014/08/18/why-it-makes-sense-to-add-biking-and-walking-routes-along-active-rail-lines/

Garrard et al (2010) concluded the following :

International experience demonstrates that cycling safety can be improved markedly using the same sort of strategic planning that has been used to improve safety for car occupants [6]. Improved cycling conditions that are likely to contribute to increased cycling safety include:

• more extensive, high quality and well-maintained cycling infrastructure, including separated cycling facilities

• basing priority systems on needs of vulnerable road users (where appropriate), rather than car occupants

• improved interactions between cyclists and drivers in the form of mutual respect, courtesy and willingness to share public road space

• education and training for drivers and cyclists aimed at improving skills, attitudes and behaviours

• urban speed limits based on human tolerance to injury in collision with a motor vehicle

• placing greater responsibility for traffic safety through the legal system on those road users who have the potential to cause the most harm to others.

Hence, we are calling for the construction of a segregated cycle path similar to the one built along the M7, using rail corridors (Blackheath - Mt Victoria), existing unsealed roads as well as the 'upgrading' of the 'adventure trail' track which is about to be built (commencing September 2014) by BMCC.

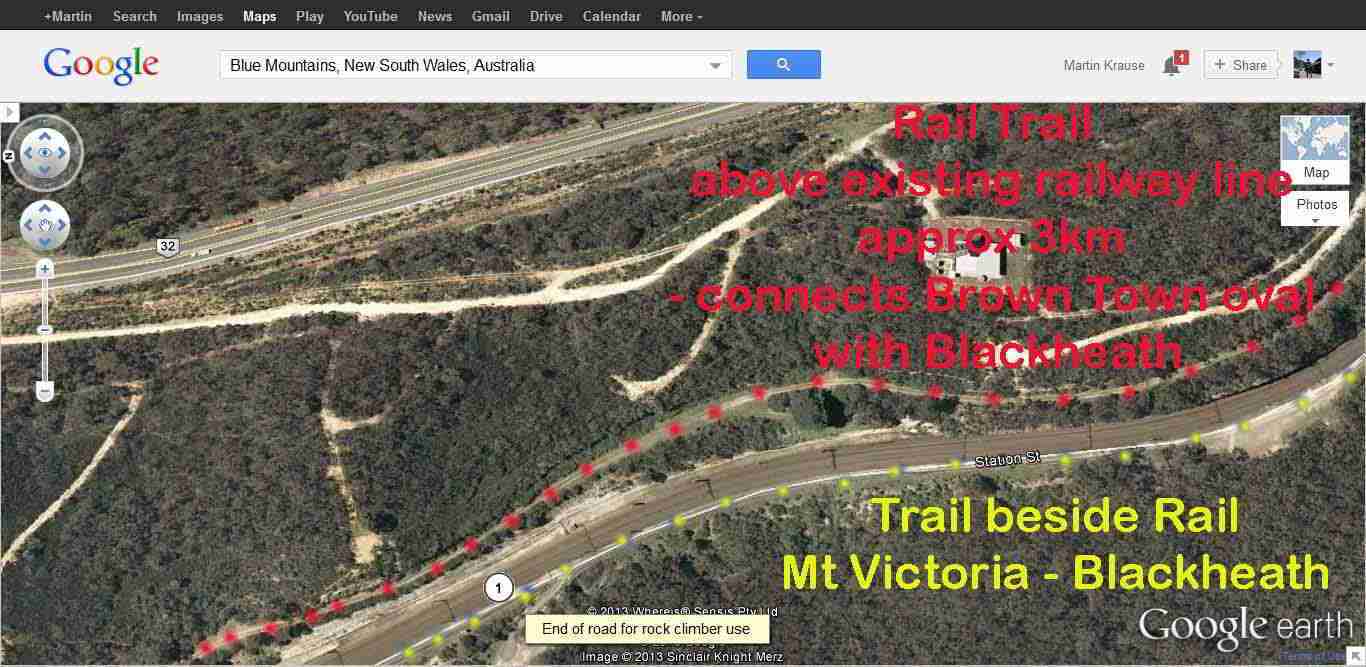

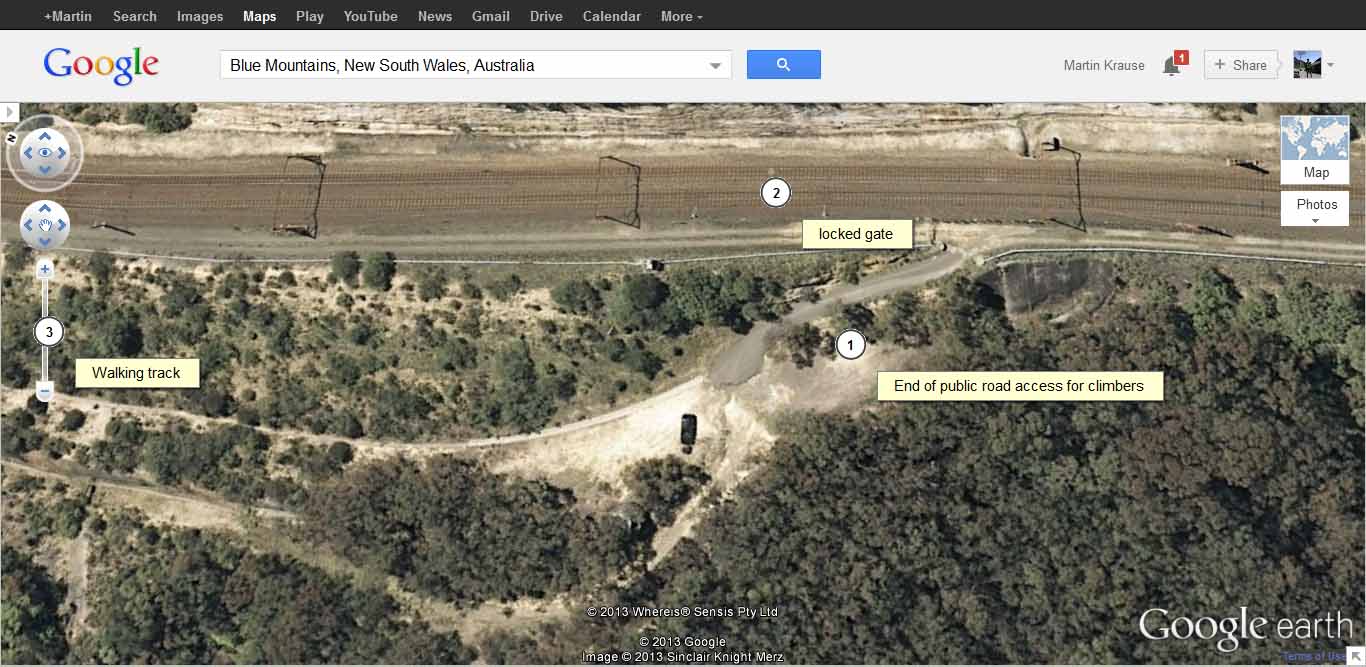

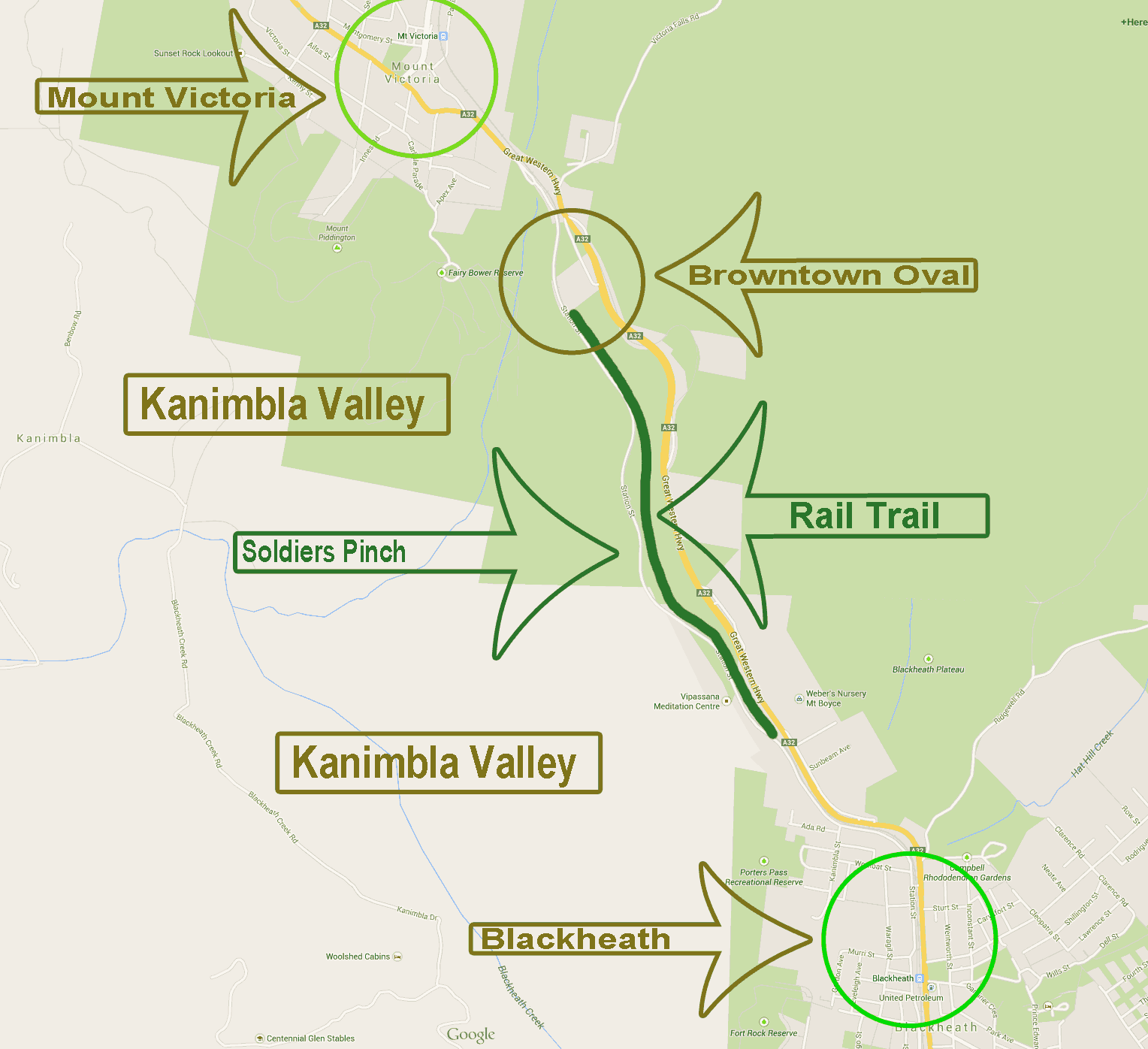

Trail beside Rail or a Rail Trail : Blackheath - Mt Victoria

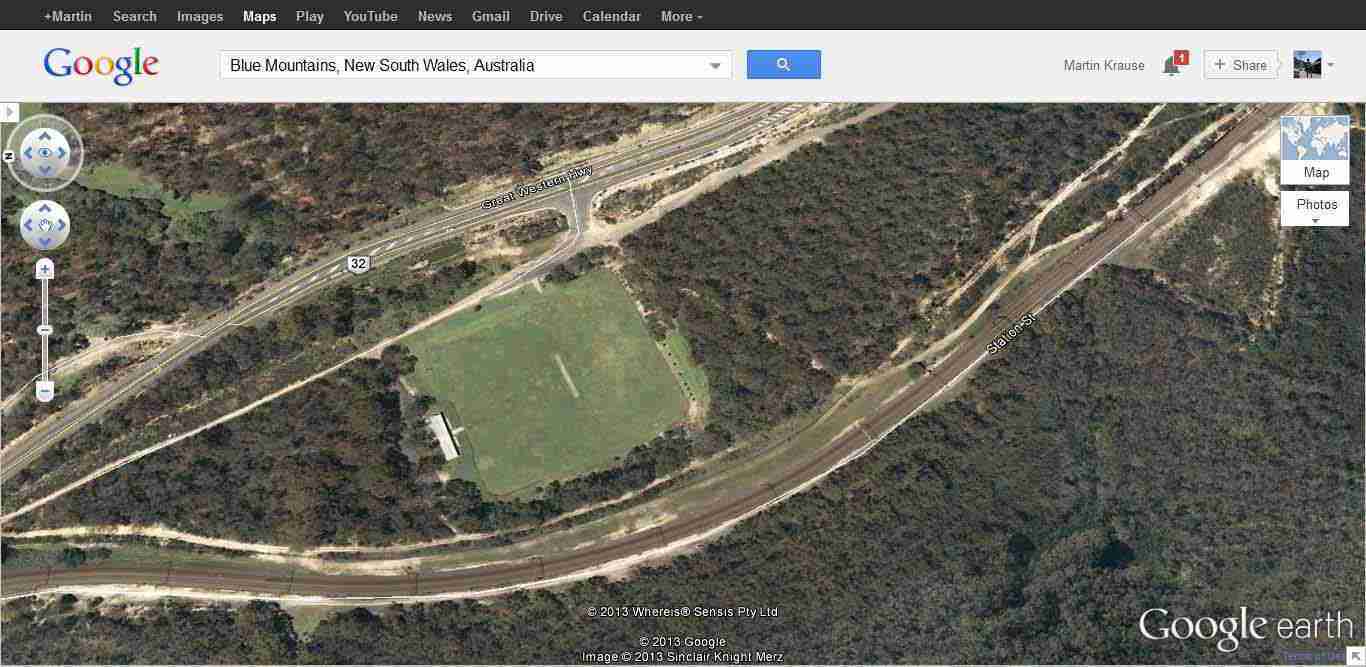

There appears to be two distinct possibilities for the trail westward of Blackheath. Either, using the Trail beside Rail on the south western sde of the Railway Line or a Rail Trail on the north eastern side of the line. The latter is completely separated from the Railway Line but still falls within the rail corridor. It would connect Brown Town Oval with Blackheath. It would need access pathways at Blackheath township, which become part of the highway upgrade. Similarly, the Rail Trail needs to cross the railway line at the same location as the GWH does at Mt Victoria and hence the bridge there would need pedestrian/cyclist path widening or an electric boom gate could be installed at Railway line level near Fairy Bower reserve.

Two ways or create a round trip? Looking west at the Vapassana meditation centre

Trail beside Rail between Blackheath end and Mt Victoria

Liability issues negated

Map describing permited access to the Trail beside Rail

Two possibilities - a Rail Trail to the left (north east) of the tracks separated from trains or the Trail beside Rail on the right (south west) side of the tracks (this picture is looking east)

An historical 3.6km of Rail Trail along the disused original railway easement - currently hidden by Rail Corp.

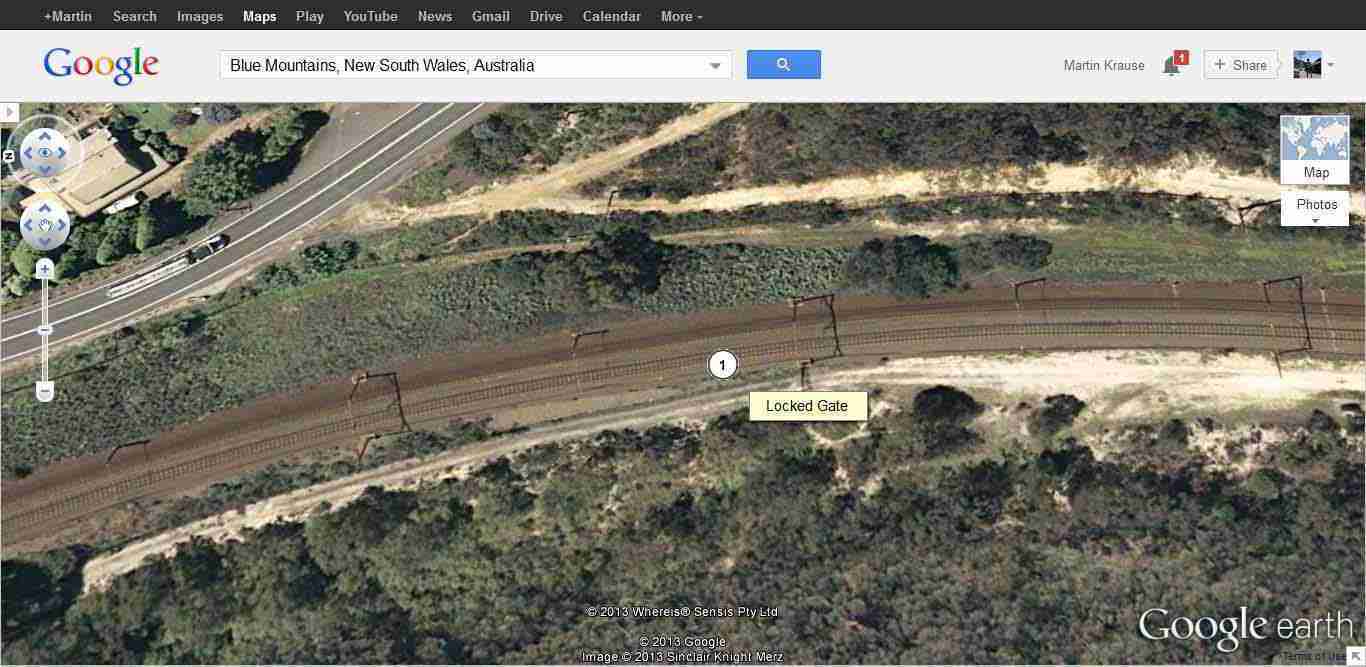

Highway near Mt Victoria and Brown Town Oval with locked gate on the trail beside rail (1) and on the opposite side the commencement of the Rail Trail

Brown Town Oval - Rail Trail on same side as oval; Trail beside Rail on opposite side of the tracks

A small section of tracks at Mt Boyce where the Rail Trail (between the tracks and highway) and the Trail beside Rail (1) can quite clearly be seen

existing 900m of unfenced locked off area of Trail beside Rail

In contrast, a Rail Trail above and away from existing railway line

Spectacular 'world class' views of the Megalong and Kanimbla Valleys and Jenolan Forest in the distance

Rail Trail cutting viewed from above

Rail Trail cutting with cyclist heading towards Blackheath on gentle railway gradient

Locked Gate and Car Park for Rock Climbing

The only impediment to a trans-mountains trail is the opening of the rest of this track (900m). Currently, over three quarters the track is open for use and has been since the 1990's. In that time, there hasn't been a single incident involving trains, maintenance vehicles and rock climbers accessing this area. The usual excuses for not opening the remaining track are 'emergency access', 'liability' and 'signalling'. At this point, I would think upgrading the trail will improve access to emergency and maintenance vehicles. Liability has been dealt with for years with the above signage and I'm sure working around signalling isn't a major engineering feat.

Alternatively, there is the Rail Trail on the opposite side to the Trail beside Rail which would be even better. If it were possible to have both then a round trip would be possible. During the current upgrading of the GWH at Mt Victoria and at Blackheath, the RMS would need to build a short path in Blackheath and Mt Victoria in addition to providing a safe cycle and pedestrian crossing of the Railway Line on the GWH bridge at Mt Victoria. The Rail Trail would also solve the much vexed issue of peoples inability to use active transport to reach Brown Town Oval.

The Mt Victoria end of the track looking south east.

Fairy Bower and Mt Piddington Nature Reseve, at the Mt Victoria end of the trail.

The beauty of the cycling trail alignement is that it allows for dual mode transportation of bikes with trains.

Citations

• Centre for accident research and road safety, 2011, State of the Road: Bicycle Safety Fact Sheet

• Garrard J, Greaves S, Ellison A 2010 Cycling injuries in Australia: Road safety's blind spot? Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety – August 2010

• Jacobsen P 2003, "Safety In Numbers: More Walkers and Bicyclists, Safer Walking and Bicycling," Injury Prevention (http://ip.bmjjournals.com), Vol. 9, pp. 205-209.

• Knowles J et al 2009. Collisions involving pedal cyclists on Britain's roads: Establishing the causes. United Kingdom: Transport Research Laboratory

• Litman T 2009, Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis Guidebook, VTPI (www.vtpi.org/tca).

• Marshall WE and Garrick NW 2011, "Evidence on Why Bike-Friendly Cities Are Safer for All Road Users," Environmental Practice, Vol 13/1, March; at http://files.meetup.com/1468133/Evidence%20on%20Why%20Bike-Friendly.pdf

• Pucher J, Buehler R. Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transport Reviews, 2008; 28(4), 495-528

• Richardson DB 2009 Amalgamation of police and hospital trauma data in the Australian Capital Territory. Canberra: Australian National University Medical School

• Robinson D 2005, "Safety in Numbers in Australia: More Walkers and Bicyclists, Safer Walking and Bicycling," Health Promotion Journal of Australia, Vol. 16, No. 1 (www.healthpromotion.org.au), April, pp. 47-51.

• RMS (2014) : http://www.rms.nsw.gov.au/roadprojects/projects/western_region/mt_victoria_lithgow/documents/140422_potential_treatments_report.pdf

• Turner SA, Fleming T (Allatt), and Tarjomi L (2013), Reallocation of Road Space, Research Report 530, NZ Transport Agency (www.nzta.govt.nz);

• S.A. Turner, A. P. Roozenburg and T. Francis (2006), Predicting Accident Rates for Cyclists and Pedestrians, Land Transport New Zealand Research Report 289 (www.ltsa.govt.nz); at www.ltsa.govt.nz/research/reports/289.pdf

• Turner, R. Singh, P. Quinn and T. Allatt (2011), Benefits Of New And Improved Pedestrian Facilities – Before And After Studies, Research Report 436, NZ Transport Agency (www.nzta.govt.nz); at www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/research/reports/436/docs/436.pdf

.• van Essen HP et al. 2007, Methodologies For External Cost Estimates And Internalization Scenarios: Discussion Paper For The Workshop On Internalisation On March 15, 2007, CE Delft (www.ce.nl); at www.ce.nl/4288_Inputpaper.pdf

• Wood, J.M., Lacherez, P.F., Marszalek, R.P., & King, M.J., 2009, Drivers' and cyclists' experiences of sharing the road: incidents, attitudes and perceptions of visibility, Queensland University of technology, http://eprints.qut.edu.au/29579/1/29579.pdf, p.3

Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail and Soldiers Pinch

An Historic Rail Trail Built In The 1860’S

: NSW Rail Trails submission 2014

A preliminary submission to notify Rail Trails for NSW to the existence of a long forgotten disused section of the original trans mountains railway line. Built during the age of steam by the Tasmanian contingent of Royal Engineers and opened circa 1867 between Blackheath and Mount Victoria at the top of the New South Wales Blue Mountains.

The Blackheath to Mt. Victoria is a unique Rail Trail that has remained isolated in time and detached from progress and development for over 115 years. It not only offers a fantastic opportunity to see back in time to the early engineering and pioneering development of the area, but also further back in time to the first Australians to also share in their history of the region delivering a dynamic visitor experience.

Combined with this history are the splendid uninterrupted picturesque views within this world Heritage Area and of the beautiful Kanimbla Valley below.

Innovative opportunities to develop tourism and grow employment are greatly needed in our region and the Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail will provide a positive return on investment through the delivery of funds and grants on this very special Rail Trial.

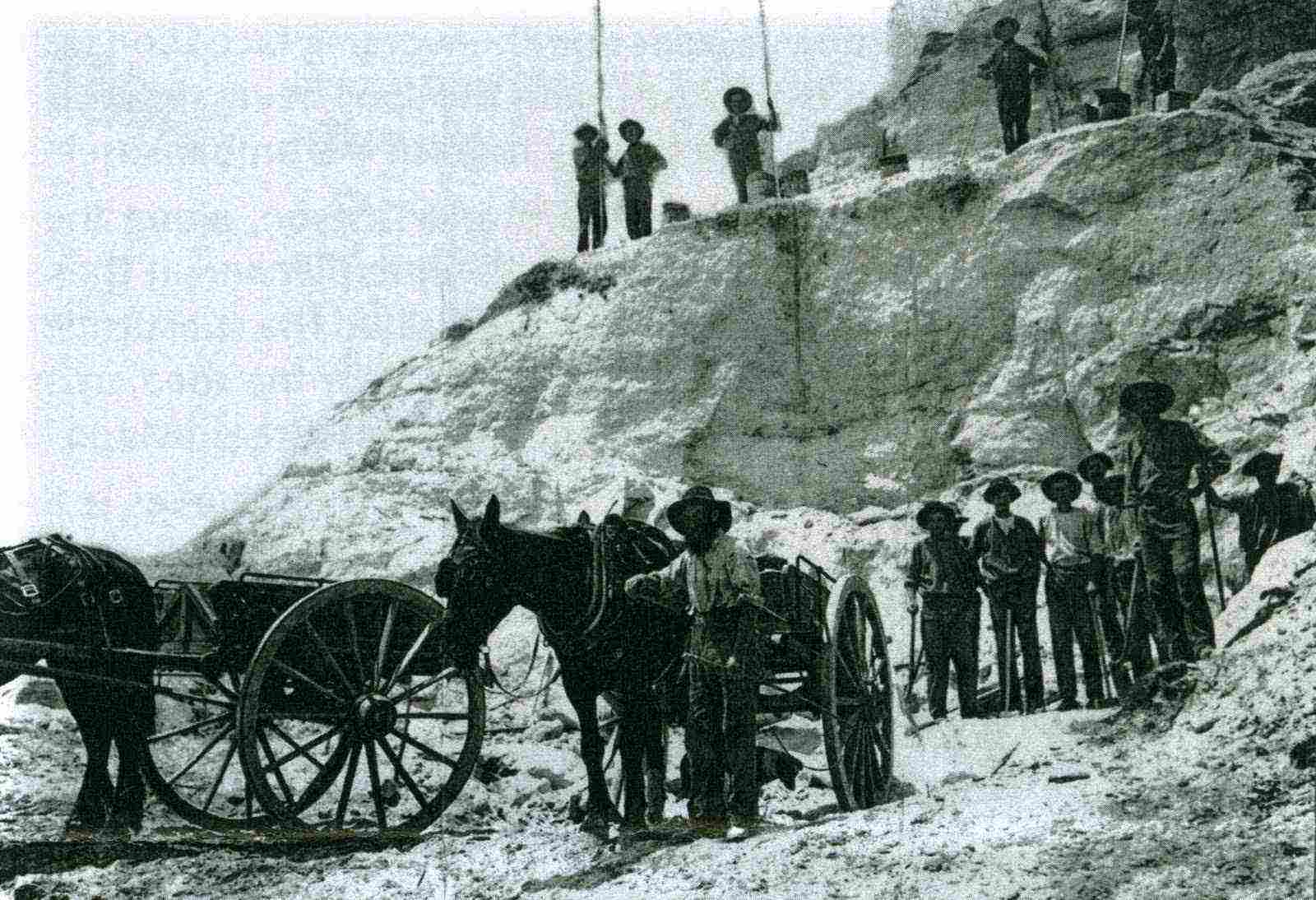

Historical Perspective : Due to the lack of civilian surveys in the 1860’s, the Royal Engineers from Tasmania were deployed in Western Sydney New South Wales to scope, survey and build a rail line stretching from the town of Parramatta out west to the rapidly growing township of Bathurst. This meant crossing the greater Blue Mountains that is well over 1000 meters in height. In stark contrast the Blue Mountains, western line from Parramatta to rural area of Emu Plains just past the major township of Penrith could not be any more different. Here it was predominately flat and required little creative engineering other than a viaduct and a small number of bridges.

The track from Emu Plains to the other side of the mountains towards the first main township of Lithgow on the other side of the Mountains however was considerably different. This meant scaling a mountain over one kilometre high. It would require considerable engineering, viaducts and bridges to get to the top at Blackheath and Mt. Victoria some 120 kilometres from Central Station in Sydney. Lapstone was considered the first stop on the Mountain.

Along multiple locations across the Blue Mountains the route has breath taking views across several valleys and escarpments including the Jamison Valley, Megalong Valley and Kanimbla Valley just to name a few.

This line began opening around 1867 as single-track railway line that lasted unchanged and in constant use for the next 30 years. As the demands for the service crossing the Mountains increased along with the ability to build a better rail network, a survey was commissioned in 1896 to improve the grades and curves across the Blue Mountains.

Work commenced on the line improvements in 1897 and they were completed around 1903. Several interesting sections of the original rail line were annexed from the active line. The most significant of these is between Blackheath and Mt. Victoria as result of what was known as The Soldiers Pinch Deviation. Here a second dual line was created below the original single that was decommissioned.

Near the very top of the Mt. Victoria Pass between Mount Boyce and Browntown Oval is an area called Soldiers Pinch. It was named after a story of an unfortunate soldier involved in an accident that may have occurred well before 1839 during the formation of the original carriageway. This soldier unwittingly placed his foot under a very heavy wheel to block it instead of a stone. According to G Whalan’s Trip over the Mountains several years later, his foot was subsequently ‘crushed to atoms’. It is believed that the unfortunate soldier died as a result.

Unique Features

Due to the isolation of the track in this remote region of the Blue Mountains, several significant historical features of the potential Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail including the Soldiers Pinch section remain today as it was in the late 1800’s. With no further public works or reuse for other activities other than occasional emergency vehicle access, this former rail line has been left silent. Less only rail sleepers, it has been preserved in its original state for over 115 years. Many old steel sleeper pins can be found strewn across the trail.

One of the features that make Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail a rare example is that the culverts are made of heavy sandstone at both ends, where most that are still found across NSW have been refurbished on at least one side with bricks.

Sandstone Culverts along the Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail

Culverts are drainage tunnels that carry runoff water from one location to another. The most common sources of the water are natural rainfall and storm water and the most common use of the culvert is to carry the runoff under a road or railway line.

Large culverts have been built to carry streams. Culverts in the Blue Mountains have been constructed with wood, stone, brick and more recently concrete. Sandstone culverts range in width from 450 mm (1 ft 6 inches) through the most common 600 mm (two foot) to less common 900 mm and on up to 2700 mm. The first railway line came through Blackheath in the late 1860s and many sandstone culverts were built at that time. These were mainly 600 mm wide sandstone culverts, commonly known as box culverts. As Blackheath grew and the second rail line came through in the early 1900s, the roads were modified and sandstone culverts suffered badly. In most cases either the entrance or exit was extended with brick and sometimes concrete, some entrances were grilled to stop access, and sometimes access was restricted by earthworks. As a result it is now unusual to find an intact sandstone culvert in its original condition. There do not appear to be any such between Medlow Bath and Blackheath and none in the immediate vicinity of Blackheath village itself. However, around Mount Boyce on the eastern side of the current railway line there is a stretch of disused line from which the rails have been removed and which appears to have remained largely undisturbed over the last hundred years. It contains several cuttings and at least seven pure sandstone culverts.

It runs parallel to the existing line and about 15 m to 20 m to its east. It rises from being about 3 m above the line close to Mount Victoria to being around 10 m above the line close to Mount Boyce. The course of the track is indistinct at both ends where extensive earthworks have been carried out however there is a section of about 2 km that has been minimally damaged. It is here that the sandstone culverts are best seen. Due to the culverts being located away from the current rail line we have simply given them sequential numbers with the prefix S. These are sequential and increase with distance from Blackheath. Location details are tabulated at the end of this work Sandstone culverts were constructed with rectangular handmade blocks of sandstone. The floor of the culvert is usually composed of three parallel rows of sandstone slabs laid lengthwise.

The floor has a slight fall over the length of the culvert. While this fall is sufficient for water to drain away, it is sometimes insufficient to maintain solids in suspension, resulting in build up of sand, soil and vegetation and ultimately to the blockage of the culvert. Maintenance procedures on active rail lines include the regular inspection of culverts and debris clearance where necessary. Partially and totally blocked culverts are commonly encountered on abandoned sections of a line

Tourism

The Blue Mountains Rail Trail is a short but very historically significant 2.5km section of rail bed. It is in original condition since the sleepers were removed around 115 years ago, untouched by any further development.

This section of trail is perfectly accessible by townships and train stations at both ends of the trail, plus it is linked into other bike trails both eastern and western ends. Uninterrupted mountains and valley views adorn the trail limited only by the technical ability of a visitor’s camera to capture these stunning views. A strong variety of ‘money’ shots exist to expose this area on international and domestic tourism brochures.

Of the six local indigenous nations, 2 are well represented in the area. They are in support of the Rail Trail and are interested in providing information relative to their history where appropriate along the Rail Trail and surrounding trails. History of the first explorers and most importantly the history of the rail line can be sign posted along the way.

The Rail Trail would become part of a network of trials currently in planning and under construction crossing the Blue Mountains. Interlinking shared bicycle/pedestrian pathways are being constructed between upper Blue Mountains villages providing access to the Rail Trail by Road, train and bicycle. The Blue Mountains is an important link in the greater Manly to Mudgee vision. The Blackheath to Mt. Victoria Rail Trail would be the jewel in the crown.

Leading the charge is the Blue Mountains City Council with their 2020 Bike Plan and a number of very enthusiastic bike groups advocated by the Blue Mountains Connected Communities Alliances Sustainable Transport Group.

Making the track accessible will require some rerouting and possible pedestrian/cycle bridge at the eastern end across the rail line at a location where the rail line is deep down in the cutting, making the construction of such an asset much cheaper than it would be if on the same plain. Although this would be the most logical and interesting solution, other viable alternatives exist. Sections of the Rail Trail establishment are a perfect fit for the work for the dole scheme.

Economic modelling for the rail trail has not yet been completed, however the number of tourists that may be attracted to the region could be around 2000 per month and many of these would be encouraged to stay for at least one night or extra night to their stay. This could increase overnight stays by around 3-5% per annum. This would provide a significant return on investment and a boost to the local economy each year in the tens of millions.

Data from 2011 census shows that unemployment in the upper Mountains was at least 50% higher than the national average of 5.6% with Katoomba at 8.4% and Mt Vic at 7.7%

The establishment of the Blackheath to Mt. Victoria rail trail would boost the local economy and offer more employment and business opportunities to residents particularly to those unable to commute long distances. The development of the Rail Trail supports the NSW government's regional growth plans as well as the Blue Mountains City Councils 2020 Bike Plan. The stated target of increasing employment in the Blue Mountains subregion from 2001 levels of 19,000 to 26,000 by 2031 - up by 7,000 in the Economy and Employment North West Key Directions document would also be supported.

Rail Trails in other areas have provided tangible evidence that formal Bike trails of any kind have had a very positive impact on tourism.

Lower Blue Mountains Rail Trail and Zig Zag Rail Trail

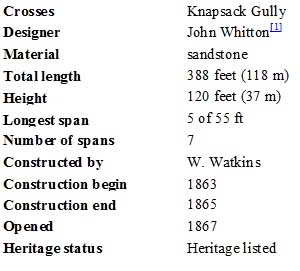

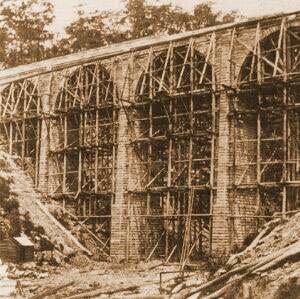

The Lapstone Zig Zag was a zig zag railway built near Lapstone on the Great Western Railway of New South Wales in Australia between 1863 and 1865, to overcome an otherwise insurmountable climb up the eastern side of the Blue Mountains. The ruling grade was already very steep at 1 in 33 (3%). The original plan had been to build the whole line across the Blue Mountains on a completely different route through the Grose Valley with a 3 km long tunnel, but this was beyond the resources of the colony of New South Wales at the time. The track included a now abandoned station called Lucasville which was built for the Minister for Mines, John Lucas who had a holiday home nearby.

Blue Mountains council has already made some investment in cycling infrastructure in the region of the lower Blue Mountains Zig Zag Rail Trail

Note that the lower part of the Rail Trail has already been sealed by Penrith council. This would be the natural gateway to the Trans Mountains Cycle Trail

The Trail deteriorates into a dirt trail which is discontinuous and has 2 alternatives. The first is the Zig Zag which eventually leads to exit of the Glenbrook tunnel via Lucasville Station. The alternative possibility is to reopen the old Glenbrook tunnel.

<pstyle="text-align:center">

The 660.3m long Old Glenbrook Tunnel was built between April 1891 and December 1892 as part of a deviation which bypassed the Lapstone Zig Zag. To save money, a ventilation shaft was not included as it was believed the current of air passing through it would provide sufficient ventilation. This soon proved to be not the case. The gradient of the S-shaped single-line tunnel was, at 1 in 33, quite steep. Seepage kept the rails wet, leading to slipping and stalling. These shortcomings and the growing need for a second line led to the establishment of a new route through Glenbrook Gorge in 1913 which included a replacement tunnel.

https://www.facebook.com/glenbrooktunnel/

July 2021 : great news - Glennbrook tunnel to be reopened as a cycle trail

See article in Blue Mountains Gazette : https://www.bluemountainsgazette.com.au/story/7323551/historic-rail-tunnel-to-be-opened-to-community-following-new-funding-injection/

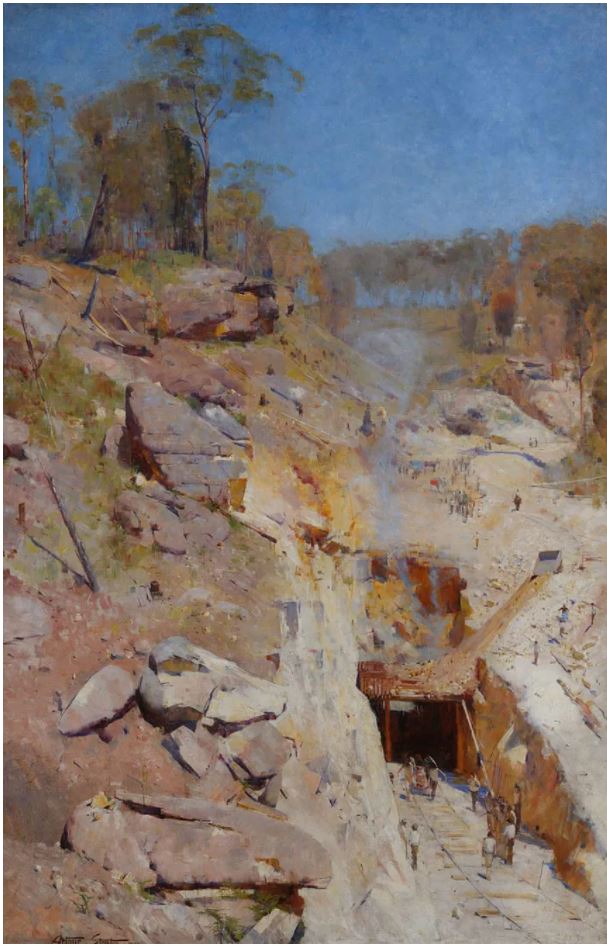

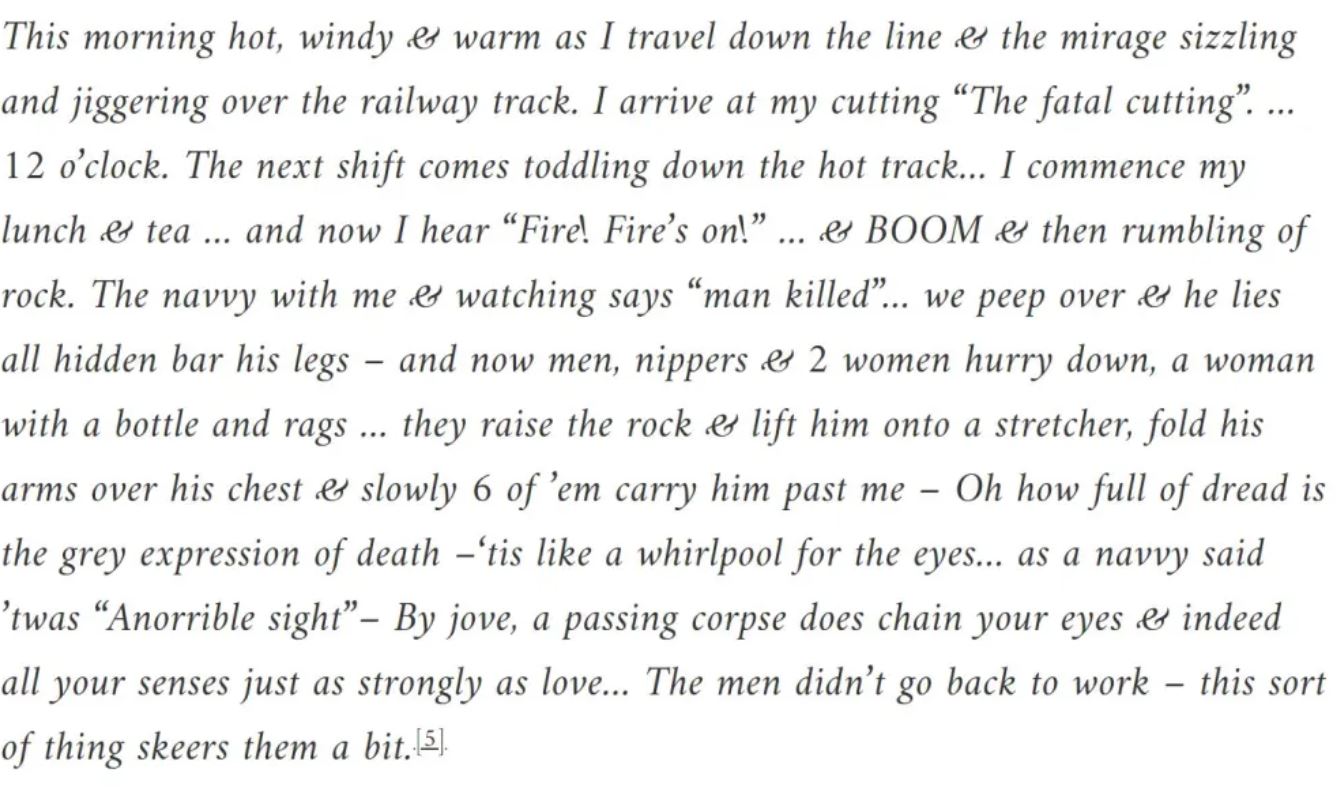

The most famous Arthur Streeton painting, 'fire's on', of the Glenbrook tunnel construction and the accident which claimed the life of a labourer.

In 1938 the painting was part of an exhibition at the National; Gallery. Lionel Lindsay interpreted it in this way;

‘….but the hero of this picture is not the poor fellow borne out by his mates, it is the Australian sunlight of a cloudless day, wide on the hillside.

Held down by the impenetrable blue of the sky, without chiaroscuro, and with only the crisp shadows of the sandstone to link his composition, Streeton has created a blaze of light on the broken hillside. By his gift of colour, by exactitude of values, and dexterity of touch, he has forced the yellows and bleached surfaces of earth upon a foil of warm-grey rocks, to yield a higher note of heat and light.’

Soon after completion the painting was purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where it is still held.

The tunnel was anything but a success. In 1913 it was closed and during WWII it was the sight of 'covered up' a gas tragedy. The gradient was too steep for trains and frequently passengers were asked to alight to reduce the load. Hopefully, soon it will be the gateway to the Blue Mountains cycling trails and will bring a sense of enjoyment and pride which unfortunately, the early settlers hadn't experienced. Hence, the mans death won't be in vain. Perhaps a plaque to all the workers should be erected there? I also think the cutting could have a climbing garden on one side of it.

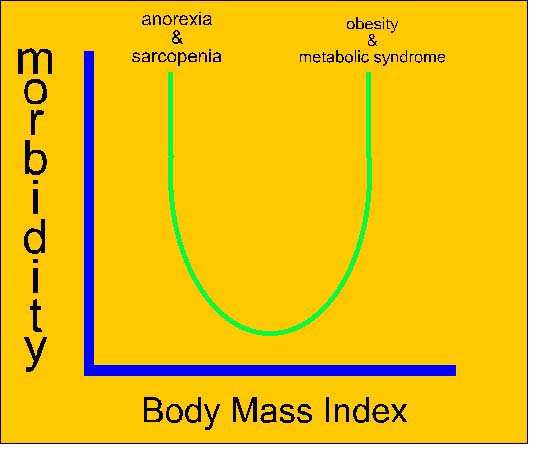

8. Health

Unhealthy lifestyles, including poor nutrition, lack of exercise and stress have led to an epidemic of chronic illness commonly referred to as 'metabolic syndrome'. These illnesses include hypertension, hypercholesterol, heart disease, and diabetes frequently associated with weight gain and obesity. Depression and anxiety related disorders can also be impacted by a sedentary lifestyle and have been associated with either excessive weight loss (anorexia and sarcopenia) or gain. These illnesses have a high rate of morbidity that creates major economic and social burdens on society.

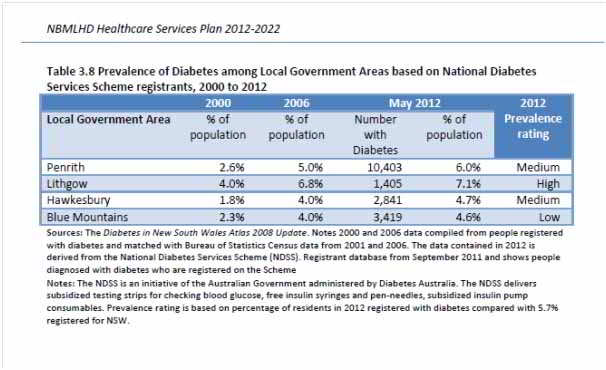

Diabetes

The Blue Mountains Eye Study examined 3654 residents aged 49 + years (82.4% response rate) during 1992–1994, and re-examined 2335 (75.1% of survivors) during 1997–1999 and 1952 (75.6% of survivors) during 2002–2004; 2123 participants with normal blood glucose levels at baseline were considered at risk of developing incident diabetes. The overall 10-year incidence of diabetes and IFG was 9.3% and 15.8%, respectively. Participants with metabolic syndrome at baseline had a higher risk of incident diabetes than those without metabolic syndrome (29.2% v 8.6%). Baseline factors associated with incident diabetes were elevated fasting glucose level (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 4.5; 95% CI, 3.4–6.1 per mmol/L), obesity (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3–2.8), diabetes family history (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5), current smoking (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0–2.7) and high density lipoprotein cholesterol level < 1.0 mmol/L (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.5–3.8). Similar baseline factors were associated with incident IFG. They concluded that this population-based study provided data on the incidence of diabetes and IFG in an older, predominantly white population, and confirmed that metabolic and lifestyle factors are major risk factors for diabetes. (Cugati S et al 2007).

It is noteworthy, that the incidence of diabetes in the Blue Mountains appears to be low. This is in contrast to the feasibility study by Treadwell (2010) which claimed it was higher than average. This may be attributable to the generally more active lifestyle of the Upper Mountains residents? Regardless, the health of the surrounding areas may be impacted by a trans-mountains cycle trail bringing activity conscious healthy people into areas such as Lithgow and Penrith, as well as presenting cycling opportunities to these people.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is the gradual loss of muscle mass, commencing in the 4th decade of life. On average 1% muscle mass is lost irreversibly per year in muscles which are inactive. This accelerates after the 6th decade of life. The consequences are numerous, including reduced physical loading capacity and tolerance, reduced protein reservoir for the immune system and reduced capacity for the absorption of insulin. Frailty can lead to falls in the elderly, where hip fractures have a 25% morbidity rate and another 25% never leave some form of care. Regular (every 72hours) exercise can ameliorate the loss of muscle mass as well as provide an alternate metabolic pathway for the absorption of glucose through the use of Glut-4 receptors. Hence, the provision of a cycling trail on a gradient similar to a railway line would allow people to maintain their muscle mass through regular exercise.

Pollution

Pollution is known to cause respiratory distress. It is also known to increase the risk of artherosclerosis which can lead to stroke and heart disease. Provision of a cycling network may reduce congestion and pollution on the roads.

Mental Illness

The incidence of mental health issues are thought to be higher than the average (Treadwell 2010). Socialising and exercising have been shown to help reduce some mental health symptoms. The great aspect of cycling along a segregated trail, is the ability to enjoy a conversation whilst not worrying about being hit by speeding noisy traffic, thereby allowing the natural endorphins in the body to be released.

The rate of hospitalisation by diseases, which can be ameliorated by exercise, such as endocrine and metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and musculoskeletal diseases appears quite high. Reduction of these diseases, which represent a relative large economic health burden on society, through regular exercise, allows precious health dollars to be spent elsewhere.

Musculoskeletal Disease

Musculoskeletal diseases such as knee and hip arthritis can quite frequently be helped through low impact low weight bearing exercise such as cycling because it aids joint lubrication, blood flow and prevents muscle atrophy, thereby maintaining joint stability. Cycling also can reduce the biomechanical loading on the joints through the burning of calories which leads to weight loss.

The severity of all these conditions can be reduced and better managed through regular endurance exercise such as cycling. Thus, investing in cycling infrastructure should reduce the economic health burdens on society.

The health and the environmental benefits of an active lifestyle are well documented (US Department of Health & Human Services 1996; Warburton 2006; Gotschi 2011). The growing levels of concern about increasing obesity, rising rates of chronic disease, climate change, and the environmental impact of continuing to rely on fossil fuels for transport have made the case for promoting physical activity across whole populations even more compelling (Guo & Gandavarapu 2010; Gotschi 2011; Gortmaker et al 2011). Walking and cycling for transport is one way with considerable potential to address a wide range of these costly health and environmental issues (MacMillan 2012)

According to Bauman et al (2008) the direct gross cost of physical inactivity to the Australian health budget in 2006/2007 was around $1.49 billion. Other Australian studies have reported that insufficient physical activity was the third largest single determinant on the Burden of Disease Scale in Queensland (Fishman et al (2011) and that inactivity was costing Australia $13.8 billion, traffic congestion a further $13 billion and car trips another $9.6 billion in air, water and noise pollution (Australian Bicycle Council 2011).

By increasing peoples physical activity, cycling can help to reduce pressure on health services. Globally, physical inactivity is estimated to cause two million deaths each year, representing between 10 and 16% of cases of breast cancer, colon cancers, and diabetes, and over 20% of heart disease cases (World Health Organisation: Information sheet on physical activity, http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/media/en/gsfs_pa.pdf). The scene in Australia is similar, with approximately 16,000 deaths each year attributable to physical inactivity (Medibank Private (October 2008) The cost of physical inactivity). In 2007-08, 72% of Australians aged 15 years and over were classified as sedentary or having low exercise levels. Of these, just under half (49%) recorded no or very little exercise in the previous two weeks (sedentary exercise level) and 51% recorded a low level of exercise. Inactivity and obesity are linked, and in 2007/08 one quarter, or 600,000, of all Australian children aged 5-17 years were overweight or obese (Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009): Australian Social Trend – Children who are overweight or obese Cat. no 4102.0). This figure is even higher among adults – up to 61% are overweight or obese (Australian Bureau of Statistics: National Health Survey: Summary of Results 2007-08 Cat. No 4364). As well as helping to address overweight and obesity, regular physical activity can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some forms of cancer. It can also improve mental wellbeing by reducing feelings of stress, anxiety and depression. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Australia‟s Health 2006, AIHW Catalogue AUS73). The latter is particularly pertinent to the Katoomba region where higher levels of mental illness have been noted. (Treadwell 2010)

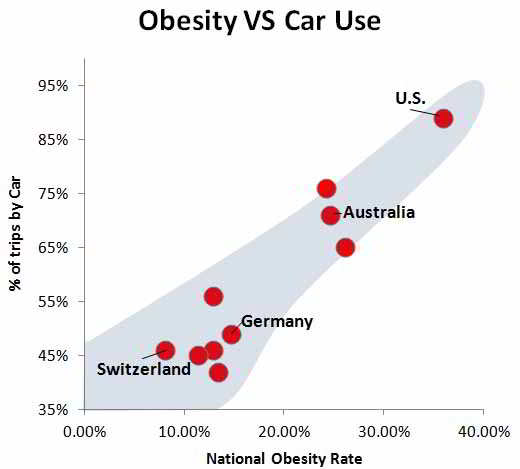

The health and environmental effects of reliance on car travel are linked (Swinburn et al 2011). Apart from the physical effects from inactivity, death and injury, and respiratory conditions linked to air pollution, there are a range of well documented effects on mental health and general wellbeing. Road traffic noise annoyance, traffic congestion and long commuting times contribute to stress, depression and anxiety, as do the opportunity costs of the time taken getting from one place to another (Dratva et al 2010; Ogilvie et al 2007; Frumkin 2002).

Policies that are likely to be most effective in mitigating the effects of road transport on climate change are also likely to be effective in addressing the range of impacts on physical and mental health (Woodcock et al 2009; Macmillan 2010; Haines et al 2007). Moreover, changing the built environment to encourage active transport options is known to reach population groups less likely to participate in leisure time physical activity (Fishman et al 2011). Investing in infrastructure that changes the built environment to make cycling and walking to every-day destinations like work and school convenient and safe has been shown to offset the health costs of sedentary lifestyles and to be more effective than individual behavioural interventions (Macmillan 2012, p. 33-34). There is evidence that such investment also provides a wide range of direct and indirect environmental, social, amenity and economic benefits (Gotschi 2011; Mackie 2010; Wu et al 2011; Turner et al 2011; Cycle to Work Alliance 2011; Guo & Gandavarapu 2010). A recent health impact assessment that investigated policies to reduce vehicle miles travelled in Oregon (Perdue et al 2012) similarly found that the most effective policies – limiting sprawl, increasing connectivity, and creating infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists - had a consistent association with health benefits, particularly increased physical activity and decreased air pollution.

Although there are many ways to be physically active, walking and cycling are among the most practical and effective, particularly for inactive and overweight people (Sevick, et al. 2000; Pucher and Beuhler 2010; Bassett, et al. 2011). The U.S. Center for Disease Control's Healthy People 2020 program includes specific objectives to increase walking and cycling (www.healthypeople.gov, PAF 10 and PAF 11). Residents of more multi-modal communities exercise more and are less likely to be overweight than in automobile-oriented communities (Ewing, Schieber and Zegeer 2003; Frank 2004). Analysis of 11,041 high-school students in 154 U.S. communities found that their odds of being overweight or obese decreased if they lived in more walkable communities (Slater, et al. 2013). Increased walking appears to reduce long-term cognitive decline and dementia (Erickson, et al. 2010).